[This article was originally published in Merbau, the journal of the Wilderness and Austere Medicine Society of Malaysia (WAMS), in the 2/2023 issue, under the title Introduction to Risk Management in the Wilderness. WAMS provides training, resources and advocacy to advance the field of wilderness medicine in Malaysia. Access the journal and learn more about WAMS here.]

Leong Jim Meng was asleep at a campground on a forested hillside in Batang Kali, Malaysia, when he was awoken by a loud bang. The noise “sounded like an explosion,” he said. He felt the earth move.

A massive landslide swept into the campground, located some 50 km north of Kuala Lumpur in the picturesque Genting Highlands, a popular outdoor recreation area known for its waterfalls and scenic tropical landscapes.

The landslide poured 450,000 cubic meters of earth on the unsuspecting outdoor recreationalists. Ninety-two people were hit. The sudden earthflow, which occurred shortly after 2 am on December 16, 2022, buried sleeping campers, tents and cars in a mass of mud and debris up to eight meters deep.

Rescue efforts, using over 700 emergency workers employing excavators and search dogs, went on for nine days. Thirty-one persons, including 13 children, died.

How can tragedies like the Batang Kali incident be prevented? How can the impact of potential incidents in the outdoors—whether in a rural campsite or deep in the wilderness—be minimized?

These are the questions that the field of wilderness risk management seeks to answer.

Wilderness Risk Management, Defined

Wilderness risk management can occur in remote natural areas, such as Borneo’s 750-square-kilometer Kinabalu Park, or regional parks and rural settings closer to emergency services. “Outdoor safety” and “wilderness risk management” are sometimes used interchangeably.

What do we mean by “risk?” We can define risk as the possibility of undesirable loss.

Risk management can be understood to mean the systematic, intentional and ongoing process of reducing risk so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP). Since what is reasonable and what is practicable vary in different socioeconomic circumstances, we can also consider the process of risk management to mean reducing risk to a socially acceptable level.

Four General Approaches to Risk Management

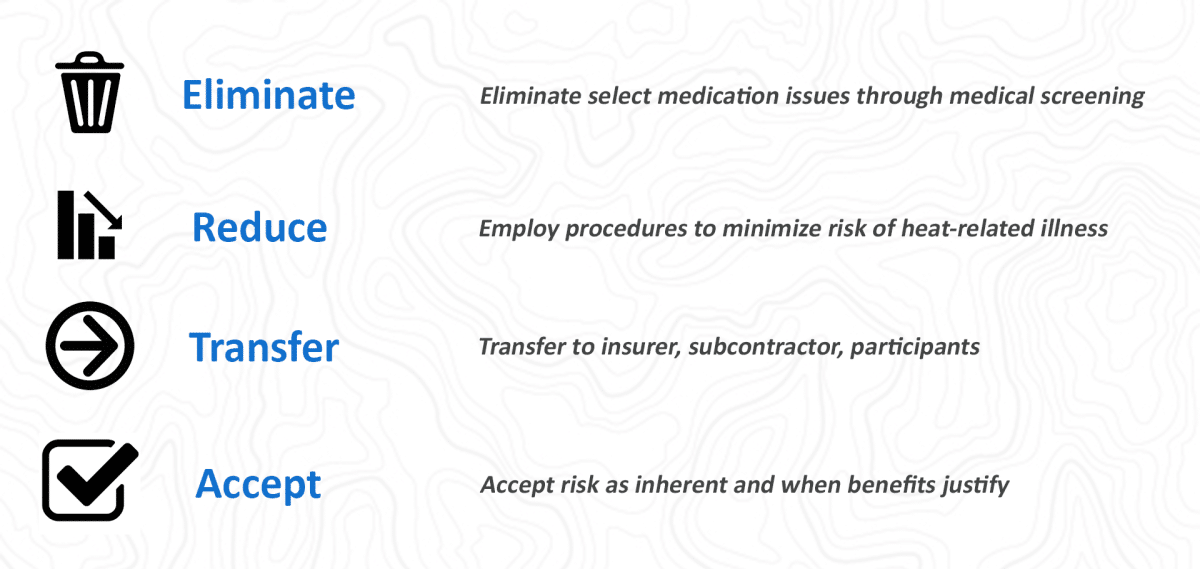

Risk can be managed—in outdoor settings, or anywhere else—using four general approaches: eliminate, reduce, transfer or accept risk.

Risk can be eliminated by, for example, not engaging in certain activities. The risk of a participant on a remote outdoor trip dying of internal bleeding due to clot-inhibiting medication use can be eliminated by implementing a medical screening process where applicants for backcountry expeditions who are currently taking anticoagulant medications such as warfarin are medically rejected from participation.

Risk reduction is where the majority of outdoor risk management actions occur. Instituting operating procedures based on the results of risk assessments is an example; for instance, requiring a certain level of wilderness medical training for varying levels of remoteness of outdoor trips. Risk of landslides and avalanches can be reduced by minimizing time spent in terrain where those phenomena may occur.

Risk transfer can be accomplished by transferring risk to insurance companies in exchange for payment of an insurance premium, to participants through signing of liability release forms, and to providers (subcontractors), who agree to take responsibility for certain activities such as providing the white-water rafting component of a multi-element expedition organized by a tour operator.

Outdoor experiences come with certain risks that cannot be eliminated without changing the fundamental character of the event. Program operators and participants must accept a certain level of risk that comes with the experience.

Theoretical Models of Outdoor Risk Management

Why do incidents occur? And, as a corollary, how might they be prevented, or their harms mitigated?

To answer these questions, it’s helpful to have a theoretical model exploring the elements that can lead toward an incident occurring.

Academicians in the field of risk management—across industries, from nuclear power generation to aviation and healthcare—have come up with numerous such models. And new frameworks of causation are continually being developed.

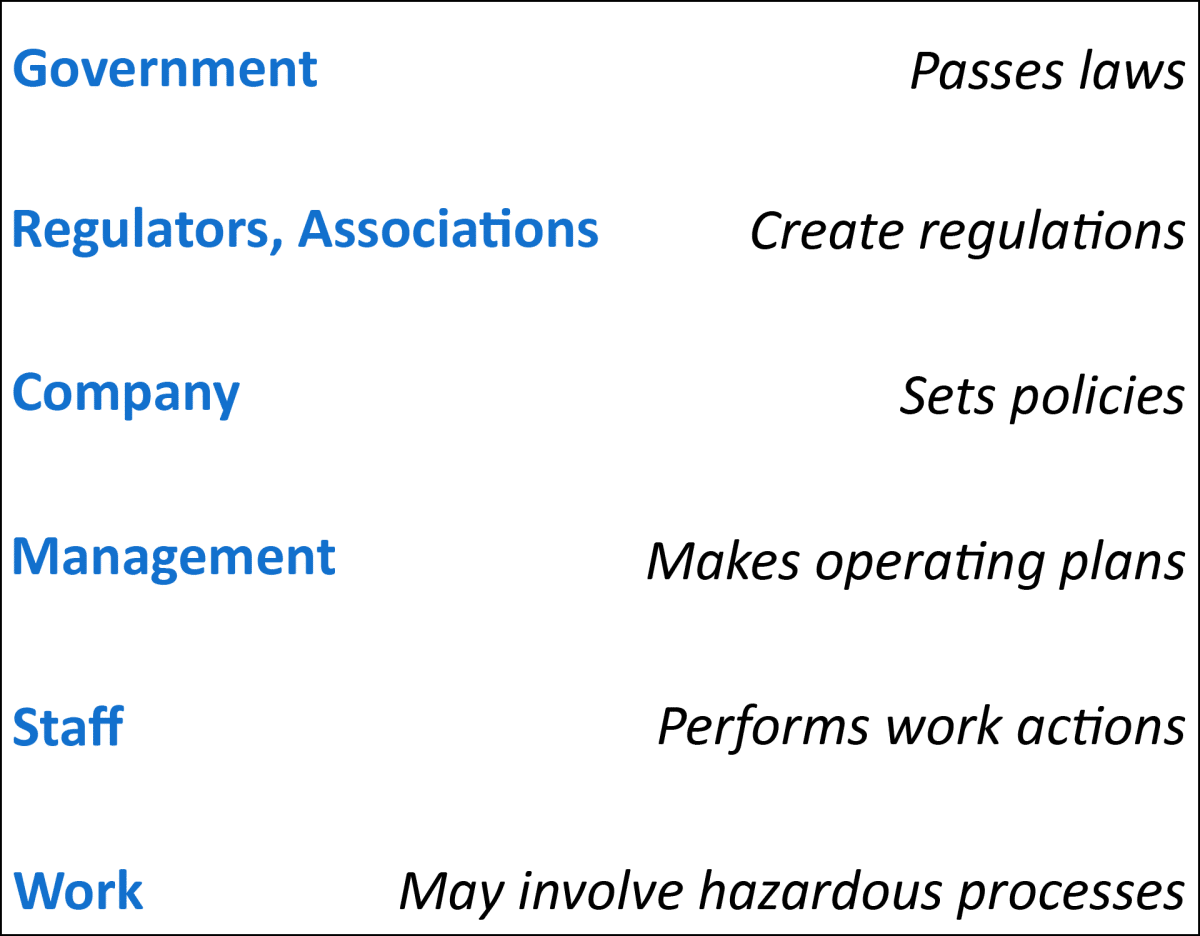

Perhaps the most well-known model is AcciMap, developed by a Danish researcher, Jens Rasmussen, who worked in the field of nuclear safety. Rasmussen stated that in order to reduce the probability and impact of incidents, safety measures must be taken throughout multiple levels of the larger societal environment. These levels include government, industry-specific associations, company management, and individual front-line workers.

Risk Domains Model

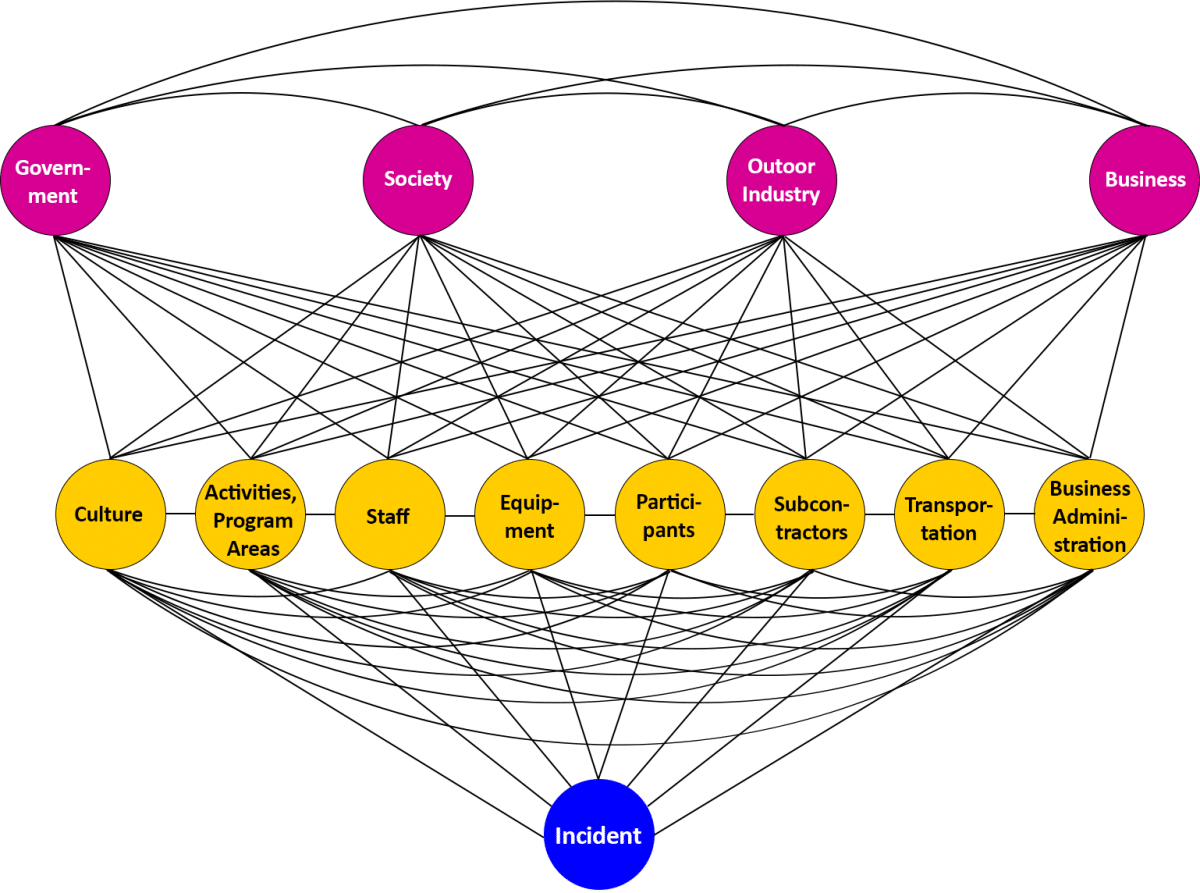

Another model has been developed specifically for use in outdoor, adventure, wilderness, travel and experiential education settings. This framework, the Risk Domains model, sees risks within a set of eight direct risk domains (in yellow, below) contributing to the occurrence of an incident. The Risk Domains model also illustrates four underlying risk domains (in fuchsia, below), where risks in these areas may indirectly contribute to an incident’s occurrence. Risks in all direct and underlying risk domains are connected, and combine in unpredictable ways to lead to a mishap taking place.

Risk domains, in this model, are places where risks reside.

In the eight direct risk domains, Culture refers to issues of safety culture—the beliefs and values held by individuals and groups, which drive safety-related behavior.

Activities and Program Areas addresses risks specific to activities—like hikes in a tropical environment, where heat-related illness is a risk—and program areas, like tall mountain peaks, which present risk of altitude sickness.

Staff refers to risks brought on by activity leaders or administrative personnel, such as failing to follow safety procedures.

Equipment indicates risks due to gear, vehicles, supplies and facilities that may be poorly maintained, inappropriate, malfunction, or otherwise contribute to an incident.

Participants refers to individuals such as customers partaking in an organized outdoor experience, who may, for instance, be insufficiently trained or supervised.

Subcontractors refers to vendors or providers who may cut safety corners or in other ways cause safety problems.

Transportation refers to risks associated with travel, for example the risk of motor vehicle accidents while traveling to a trailhead or boat launch site.

Business administration risks include embezzlement, fraud, theft of confidential information, and other administrative-related risks.

Leaders of wilderness-based and other outdoor programs should conduct a risk assessment to determine what risks their organization may reasonably expect to encounter in each of these risk domains. Leaders should then incorporate management strategies for each of those risks into operating procedures, training plans, staff handbooks, and elsewhere, so that those identified risks are kept as low as reasonably practicable.

Underlying Risk Domains

Underlying risks, which indirectly can make an incident more or less likely to occur, include the domains of government, society, the outdoor industry, and businesses.

When governments enact and enforce safety laws and regulations, incidents are likely to be less frequent and severe.

When society has a low risk tolerance, pressure is put on organizations and government entities to institute effective safety measures.

When associations and other bodies in the outdoor industry create training systems (such as in wilderness medicine or kayaking skills) and standards-based accreditation schemes for organizations, safety outcomes may improve.

When large corporations exhibit a sense of civic responsibility and don’t systematically degrade the ability of government to establish and enforce safety rules, severe incidents throughout society are less likely to occur.

Risk Management Instruments

The Risk Domains model also describes several broad-based tools, or ‘instruments,’ which can be used to reduce risks across multiple or all risk domains.

These risk management instruments are:

- Risk Transfer. Shift of risk to insurers, participants and providers/vendors.

- Incident Management. Written and practiced emergency response plans.

- Incident Reporting. Systematic recording and analysis of safety incidents.

- Incident Reviews. Formalized evaluation of major mishaps.

- Risk Management Committee. A group with external representatives providing safety guidance.

- Medical Screening. Assessment of staff and participant medical suitability.

- Risk Management Reviews. Periodic, proactive safety audits.

- Media Relations. Training for successfully liaising with news media.

- Documentation. Durably recording what should be done and what has been done.

- Accreditation. External recognition that industry practices are met.

- Seeing Systems. Incorporating systems thinking, such as resilience engineering, in safety.

Theoretical models of incident causation and prevention can be used by wilderness-based and outdoor programs in many ways. A framework such as the Risk Domains model can be incorporated into risk assessments, procedure development, safety audits, incident reviews, and development of risk management plan and safety management system documents.

The successful application of a model such as Risk Domains requires organizational leaders to have a deep understanding of best practices regarding managing risks in each of the risk domains, and skill in applying all relevant risk management instruments.

Seeing Systems

The models illustrated above are constructed with an understanding that major incidents typically occur when a number of risks from various direct and underlying risk domains come together in impossible-to-predict ways to lead to an incident.

For instance, causal factors that may have influenced the Batang Kali landslide have been proposed to include the hillside above the campsite being built of road construction fill, which became waterlogged; increased rainfall due to climate change; licensing and zoning issues, and immunity provisions in the Local Government Act 1976 reducing incentives for effective safety management.

(An official investigative report regarding the incident, which as of July 2023 had not yet become widely publicly available, may provide a more definitive explanation of causal factors.)

The concept that incident causation comes from multiple factors interacting in ways that cannot be precisely anticipated springs from complex socio-technical systems theory.

Under this theory, which states that we cannot know in advance or control all the factors that might lead to an incident, organizations seeking to manage risk are most effective when they build resilient, multi-layered risk management systems.

This means incorporating a certain amount of redundancy in safety infrastructure, so if one element fails, a catastrophic consequence can still be prevented.

For example, a wilderness expedition might be staffed by two capable trip leaders, so one can continue on if the other is incapacitated.

It also means building in sufficient capacity to withstand surges in demand, or a sudden decrease in supply. If an expected water source on a wilderness trek is dry, or unexpected temperature extremes are encountered, the group should have alternate options for maintaining hydration and thermoregulation.

Older models of incident causation, such as the Domino Model and the Swiss Cheese Model, employ a linear approach to understanding why mishaps occur. This linear model is considered outdated, and less effective than a systems-informed way of understanding why incidents happen.

Risk Domains in Focus: Government

Most outdoor risk management work happens at the managerial level. Despite the popular misconception that when a wilderness incident occurs, it’s primarily due to the inappropriate actions of the activity leader closest to the incident, research suggests this is not the case. Instead, administrative steps—within outdoor providers, outdoor sector associations, and government bodies—are the predominant influence as to whether incidents occur or not, and if they do, the magnitude of the loss incurred.

Let’s take a closer look at how actions in the underlying risk domain of Government could have influenced the landslide tragedy in Batang Kali.

Following the incident, the Malaysian government said that all campsites nationwide located by rivers and hillsides would be closed for a week to conduct risk assessments of those high-risk sites.

The government halted outdoor recreation activities in Batang Kali.

All picnic and camping spots across Selangor, the state in which the town of Batang Kali is located, were temporarily closed.

Motion-detecting soil sensors were installed near the incident site, to alert authorities to possible future landslides.

The Municipal Council of Hulu Selangor, the district within Selangor state which contains Batang Kali, noted that a specific license for campsites did not exist, and called for a policy regulating campsites to be enacted.

A government official announced that Selangor would introduce new regulations around campsite activities.

Although these actions came too late for the victims of the Batang Kali landslide, these are the kinds of steps—risk assessments, safety regulations, and an effective licensing scheme—that can have a powerful influence on preventing future outdoor tragedies.

In addition, the campsite operator reportedly was permitted to operate without a business license, and in violation of the conditions of an environmental impact assessment report. Observers said that effective enforcement of existing regulatory requirements, and accountability for government authorities who fail to act, are important elements in helping prevent further disasters.

A group of teachers, students and staff from a Kuala Lumpur primary school were on an unofficial camping trip at the campsite when the landslide occurred. Eleven members of the group perished. No matter how well trained the trip organizer might have been in wilderness first aid, camping hygiene, or bushcraft survival skills, no medical or safety certification could have prepared them to prevail against underlying forces—such as a flawed and ill-enforced permitting process–beyond their knowledge or control.

Standards and Laws

Another important element in wilderness risk management has to do with voluntary good practice standards, and legal requirements regarding outdoor safety.

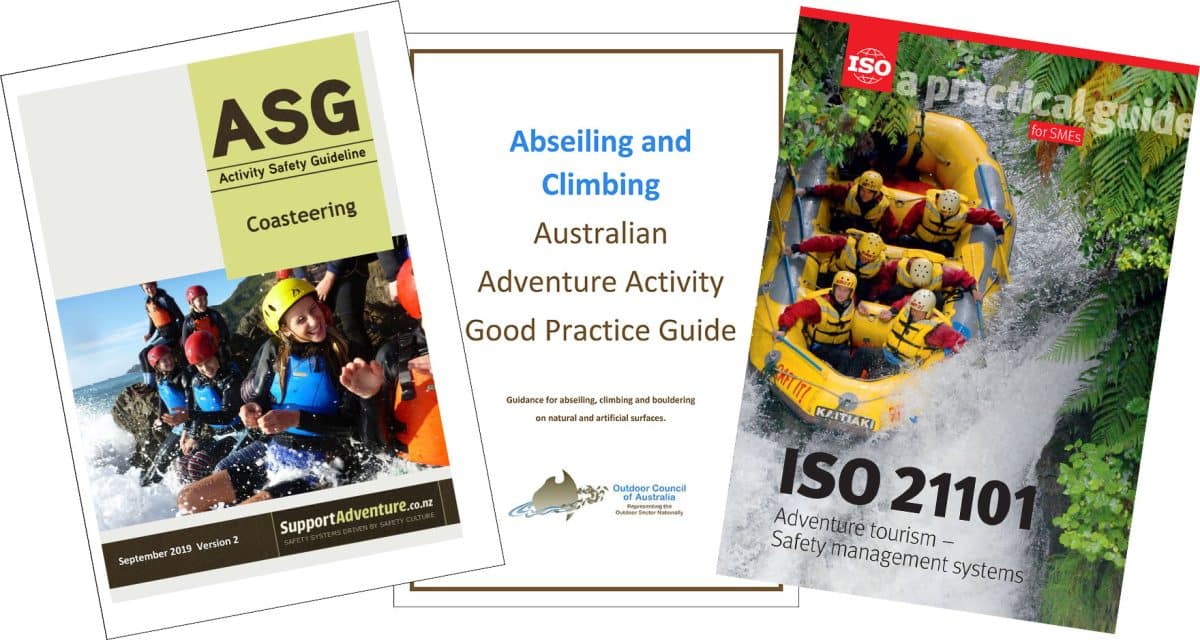

A variety of voluntary standards addressing outdoor and adventure activity safety exist. The New Zealand outdoor adventure sector publishes Activity Safety Guidelines and Good Practice Guides through their ‘supportadventure’ resource, and the Australian Adventure Activity Standard and associated Good Practice Guides also offer detailed activity-specific guidance.

A handful of consensus standards, such as ISO 21101 on safety management systems for adventure providers, also offer useful guidance.

And some countries, such as the UK, Switzerland and New Zealand, have comprehensive safety regulations regarding outdoor adventure activities.

Although similar standards and legislation are rare in Southeast Asia, the global trend is for increasing adoption of such guidelines and laws. Singapore, which has a deep commitment to outdoor adventure activities, and the economic resources to invest in regulating them, is a regional leader in this regard.

Wilderness Risk Management and Wilderness Medicine

Outdoor safety and wilderness medicine—and its adjacent disciplines, emergency medicine and disaster medicine—intersect in multiple ways.

Wilderness medical training is an essential part of wilderness safety. Certificated wilderness medical training courses with an evidence-based and well-developed curriculum (including those whose curricula meet the scopes of practice established by the Wilderness Medicine Education Collaborative, such as the courses offered by the Wilderness & Austere Medicine Society Malaysia) help outdoor leaders prevent incidents, intervene early, and respond effectively to emergencies.

Medical screening of prospective participants and staff helps ensure that those on an expedition are medically well-suited for the activities and environments anticipated.

And emergency medical care providers who are well-prepared to handle environmental emergencies, delayed or prolonged transports, and mass casualty situations help ensure the best possible outcomes for injuries and illnesses suffered in outdoor settings.

This involves all aspects of the emergency medical services system—from search and rescue teams and ambulance services to governmental disaster response coordinators and hospitals.

A high-functioning EMS system has developed multiple layers of interoperating emergency response plans, has conducted small and large-scale disaster response drills, and has developed procedures and delivered training so that emergency care providers can operate successfully under stressful crisis conditions.

Prior to the landslide, a comprehensive disaster drill with table-top, clinical and field components was held in the Genting Highlands region involving the fire and rescue department, Royal Malaysian Police, civil defense department, Ministry of Health, national disaster management agency, medical care providers and others.

The benefits of this advance preparation was demonstrated well in the Batang Kali mass casualty incident. In the middle of the night, medical providers from nearby Hospital Selayang responded promptly to the emergency, and search and rescue teams handled extrication and public communications.

Hospital Selayang contacted Kuala Lumpur Hospital, which immediately activated its Disaster Plan. Activating the Disaster Plan prepared hospital staff for an influx of patients, established expanded disaster victim treatment areas, and provided resources for communicating with families and providing psychological first aid.

A third hospital, Tunku Azizah Hospital, specializing in pediatric care, went on Yellow Alert, and emptied their resuscitation area in preparation for handling a large number of injured children. The hospitals jointly decided which type of patients would be sent to which hospital.

Trends in Risk Management of Led Outdoor Activities

Recent decades have brought significant advancement in well-developed outdoor safety resources accessible by wilderness, experiential and adventure professionals.

Access to theoretical models of incident prevention useful to outdoor leaders is more available in textbooks, online resources and trainings.

Scientific research on decision-making under stress, adventure risk management standards, and high-quality certificated outdoor risk management training are better developed and more widely available.

Expert specialists are now available to conduct risk management reviews of outdoor organizations, and provide incident reviews following major mishaps.

What will the future bring?

Further development of good practice guidelines and outdoor safety regulation, discussed above, is expected.

Recognition of psychological stress injury as just as important to address as physical illness and injury is growing.

One survivor of the Batang Kali landslide described how she still struggles with traumatic memories of the incident. Her close friend was found dead while hugging one of his three dogs. She was trapped in her tent when dirt and trees from the landslide covered the tent. Bystanders cut open the tent, lifted off the trees, and were able to pull her out. “Since the incident, I have not taken the initiative to go hiking,” she said. “I never expected to be affected in this way.”

As a consequence of the increasing awareness of psychological stress injury, written resources and training on psychological risk management for outdoor leaders are undergoing rapid development.

And considerations of equity and inclusion in outdoor experiences are gaining increased and much-needed attention. This involves fostering a welcoming and psychologically safe environment for all persons in the out-of-doors, regardless of race, religion, skin color, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, national origin, disability status, or other characteristics.

Conclusion

The wilderness carries inherent risk—altitude sickness atop Mt. Kinabalu, twisted ankles from rocky trails, and more. Yet when these risks are well managed, the powerful benefits of outdoor experiences—including refreshment of the spirit, development of life skills, and physical health and mental well-being—can greatly outweigh the hazards of travel in the out-of-doors.

Good risk management in outdoor settings includes applying a systems-based incident prevention model to planning, conducting, and continuously evaluating organized outdoor activities.

The development and application of good practice guidelines developed by the outdoor industry, and thoughtfully developed and effectively enforced regulatory structures, can help support good safety outcomes in outdoor adventures, and make positive outdoor experiences more accessible to more people.

Good wilderness safety practices complement high-quality wilderness and austere medicine trainings in making experiences in remote and outdoor settings safer and more fulfilling.

On the morning of December 16, 2022, trained and diligent rescuers responded to the scene of the Batang Kali landslide. The skills and hard work of hundreds of responders led to most of the landslide victims being saved, and the rescuers deserve recognition for their hard-won success.

And the incident also illuminates elements of outdoor risk management that will benefit from continued advancement, to help reduce the likelihood that such a tragedy will occur again.