Company Reportedly Resisted Following Safety Requirements, Leading to Death

Stowe zipline. Credit: Stowe Mountain Resort

Scott Lewis was an experienced zipline operator, having worked at the Stowe Zip Tour Adventure in Vermont for years.

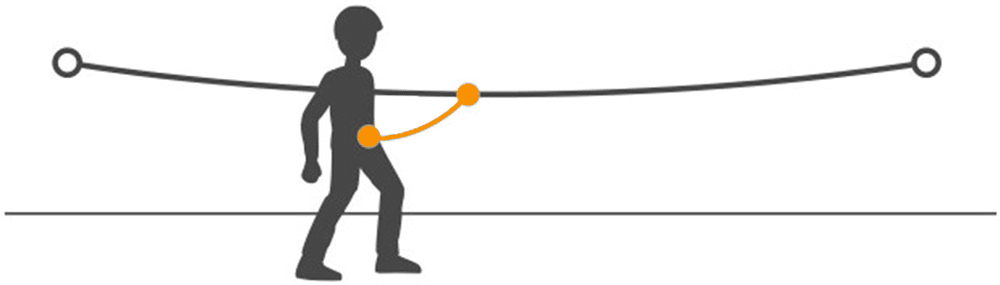

On September 23, 2021, just after 3 pm, according to press reports, Mr. Lewis was zipping down the line at up to 132 kph (82 mph), on his way to meet a group of guests. At the bottom of the zipline, he hit the spring brake at the end of the cable, and the lanyard (a short safety attachment rope) that he was using failed.

Mr. Lewis, 53, was detached from the zipline and thrown into the concrete anchor of the zip cable. He was found with his helmet off and his harness ripped. CPR was unsuccessful in resuscitating him.

The operator of the zipline, Stowe Mountain Resort, based in Vermont USA, was cited by the state’s health and safety agency for multiple serious safety violations. Stowe was fined $27,306.

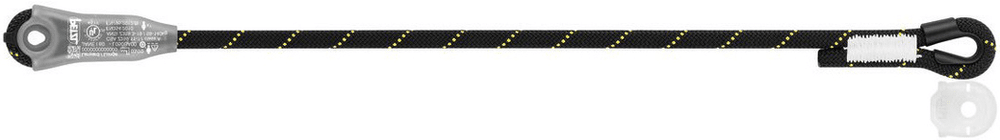

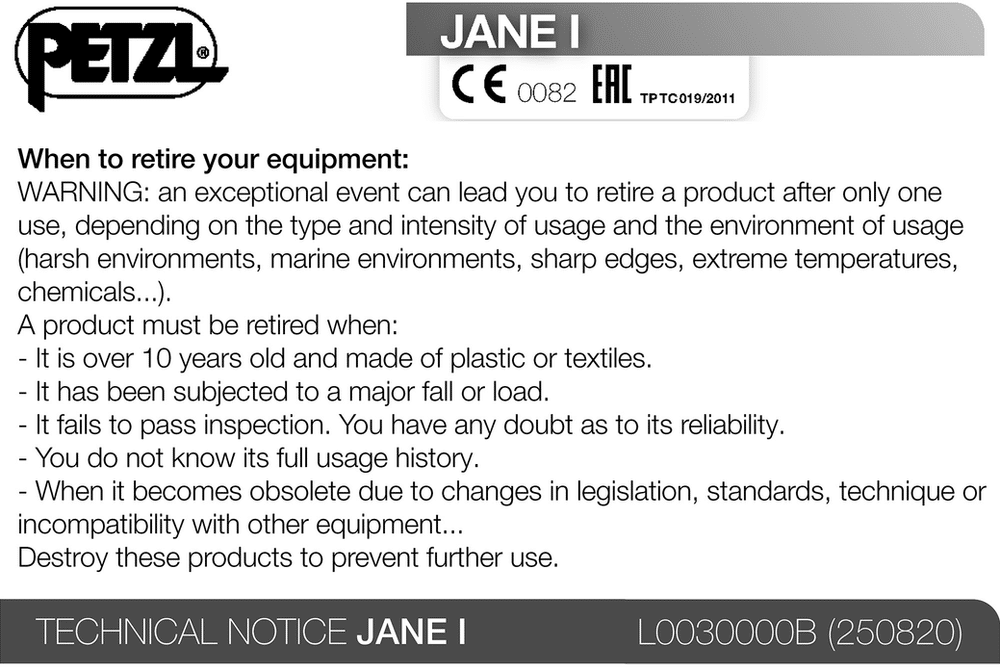

The installer of the ZipTour zipline, Terra-Nova LLC of Utah, required that the lanyard, a piece of personal protective equipment (PPE) designed to protect a person from falling, be replaced annually. (Petzl’s JANE-I lanyard was specifically described in the agency report.) But Stowe did not do this required annual replacement.

The health and safety agency, Vermont Occupational Safety and Health Administration (VOSHA), investigated the incident. They found problems that went beyond failing to replace safety equipment as required.

VOSHA found that Stowe had failed to properly inspect and replace safety equipment, and failed to provide appropriate training to its employees.

Specifically, VOSHA cited Stowe (a unit of Vail Resorts, operating under the corporate name VR US Holdings II, LLC) for

-

Failure to annually retire safety lanyards, as required

-

Inspections of safety equipment not providing for appropriate retirement of PPE

-

Not documenting inspections of critical PPE

-

Not individually identifying PPE so it could be tracked

-

Not being able to provide documentation or required certification of safety training

These failures, VOSHA said, led to the preventable death of Mr. Lewis.

The JANE-I lanyard. Credit: Petzl

Violations in Detail

VOSHA’s report described one citation, with two separate items.

Citation 1, Item 1

VOSHA cited Stowe for a Serious Violation of Section 223 of Vermont's statues on labor, dealing with occupational safety and health duties. VOSHA found that Stowe "did not furnish employment and a place of employment which were free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious harm to employees; in that the employer failed to abide by the instructions from Terra-Nova LLC of Utah in retiring annually the primary attachment lanyard, known as the jane lanyard."

VOSHA stated that “the employer, despite being notified, directly by the manufacturer of the ZipTour ride, failed to consider the jane lanyard an annual replacement item and replace these critical pieces of safety equipment prior to the start of the 2021 season.”

The investigation by VOSHA found that “the main rider attachment lanyard, which was four years old and which had nearly three full seasons of use (termed by the ride manufacturer as intensive use) was found to have failed and caused the rider to become separated from the ride.”

Lanyard (orange) in action. Credit: Petzl

Citation 1, Item 2

VOSHA also found three deficiencies with Stowe’s training of employees, and policies regarding use, maintenance, and inspections of critical components of personal protective equipment:

A. “Inspections of critical components of PPE did not provide for appropriate retirement of the PPE as specified by the ride manufacturer.

B. Annual inspections of critical PPE was [sic] not documented nor was the PPE individually identified in a way that would allow tracking of these components.

C. The employer was not able to provide documentation of specific training or certification (as required by the manufacturer of the ride) of training to perform these critical inspections both monthly and annually as they were required to do.”

VOSHA described this as a Serious Violation of federal occupational and health standard 1910.132, Personal Protective Equipment, specifically 1910.132(f)(1), “The employer shall provide training to each employee who is required by this section to use PPE.”

This regulation requires that employees shall be trained to know at least when PPE is necessary; what PPE is necessary; how to properly don, doff, adjust, and wear PPE; the limitations of the PPE; and the proper care, maintenance, useful life and disposal of the PPE.

VOSHA also separately cited a violation of section 1910.132(f)(1)(v) of that regulation, requiring training on “the proper care, maintenance, useful life and disposal of the PPE.”

Zipline at Stowe

In their analysis, VOSHA found that “training records provided by the employer did not indicate the ZipTour guide employees had been trained on the useful life and disposal of the jane lanyard. ZipTour employees use the Stowe ZipTour Employee Equipment Inspection Log for daily inspections. Under the section labeled textile components, employees must inspect for the following: burns, glazing, deformation, cuts, frays, pulled threads/critical stitches, marks, stains, stiff spots, soft spots, core shots, excessive fuzziness, burrs, chemical exposure, excessive wear, obsolescence.”

During an employee interview with a Ride Supervisor, the employee said that they did not know “what the word obsolescence means.”

The employee also stated they were a Company Certified Inspector. However, VOSHA noted that “the manufacturer states to become a Company Certified Inspector, one must demonstrate to them (Terra-Nova) that they have a complete understanding of the ride system prior to performing the inspection.”

VOSHA noted that “There are no records indicating [the employee] was trained or certified directly by Terra-Nova to become a Company Certified Inspector.”

VOSHA found that the organization provided no documentation of training in inspection procedures for the employee who was generally charged with conducting annual inspections of critical PPE including lanyards, helmets and harnesses.

The last documented annual inspection of the PPE was in May 2019, conducted by Terra-Nova. At that time Terra-Nova reportedly found the lanyard “showed glazing and excessive fuzziness.”

The lanyard at the time of the incident, VOSHA found, was four years old and had glazing throughout.

Lanyard in action. Credit: Vuedici/Petzl

An Additional Issue: Knot In Lanyard

In the course of operations, Stowe personnel reportedly used a Grigri belay device attached to the safety lanyard.

In the original citation VOSHA issued on March 21, 2022, the agency noted that the lanyards did not have a minimum breaking strength of 5000 pounds (22.2 kN) after an overhand knot was tied next to the Grigri belay device, for the purpose of stopping the belay device from creeping down the lanyard.

VOSHA described this as a Serious Violation of federal occupational and health standard 1910.140, Personal fall protection systems, specifically 1910.140(c)(4), "Lanyards and vertical lifelines must have a minimum breaking strength of 5,000 pounds (22.2 kN)."

In addition, VOSHA noted that the employer did not have a competent or qualified person inspect the knot to determine whether or how much the knot weakened the lanyard.

VOSHA described this as a Serious Violation of the same standard, specifically section 1910.140(c)(6), “A competent person or qualified person must inspect each knot in a lanyard or vertical lifeline to ensure that it meets the requirements of paragraphs (c)(4) and (5) of this section before any employee uses the lanyard or lifeline.”

After negotiation with a law firm representing Stowe, this language was removed from the final citation. Language was instead placed in the listing of abatement measures, stating that “The employer shall also obtain from the manufacturer of the Petzl Jane lanyard certification that it approves the use of a slip knot on the Jane at the point that it exits the non-load side of the belay device, prior to putting the Jane lanyards back in service.”

What did VOSHA reference, in explaining why it raised the issue of the knot in the lanyard?

In its report, the agency stated, “It is generally accepted industry knowledge that tying a knot will weaken the breaking strength of the lanyard.”

VOSHA also referenced American National Standards Institute/American Society of Safety Professionals standard ANSI/ASSP Z359.12 (Connecting Components for Personal Fall Arrest Systems) 3.2.1. 1.2.1, stating “knots are not permitted in lanyards.”

ANSI/ASSP Fall Arrest Connecting Components standards

VOSHA also noted that, according to Petzl’s tech tip Making a Y-lanyard with a knotted JANE or PROGRESS ADJUST I lanyard, an overhand style knot can reduce the strength on the lanyard leg from 22 kN to 14kN.

In its March 25 Violation Worksheet, VOSHA concluded: “One employee was killed after using a Petzl jane lanyard that failed and did not meet the minimum breaking strength of 5,000 pounds (22.2 kN) after an overhand knot with a loop in the tag end was tied, causing the employee to be separated from the ride.”

Resistance to Following Safety Requirements

News reports said that the Vail Resorts, which operates Stowe, “had not only failed to retire the lanyards every year, but resisted doing so.”

VOSHA’s report noted that in February 2017, Terra-Nova LLC of Utah, the manufacturer of the ZipTour ride, provided an update to its Operations and Maintenance Manual stating, “the Jane lanyard has a maximum lifespan of 1 year with heavy use,” on the condition that it passes “all daily, monthly and yearly inspections.”

On June 7 2017, the Director of Operations Training and Risk Management at Vail Resorts responded to Terra-Nova LLC of Utah, saying “The term heavy use is undefinable. We are not willing to accept your change to another companies [sic] equipment retirement criteria without a clear safety alert or service bulletin per ASTM. We will continue to follow the Petzl retirement criteria that is clear and definitive.”

The day after, the President of Terra-Nova LLC responded to Vail Resorts’ Director of Operations Training and Risk Management, saying, “It is our opinion that this is Petzl’s requirement.” The President continued, writing that the Petzl documentation “states the component should be rejected if ‘the component has had more than 6 months of intensive use, 12 months of normal use, 10 years of occasional use.’ TN feels that a season of use on the ZipTour is equivalent to 6 months of intensive use. Terra Nova will not alter this requirement.”

On October 24 2019, Terra-Nova put out an industry-wide Manufacturer Supplemental Bulletin/Safety Alert regarding the jane lanyard, stating “The main attachment lanyard is an annual replacement item, on the condition that they pass ALL daily and monthly inspections.”

That same day, the Director of Operations Training and Risk Management at Vail Resorts responded by email. (VOSHA noted that the Director of Operations Training and Risk Management had years of experience in the adventure course industry and the requirements of the industry, and extensive knowledge of the ANSI/PRCA 1.0-.3-2014 (Ropes Challenge Course Installation, Operation And Training) standards, as he had previously submitted comments to the committee drafting the standards.)

That response stated:

I have a few questions and clarifications to this safety alert.

1. Did you really intend to have this as a safety alert as this would mean all zip-tours world wide would need to shut down until all lanyards greater than a year old are replaced. There are Two [sic] other forms of notifications that might have been more appropriate.

2. Can you please provide the communication from Petzl (the manufacturer of the primary connection lanyard) stating that they are changing their inspection and retirement criteria’s [sic].

3. How did your hazard analysis identify annually as the most appropriate timeline? Some of your tours run as short as three months with little use and some of your tours in warm climates run year round with high through put.

4. There is not a clear description of the issue / incident that led to the change and need for a safety alert. (This is required per ASTM.

while I understand your need to produce service bulletin’s [sic] it should be done with thorough hazard analysis and real risk mitigation and not from a perspective of easy vertical integration that benefits the manufacturers [sic] gear sales.

Terra-Nova replied, reiterating their conclusion that the use of the equipment was of the “intensive type.” Terra-Nova refused to delete the safety alert.

Petzl’s retirement specification for JANE-I lanyard

Less than two years after Vail Resort’s Director of Operations Training and Risk Management questioned the Safety Alert, Scott Lewis plunged to his death as his safety lanyard, glazed and worn, and well past its retirement date, broke in two.

Vail Resorts had purchased 50 JANE lanyards in 2019. They cost $26.00 each.

Consequences

Stowe Mountain Resorts is a unit of global operator Vail Resorts, a multinational corporation that calls itself "the leading global mountain resort operator," with 37 destination mountain resorts and regional ski areas in the USA, Canada, and Australia.

Vail reported $1,907,940,000 in net revenue for fiscal year 2021.

Following the incident, Vail released a statement, saying “Safety is our highest priority, and Stowe Resort and the entire Vail Resorts family extend our deepest sympathy and support to this employee’s family and friends.”

The zipline is currently closed; no timeline for re-opening has been announced.

Because Mr. Lewis’ death occurred at the workplace during work hours, the incident is covered under worker’s compensation insurance, and no lawsuit against the company is possible.

Could VOSHA pursue criminal charges? No intent to do so has been announced.

VOSHA stated, “When an employer is charged with a willful violation of a VOSHA standard and that alleged violation results in the death of an employee, VOSHA may ask the Vermont Attorney General’s office to seek criminal prosecution of the employer.”

VOSHA notes, however, that “These are difficult cases to prove and few cases reach court and convictions are rare. However, should an employer be convicted, he or she could face a fine of up to $250,000 individually and/or a jail term of up to six months. A corporation could receive a fine of as much as $500,000.”

The header of the citation (redacted)

Conclusions

Tragedies like Mr. Lewis’ untimely death remind us of both what we already know, when it comes to good risk management—and also our responsibility to work to improve our efforts, to help ensure incidents like this do not happen again.

Not every incident can be prevented. But, according to VOSHA, this tragedy could have been.

Individuals reviewing the circumstances of this incident may point out failures regarding several risk domains, or areas where risks reside:

-

Equipment. Gear and supplies should be selected, sourced, used, inspected, maintained, repaired, stored and retired according to industry standards and manufacturer specifications.

-

Staff. Personnel should have the knowledge, skills, abilities and values required to do their job well. They should be trained, supervised and supported as needed to meet performance expectations.

-

Documentation. Evidence of appropriate practices—from equipment management to staff training and supervision, and more—should be durably recorded.

-

Culture. A positive culture of safety, which truly values safety as a core organizational priority, must be established and maintained.

But we know these.

Will a $27,000 fine impel a multi-billion-dollar corporation to shift its safety culture? Or will that simply be considered the cost of doing business, and no substantive changes will result? The future holds the answer.

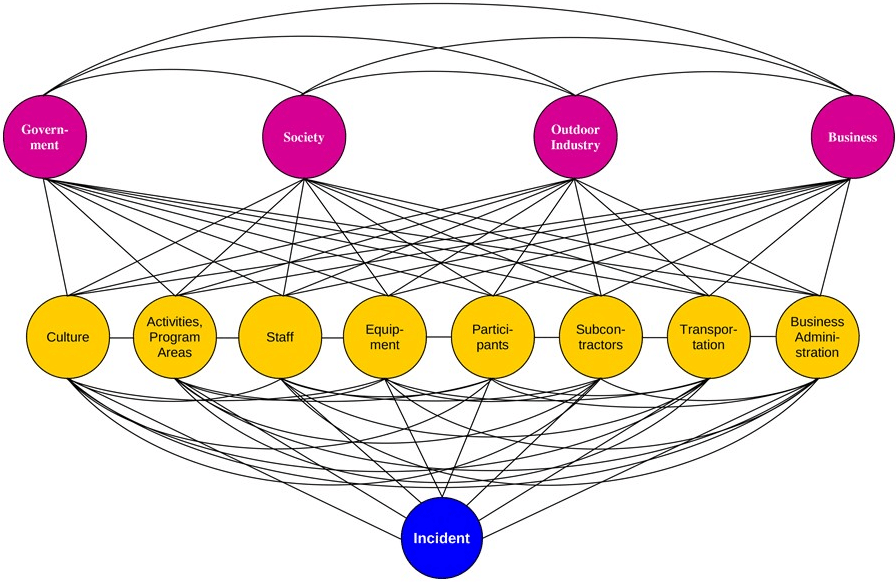

A Theoretical Model of Incident Prevention

We can keep in mind that major incidents in the outdoor industry often spring from multiple risks, emerging from various risk domains, which combine in unpredictable ways to lead to an incident.

In addition to risk domains involving equipment, staff, documentation and safety culture, risks also reside in areas having to do with activities and program areas, participants, subcontractors (providers), transportation, and business administration.

Indirectly, risk factors in government (such as the ability to craft and enforce meaningful safety regulations), society (in its tolerance of risk), the outdoor industry (with respect to setting standards), and the corporate world (with holding a sense of civic duty) influence safety outcomes as well.

Outdoor, travel, experiential, and adventure programs that seek to responsibly and effectively manage risk should work to reduce the risks in these 12 risk domains (which may apply to their organization), to be as low as is reasonably practicable, and not to exceed a socially acceptable level.

Risk Domains

And outdoor and experiential programs are most effective when they, in addition, employ risk management instruments, or tools, that can reduce risks across multiple or all risk domains.

(Guidance on how to do this is available in a number of places, including an outdoor safety textbook and a Risk Management for Outdoor Programs training.)

By committing to understand the science of how incidents come to pass—and how they may be prevented—and by working to employ best practices and industry standards in risk management for experiential, adventure and similar programs, we can help ensure that the tragedy of preventable death, such as befell Scott Lewis, does not occur again.