An effort is underway in the UK to systematically collect incident reports across the outdoor adventure sector, analyze the data, and disseminate reports that can enhance the safety and quality of outdoor adventure activities across the UK.

The project is a collaboration between the University of Highlands and Islands—North, West & Hebrides; the Adventure Activities Industry Advisory Committee, and the Institute for Outdoor Learning, with funding from the Scottish government.

Understanding what incidents are occurring, and with what frequency and severity, along with gathering information about potential contributing factors, can help improve safety outcomes. The ambitious project in the UK has the potential to achieve this aim.

Gathering information from across the outdoor adventure sector, and disseminating the results of analysis of the data, however, is a real challenge.

The first phase of the UK project involved developing and testing an incident-reporting system. A report on this recently completed phase identified a number of considerations that can influence the project’s success.

A primary concern centered around the legal ramifications of distributing incident data. This recently became a significant issue in Canada, where an incident report submitted to the country’s mountain guide association was obtained during a lawsuit against that organization, leading the association to terminate its incident report collection system.

Workload

Many outdoor and adventure programs struggle to gather and process incident reports on their own activities, let alone input the data into a third-party aggregator system. Some outdoor education and recreation operations don’t systematically collect incident data at all. Others do, but reports pile up on a desk or in a folder without thoughtful analysis or follow-up. The topic of workload has also been an issue in now-defunct outdoor incident reporting schemes in the USA and Canada.

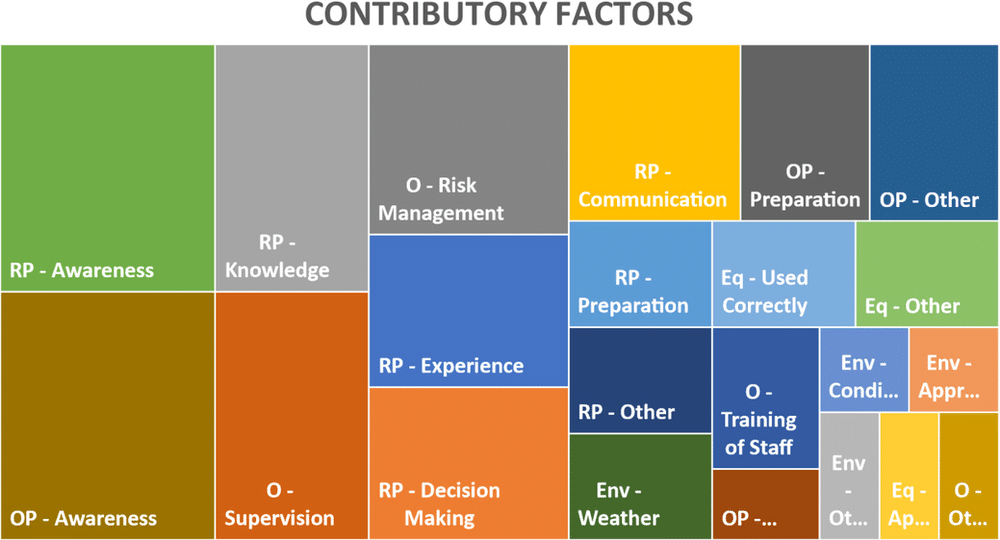

Conformance with Other Incident Reporting Systems

A variety of activity-specific associations in the larger UK adventurous activities sector, such as those involved with mountaineering, paddlesports, and caving, already operate incident reporting schemes. Harmonizing data fields across all incident report forms requires technical expertise and a sustained commitment to collaboration.

The UK report noted the “disjointed” approach in the sector to improving risk management practices based on incident analysis; the report noted this was pointed out in the UK government’s investigation of a fatal SUP incident in Wales in 2021.

Data Consistency and Quality

Different organizations have varying approaches to incident reporting, which may influence the integrity of aggregated data.

For example, some organizations might have the activity leader fill out an incident report, with the benefit of first-hand knowledge, awareness of potential contributing factors, and expert understanding of industry standards. Another organization might have an administrative assistant or senior manager input the data, who would not have the knowledge and perspective of the outdoor professional directly involved.

Similarly, different organizations may have varying approaches to subjective topics, such as what constitutes a near-miss, what ranks as a ‘severe’ incident, or which are possible contributing factors.

Outdoor Incident Reporting Scheme Challenges Around the World

In 1992, the Association for Experiential Education initiated a project to collect and analyze incident data from outdoor programs worldwide. With reporting voluntary and funding scarce, the project ended in 2008. A replacement international incident database was proposed, but did not materialize.

Results of a study of incident reporting by outdoor programs affiliated with the Association for Outdoor Recreation and Education published in 2019 showed widespread interest in participating in a national incident reporting database. However, obstacles to actually doing so included:

- Lack of staff time

- Lack of value compared to the labor involved

- Organizational policy against sharing data externally

- Insufficient training in reporting and analysis

- “Fear of retaliation”

- Liability concerns

When incident reporting schemes span cultures and geographies, additional complexities emerge. If incident reports come from different data sets, difficulties arise from comparing incident data across databases.

Some entities may record participant contact hours, while others use a participant-day metric. Some organisations may wish to distinguish between staff, participants, observers, and chaperones; others may not. Harmonizing terminology and definitions of activities—such as distinguishing between river tracing, canyoning, shower climbing, ghyll scrambling and kloofing—must be addressed. Determining which types of activities are eligible for reporting—for example, environmental education, residential programming, wilderness therapy, or orienteering—should be resolved.

None of these issues are insurmountable, however, with sufficient application of willing partners, managerial acumen and financial resources.

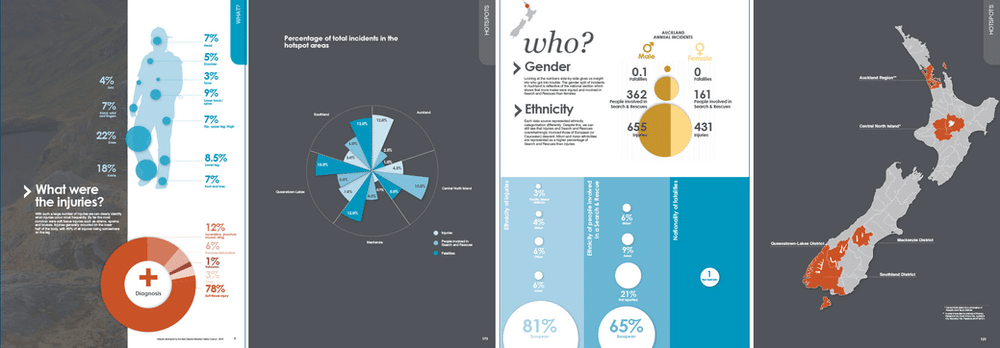

An Outdoor Incident Data Collection Success Story: New Zealand

In the early 2000s, the New Zealand Mountain Safety Council, Outdoors New Zealand, Education Outdoors New Zealand and the New Zealand Ministry of Education collaborated on a “National Incident Database Project” to create a standard method for collecting and analysing New Zealand outdoor education and recreation incident data. The National Incident Database (NID) project, whose online database system went live in 2004, solicited information from across the outdoor sector, including outdoor centres/providers, national organizations, recreational clubs, schools, tertiary education organizations, outdoor event organizers, adventure tourism providers and ski field operators. Reports were issued between 2009 and 2012 before the initiative became inactive.

Incident analysis was conducted in some outdoor sector segments such as outdoor education and the equestrian sector. However, NID organizers noted that most outdoor recreation sectors in New Zealand “are highly fragmented with little centralised capacity to run their own sector incident or participation information systems.”

Various other efforts, such as work by the Ministry of Education to support voluntary incident reporting from the country’s Education Outside the Classroom (EOTC) sector, were made, with limited results.

NID organizers wryly noted “any incident recording in the wider outdoor recreation sector appears to be highly variable on the rare occasions it occurs.”

In the New Zealand scheme, the New Zealand Mountain Safety Council collects data from the national governments’ Accident Compensation Corporation, which pays for accident-related medical care; the New Zealand Search and Rescue Council, which incorporates data from NZ Police; the National Coronial Information System; the Department of Conservation, which manages about 30 percent of New Zealand’s land area, and other sources. The most recent report, from 2016, offers 180 pages of detailed analysis and insights.

Although the data sources do not always collect incident details at a level of specificity that might be most useful to the outdoor and adventure sector, the relatively wide variety of sources, the use of reporting entities with the expertise and funding to sustainably provide high-quality data, and the enormous amount of data submitted—1,147,000 participants and 65,000 incidents over 11 years, including 100 fatalities—mitigate this limitation.

A Path Forward for the UK and Beyond

Professionals in outdoor recreation, adventure travel, outdoor education and related fields value learning from the stories of others. And they are eager to benefit from the continuous improvement of industry good practice standards that comes from systematic review of safety incidents.

Incident report collection and evaluation remains fragmented across activities, geographies, and report-collecting entities. However, the initiative launched in the UK is promising, and a welcome addition to the decades of efforts to understand how incidents in the outdoor and adventure sector occur, and how they might be minimized or prevented.

The UK project can be informed by previous efforts to share insights gained from large-scale incident analysis. And the work of others to develop similar incident reporting and learning schemes can take inspiration from the leadership shown by those in the UK seeking to use incident data to advance the effectiveness and sustainability of outdoor adventurous activities.