The Five-Million-Dollar Missing Comma

A delivery driver for a dairy company in Maine, USA was chatting with a person in a grocery store stockroom, and mentioned he wasn’t provided overtime pay, despite working up to 16 hours a day.

The stockroom person said this was probably illegal.

Delivery drivers then sued the dairy for back pay.

The law said that workers are not eligible for overtime pay if their work involves “marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution” of perishable foods. [Emphasis added]

The dairy claimed this means that no overtime pay is owed to both 1) people who pack perishable foods, and 2) people—like milk truck drivers—involved in distribution of perishable foods.

The drivers disagreed. They said the language means that people who pack perishable foods (for reasons like shipment or distribution) aren’t overtime-eligible, but since they distribute food, they are.

Without a comma between “packing for shipment” and “or distribution,” the court in 2017 ruled in favor of the delivery drivers.

For the lack of a comma, the dairy company paid USD 5 million.

Technical Writing: Bringing Clarity to the Written Word

Most organizations wish to avoid spending millions on legal fees, followed by making a 5 million dollar back-wages payment.

One way to prevent these kinds of costly problems is to have clear and unambiguous writing in the first place.

This is where the practice of technical writing comes in.

Technical writing is a specific discipline of professional writing characterized by discipline, control, conciseness, consistent formatting and design, taxonomic crispness, and accuracy.

It’s a skill which improves with training and practice.

Technical writing is used in contexts like legal writing, medical documentation, legislative/regulatory language, operating instructions for dangerous equipment, and computer application documentation.

It can also be used by outdoor, travel and adventure programs in the creation of safety policies and procedures.

Features and Benefits of Technical Writing

Technical writing is writing characterized by:

- Precision,

- Accuracy, and

- Clear, logical organization.

Its use is generally not required by law.

Appropriate application of technical writing, however, can increase the likelihood of experiencing good safety outcomes.

Good safety outcomes, in turn, can improve customer satisfaction, organizational reputation, protection from legal liability, and business sustainability.

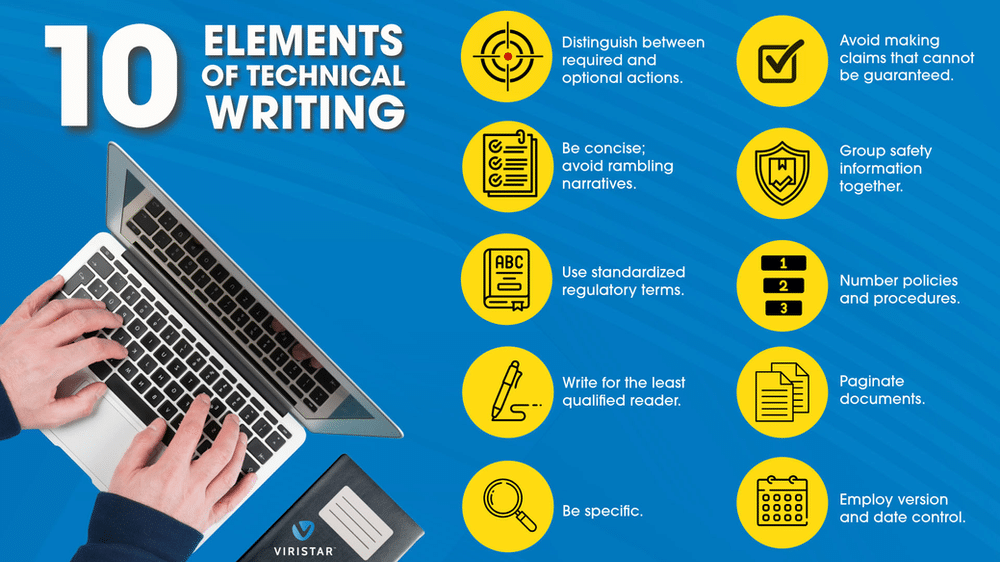

Technical Writing: 10 Good Practice Tips

Ten ways in which persons writing safety documentation can employ good technical writing practices are described below. These ideas fall into three general categories—precision, accuracy, and clear, logical organization.

Precision

-

Distinguish between required and optional actions.

-

Be concise; avoid rambling narratives.

-

Use standardized regulatory terms.

-

Write for the least-qualified reader.

-

Be specific.

Accuracy

6. Avoid making claims that cannot be guaranteed.

Organization

7. Group safety information together.

8. Number policies and procedures.

9. Paginate documents.

10. Employ version and date control.

Precision

1. Distinguish between required and optional actions.

This can be accomplished by using:

- “Must” or “shall” to refer to mandatory actions

- “Should” to refer to actions that are recommended, but not obligatory

- “May” to actions that can be taken at one’s discretion

One way some organizations describe these categories is in “policy, procedure, guideline” format.

- Policies are rules for which compliance is compulsory.

- Procedures are recommended good practices, which ought to be followed in most cases, but which are acceptable to not follow if a superior alternative is clearly present

- Guidelines are optional actions, such as suggestions, tips, hints, and ideas, where following or not following them are both accepted.

Whatever system an organization uses, the documentation should describe the meaning of the terms used in the chosen hierarchy of level of conformance obligation.

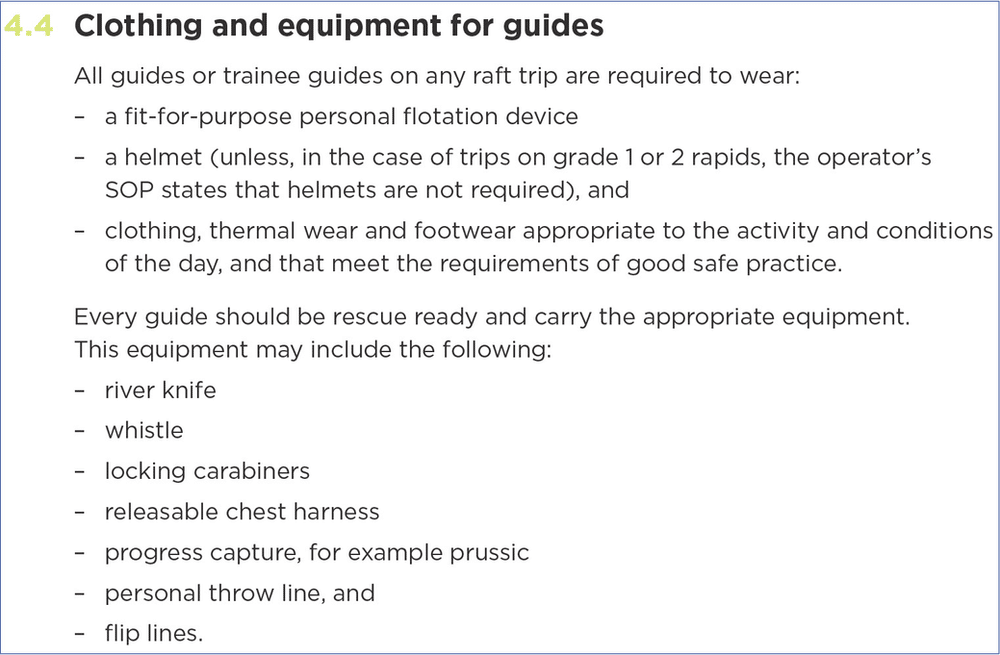

The following excerpt from the whitewater rafting Good Practice Guideline document from WorkSafe, New Zealand’s health and safety regulator, makes a clear distinction between what is required, and what a whitewater raft guide should, but is not obligated, to do.

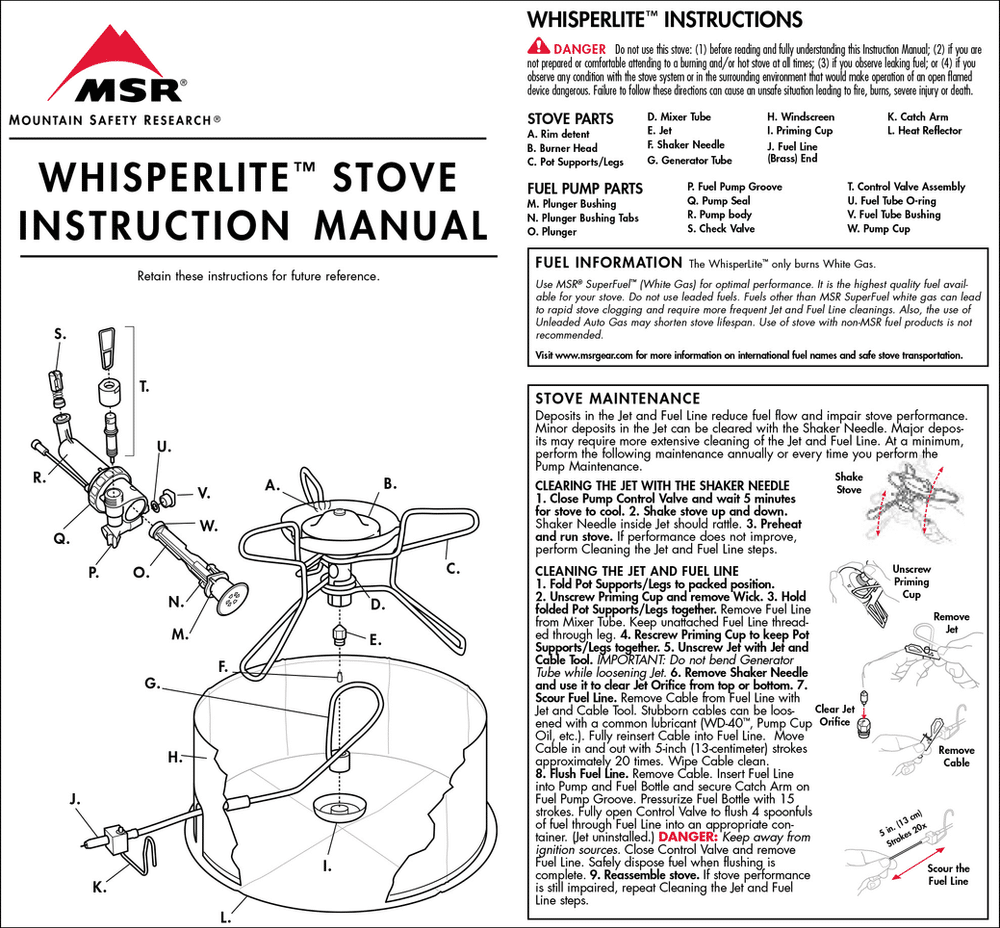

When writing safety procedure documentation, it can be useful to use as a reference manufacturer requirements and recommendations. For technical installations such as challenge courses, safety procedure documents can use installer and designer/engineer notes and directions.

For instance, camp stove operating procedures should follow manufacturer guidance, such as the below.

2. Be concise; avoid rambling narratives.

Instead of writing long-winded, meandering prose, write concise, focused introductions followed by enumerated or bulleted lists.

For example, the “Hazardous Conditions” chapter of the risk management manual of an outdoor education organization in the western USA contained a section on tornadoes, composed of a focused narrative description followed by a list of procedures:

Tornadoes

Tornadoes are nature’s most violent storms. They come from powerful thunderstorms and appear as rotating, funnel-shaped clouds. Tornado winds can reach 480 kilometers per hour. They cause damage when they touch down on the ground—an area 1.6 km wide and 80 km long. Every state in the USA is at some risk, but fortunately for us, locations west of the Rockies are much less likely to experience tornadoes. Tornadoes can form any time of the year, but the season runs from March to August. The ability to predict tornadoes is limited; usually there will be at least a few minutes’ warning. The most important thing to do is TAKE SHELTER when a tornado is nearby.

Procedures

- Basecamp/frontcountry:

- Listen to a radio for weather updates. If a tornado is coming, seek shelter. An underground shelter is best, such as a basement or storm shelter. Failing that, find an inside room or hallway or closet on the first floor away from windows.

- If the group is in a vehicle, attempt to take shelter in a nearby building.

- Backcountry: lie flat in a ditch or ravine. Lie face down and cover your head with your hands.

- After a tornado, watch for broken glass and downed power lines. Beware of unsteady trees or other natural objects.

3. Use standardized regulatory terms.

Regulatory terms include policy, procedure, guideline, protocol, recommendation, and standard.

These words should not be used interchangeably. Any regulatory term used should be defined, ideally in a definitions section or glossary.

One environmental education organization’s safety manual used the following terms, without distinguishing between them:

- protocol

- procedure

- directive

- principle

- best practice

- things to be aware of

- steps you can take

- tip

- guideline

Usage of a two-part (must/should) or three-part (must/should/may) model, such as the “policy-procedure-guideline” approach described above, would aid in clarity.

4. Write for the least-qualified reader.

This means that written material should provide a sufficiently high level of clarity, reading ease, specificity and detail so as to reasonably ensure that the least-qualified potential reader receives reasonably unambiguous direction.

Factors that may influence reading comprehension include:

- Fluency in language used in writing (for example, if a second or third language)

- Experience with the activities, locations, and participant types involved

- Level of academic attainment (for example, first aid procedures referring to blood pH may be unclear to those without secondary level (high school) biology/chemistry education)

- Anticipated stress level of reader (e.g. in emergency situations)

Some organizations with personnel from a wide diversity of backgrounds, for example, write critical safety directions so that they can be read and understood by persons at a grade 3 reading level, i.e. a level of reading ability associated with eight-year-olds.

5. Be specific.

This is a common issue in safety procedures for adventure tourism, experiential education, educational travel and similar organizations.

Examples of over-vague safety guidance that Viristar has encountered in the course of conducting incident reviews, risk management audits, and reviewing and updating safety documents of clients include:

“Be aware of your surroundings”

“Be very aware of male/female interactions between participants”

“Walk cautiously”

For one client, Viristar recommended replacing the non-specific language:

“Be sure to stay hydrated and shaded”

with the following:

Procedure

Students should be encouraged to stay hydrated. In order to accomplish this, instructors should:

- Warn students about the risk of dehydration within the first 12 hours of the program (see “Initial Safety Briefing” document);

- Complete a gear check to ensure each student has sufficient water bottle capacity;

- Encourage students to drink whenever they are thirsty;

- Schedule adequate hydration breaks, and

- Pack powdered drink mixes to add to halogenated water to increase drinkability.

Guideline

Instructors may engage students in games involving water-drinking to encourage appropriate (but not excessive) water consumption.

Similarly, Viristar recommended one client replace the procedural language

“Be careful around animals”

with language that illustrates what this means, for example:

“Tapirs are generally shy and will typically avoid conflict with humans, but tapirs and all wild animals can be unpredictable, and tapirs can deliver powerful bites. Be particularly careful around adults in breeding season or with their young. Avoid positioning where a tapir may feel cornered. Even animals that appear calm or ignore people can charge without warning. Never approach a wild tapir. If a tapir may be too close, back away slowly.”

It can be helpful to complete lists wherever possible, and avoid the use of “etc.” to indicate unspecified additional items.

Accuracy

6. Avoid making claims that cannot be guaranteed.

A Parent Handbook at a summer camp stated that “every camper is well attended-to at camp,” and implied campers will have a “safe experience.”

If there is a momentary lapse of staff attention, during which a camper is harmed, or if a camper is injured or otherwise does not have a “safe experience,” this can unnecessarily invite legal liability.

Organization

7. Group safety information together.

This refers to two practices:

- Organizing safety information in one (or very few) locations, for ease of access

- Separating safety information from other information, such as business administration details

Safety information in one or few locations

It can be helpful to organize risk management information in one or a small number of easy-to-access locations.

For example, a field activity leader manual should not have safety procedures scattered throughout other content. Instead, the manual could be organized into chapters, each covering a topic such as:

- Organization information (e.g. mission, history, services)

- Logistics (e.g. food, equipment, transportation)

- Program content (e.g. schedules, activities, client profiles)

- Safety

All relevant safety information that an activity leader might need should be in the manual, and not sprinkled among different forms, handbooks, risk assessment sheets, and so on.

If the manual is in paper form, sections could be identified by labeled tabs, and the ‘safety’ chapter could be printed on colored paper to stand out from other content.

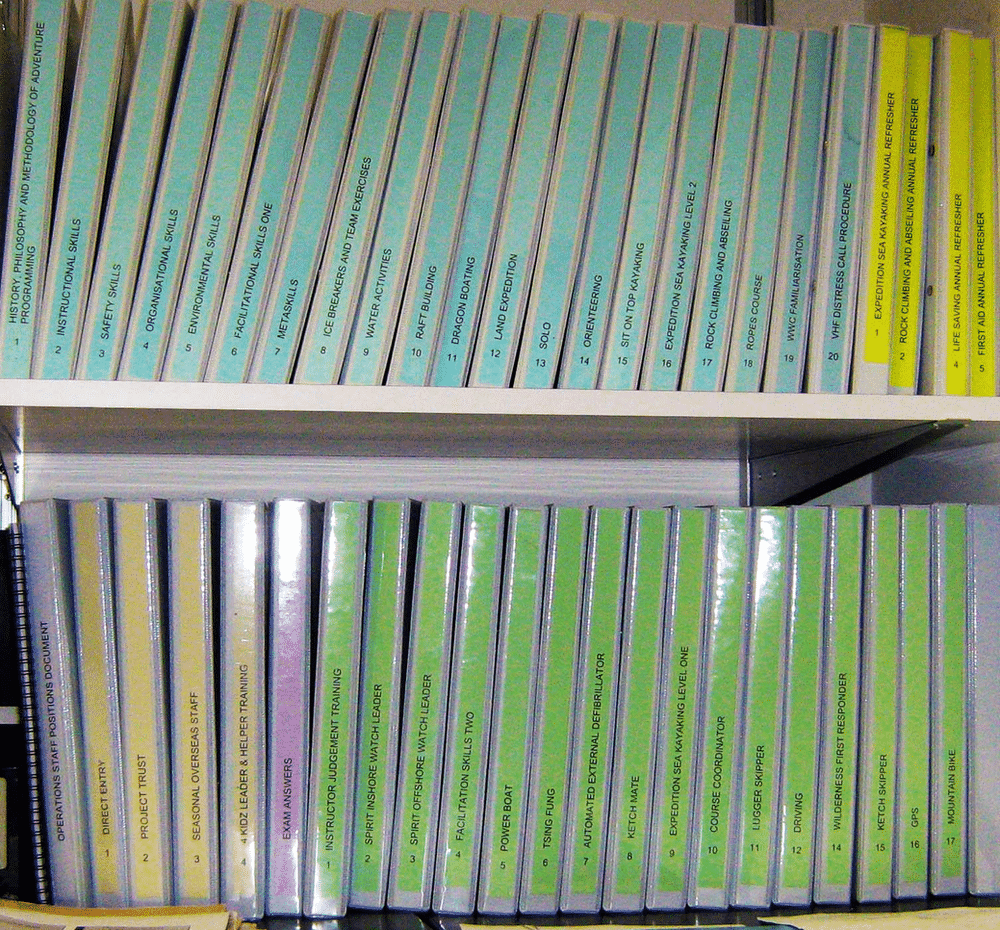

When Viristar requested review copies of safety documents for a youth education organization providing outdoor adventures and educational travel experiences for which Viristar was conducting a risk management review, the organization provided over 6,000 documents, including multiple similar versions of certain documents.

In an interview conducted during the safety review, one employee said, “it’s incredibly frustrating to have to sift through a million and one different places to get the information I need.” The employee continued, “It exists somewhere; you just have to find it…why do we not just have one handbook?”

An organization might have a limited set of safety documents, such as:

- A Risk Management Plan, or Safety Management System document, which describes the organization’s overall approach to safety, including topics like safety culture, how a sufficient number of qualified staff are employed, the system for recording and evaluating incidents, and a continuous quality improvement plan.

- An Emergency Response Plan for administrators, describing actions such as contacting emergency services; staff, current participants and potential participants; community stakeholders, and legal and insurance representatives, during an emergency, and arranging for long-term response in the months and years after a critical incident

- An Emergency Response Plan for field staff, describing first aid, search, and evacuation procedures, among others

- Standard Operating Procedures for field staff, describing how to conduct activities such as adventure, cultural, and travel activities according to good practice standards

- Other documents, particularly for larger institutions, such as safeguarding policy, periodic safety reports, risk assessments, and HR procedures.

Safety information segregated from other information

Risk management language should be separated from written content not associated with risk management.

For example, safety procedures should be not mixed in with background information, such as:

- program logistics

- customer service practices

- information on education, recreation, or other program outcomes

- descriptions of activity areas

- the history of the organization

- general features or benefits of certain activities

- the nature of participant demographics

The Field Risk Management Manual of one organization mixed safety guidance with other content in a section on hazardous organisms:

Predatory, Poisonous and Venomous Animals

We are aware that the places we travel are the homes of animals, and we are simply visitors. We always enter a wilderness area with respect and admiration. While we love to see animals in their habitat, in general, we try to avoid run-ins with animals that have the potential to harm us. In general, if an animal is not provoked, we will be safe; however, there are always exceptions. Know which animals are in an area you are visiting and know how to protect the group if you come close enough to see them. If you want to geek out on wildlife fatalities: [URL link to information].

8. Number policies and procedures.

Each important safety direction—whether called a “policy” and “procedure” or by other terms—should be assigned a unique serial number.

This assists with ease of reference and communication.

An example, for policies and procedures regarding harness use in an outdoor adventure program, follows.

Harnesses

Policies

[C-1.] Harnesses shall be used when belaying, technical climbing, abseiling, and during Tyrolean traverse activities, challenge course, and high initiatives.

[C-2.] Harnesses and knots shall be checked prior to each use by staff.

[C-3.] In circumstances where carabiner connections between the rope and harness are used, two carabiners, one of them locking, shall be used. (This policy applies when a person is being actively belayed with the rope while climbing or being lowered.)

[C-4.] When attaching a rope to a harness for belaying abseilers or attaching lobster claws to a harness, one locking steel carabiner will suffice.

Procedures

- Participants should be instructed in the proper use and care of the harness before any climbing or challenge course activity.

- A properly fitting harness should be used; it should not be able to slide over the hips, and leg loops should be snug but not restrictive (i.e. two fingers can be inserted between harness and leg).

- Each time a harness is removed and retied, it should be checked by a staff member. The harness check should include a visual check of the buckle, safety knots, and tightness of the harness. If a hands-on check of the harness is necessary, the staff should ask for permission before touching.

9. Paginate documents.

Placing a page number on each page of a document assists with locating and referencing specific content.

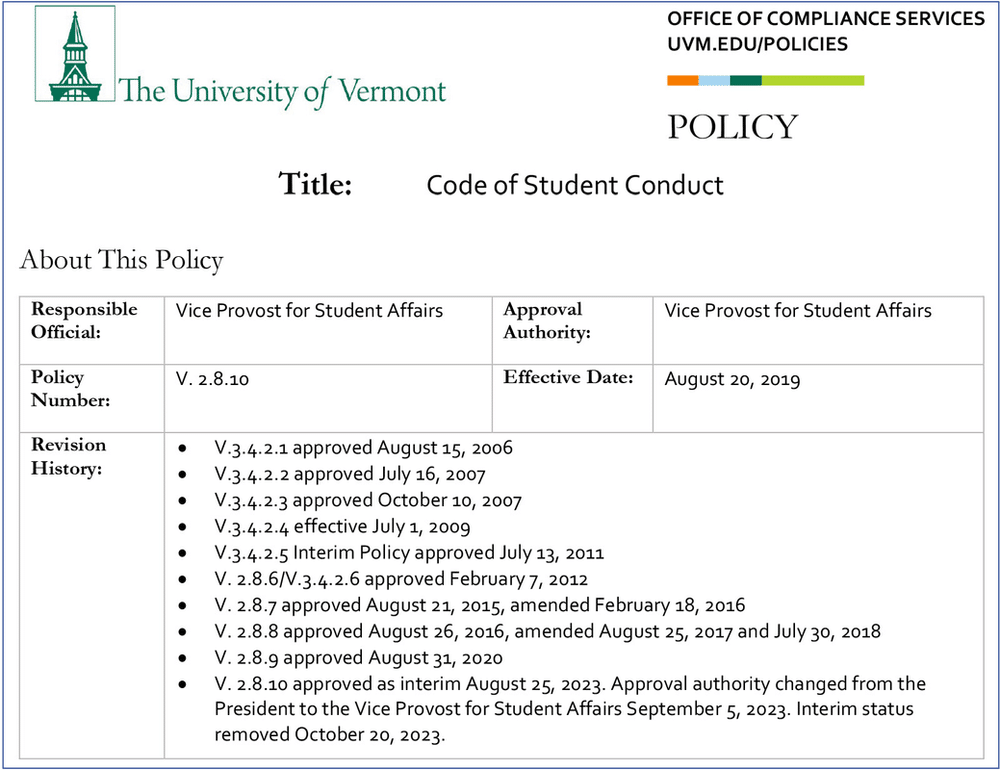

10. Employ version and date control.

Documents should indicate what version they are (e.g. third edition or version 2.0).

Documents should also indicate the dates when they were last revised.

This can be done in the footer of a document, or in a revision history/effective date document section, as in the university conduct policy excerpt below.

Good Writing Practice

Part of technical writing is simply using good professional writing practice, which applies to both technical and non-technical communications.

Good writing practice involves coherence, clarity, and control. These characteristics can be shown by, for example, expressing complete thoughts, preferentially using active voice, and writing for the appropriate audience.

Coherence: Express Complete Thoughts

Coherence involves language where complete thoughts are expressed, and content components logically interconnect and make sense overall.

For example, an instructor handbook for an experiential program, in its transportation procedures, said:

Visual inspection of all vehicles before departure.

This does not specify if the inspection is required or optional, who should do it, or how it should be done.

A coherent procedure that expresses a complete thought might be:

Immediately before each trip, the vehicle operator shall complete a visual inspection of the vehicle to be driven, as specified on the Pre-Drive Vehicle Inspection form, and shall record the results on that form.

Another organization, which conducted outdoor education activities, listed in their emergency procedures:

Every parent is called.

Clarifying who calls parents (presumably only parents of children involved in the emergency) would strengthen this procedure.

Clarity: Use Active Voice Over Passive Voice

Use of active voice provides a more clear, concise and direct style of communicating.

The following language was used in the safety documentation of an experiential education program:

Course reports need to be completed on time.

An alternative in active voice is:

Instructors shall complete course reports on time.

Control: Write for the Appropriate Audience

The instructor manual for an educational travel program included language apparently intended for program participants (rather than instructors), including the following two excerpts:

Sleeping outside of tents allowed with instructor approval only.

The majority of your time will be with your host family.

These might be better placed in the participant handbook. The first item could also be kept in the instructor manual, with wording such as:

Instructors must approve in advance any sleeping outside of tents.

Finally, good writing practice includes a robust editorial process. Safety documents should undergo proofreading and editorial review. They should be reviewed by end-users (such as adventure guides, outdoor instructors, camp counselors, program managers, and the like). Feedback from user testing should be incorporated into the final version of the documents.

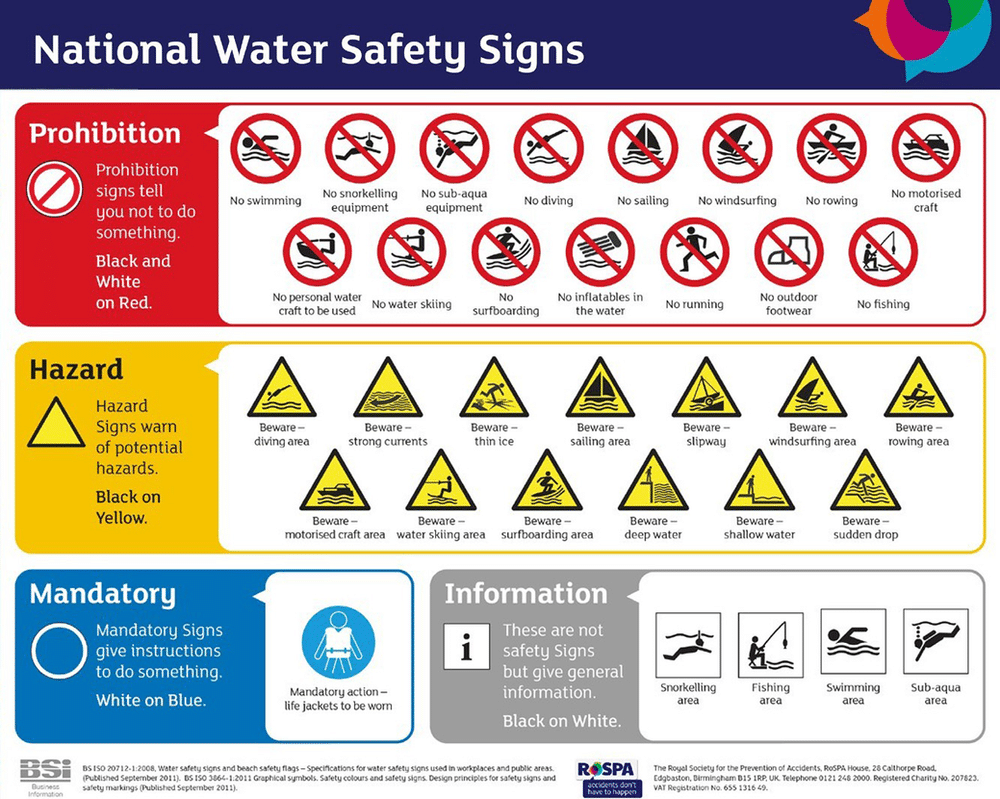

Signage

Written material on safety signs should meet technical writing standards for precision, accuracy, and logical organization. Graphical elements should exhibit these characteristics as well.

Various standards-publishing bodies provide standardized good practice guidance on safety sign content (and other safety standards), as below. These standards-publishing bodies include the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the national-level equivalents, such as the Royal Netherlands Standardization Institute, the American National Standards Institute, and the Japanese Industrial Standards Committee.

Following a 2021 multiple drowning during a paddleboarding trip in the UK, the Marine Accident Investigation Branch cited as a possible contributing factor that safety signs by the river did not follow safety sign standards, and that the signs used jargony language (“portage”) that might not be commonly understood by stand up paddleboarders.

Use When Appropriate

Not all writing should use technical communication convention, however.

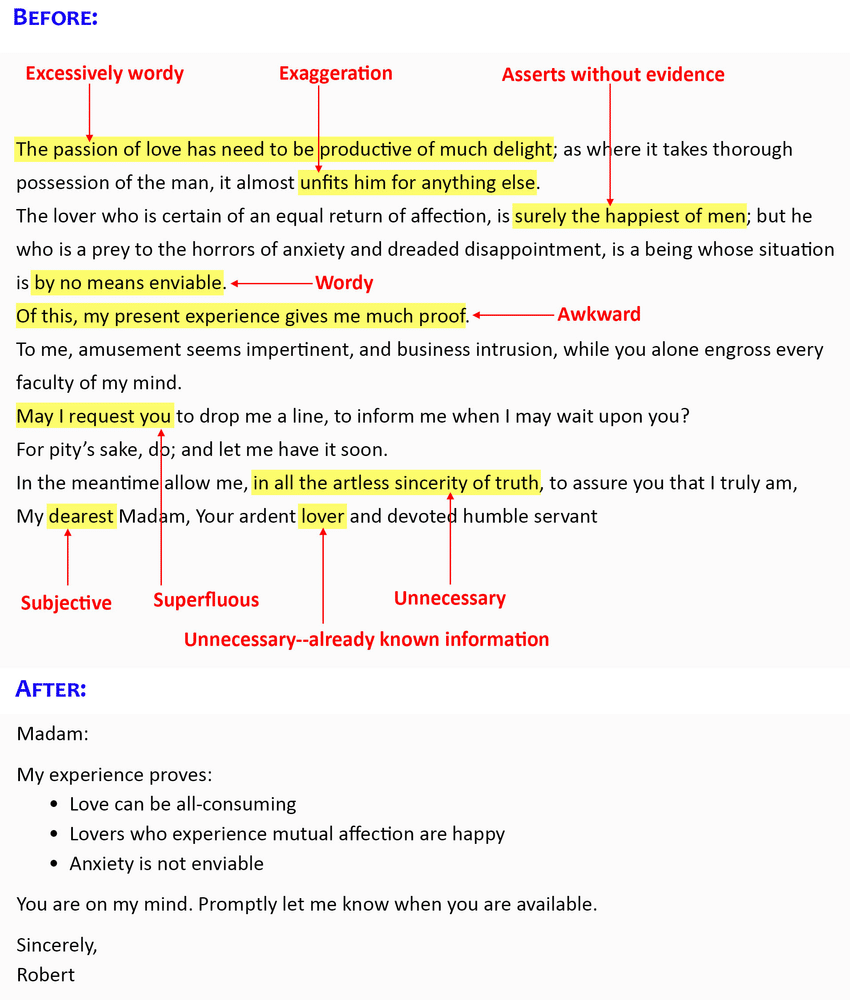

Consider this famous love letter from Robbie Burns, the national poet of Scotland, in its original text, edited and re-written in technical writing style:

For Further Information

Technical writing is a part of the field of technical communication, which grew out of the need to effectively and efficiently share information—in writing, visual and other media—about increasingly complex commercial and industrial processes and products in medical, military and other fields.

The field of technical communication has its own membership association, the Society of Technical Communication, with a conference, academic journal, and other resources.

Have an unconstrained passion for technical communication? Four-year university degrees in Technical Communication are available.

Conclusion

The smallest changes in punctuation matter, as evident in the difference between “Let’s eat, grandpa” and “Let’s eat grandpa.”

In Maine, the case of the USD 5 million comma led the state legislature to re-write the law to include punctuation between “packing for shipment” and “or distribution.”

The Maine case is just one in a series of legal situations where a single comma—or its absence—made a big difference.

The matter of a single comma has had an impact, in various court cases, on CAD 1 million in telecommunications expenses, USD 2 million in tariff charges, and the death of a defendant in a treason case.

These examples remind us of the importance of good technical writing—precise, accurate, and clearly and logically organized—in creating safety documents for outdoor, travel and adventure programs.