Whence Incidents?

Why do accidents happen? And how do we stop incidents from occurring—and is that even possible? These are questions that individuals with the responsibility for managing risks across many industries—from the outdoors to petrochemical extraction, aviation to healthcare—ask, as risk managers seek to reduce the probability and severity of loss from incidents.

In the professions of outdoor recreation, outdoor education, experiential adventure and related disciplines, individuals without extensive exposure to risk management theory informed by research in human factors and other scientific areas of inquiry may, when considering outdoor safety, focus on topics such as the contents of the first aid kit, appropriate use of technical outdoor gear, activity leader qualifications, and the presence and content of emergency response plans. We’ll explore that this approach to risk management is useful, but not enough.

Incident Causation Models Should Consider Direct Factors

Evaluating the polices, procedures, values and systems contained in the risk domains such as equipment, activities and program areas, participants and staff is an important element of good outdoor risk management. A variety of models have been put forward to identify some of these risk domains—areas where risks reside—that directly affect probability and severity of incident occurrence.

The Risk Domains model identifies eight: Organizational Culture, Activities and Program Areas, Staff, Equipment, Participants, Subcontractors, Transportation, Business Administration.

Other models that look at factors influencing incident causation, each of which may have multiple variants, include the well-regarded AcciMap model developed by Rasmussen, the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) employed by the US Navy, and STAMP (Systems-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes), among others. (A multitude of models exist; any model is not an exact replica of reality, and every model has its benefits and drawbacks.)

Underlying Factors Must Also Be Considered

One of the features, however, of well-developed accident causation and prevention models, such as those described above, is an analysis of not just the directly involved factors in the incident-factors such as faulty equipment or improper technique—but underlying factors that may influence the probability or severity of loss.

In the Risk Domains model, these underlying factors are: Government, Society, Outdoor Industry, and Business. Government refers to the presence, absence, quality and enforcement of compulsory regulatory regimes designed to manage risk. Society refers to factors such as social risk tolerance—for instance, the degree of public outcry following a significant safety incident. Outdoor Industry refers to effective self-regulation, for example by the presence of high-quality qualifications schemes, internal (non-governmental) accreditation, standards-setting bodies and consensus standards conformity, and intra-industry information-sharing systems such as research periodicals and conferences. Business refers to the influence that large corporations in particular wield through lobbying, political activity and other means, to support or degrade the government’s capacity to institute effective risk management regulatory regimes, for example through an occupational health and safety agency.

So, ensuring the first aid kit is well-stocked, equipment is well-maintained, and that activity leaders are well trained are good. But there’s more to comprehensive outdoor risk management.

Here we’ll look more closely at the factor of regulation by government authorities.

The Role of Government Regulation

It’s easy to agree that a certain amount of government regulation is a good thing, to preserve a measure of social order and equity. Economists, political scientists and others can point to the demise of governmental functions in settings ranging from the Bronze Age Collapse to modern-day Yemen as extreme examples of the deleterious effect of insufficient organized social leadership structures.

But agreement doesn’t go far from there. An ongoing conversation continues regarding just how much regulation is enough, and the content and subjects of those regulations.

A comprehensive discussion of the topic of regulation overall is not the objective here. But it can be useful for outdoor professionals to consider current thinking and research into how regulation may influence safety outcomes in wilderness, adventure, experiential and travel program contexts.

Some of the world’s best current thinking on outdoor safety comes from Australia, including from thought leaders associated with the Centre for Human Factors and Sociotechnical Systems of the University of the Sunshine Coast, where sport and outdoor recreation comprises one of the Centre’s five core research themes.

The Perils of Self-Regulation

Dr. Tony Carden, whose 2019 doctoral dissertation at the Centre looked at regulatory system design and evaluation from a systems approach, has worked in the led outdoor activity sector for over 20 years, and brings a confluence of expertise in regulatory system evaluation and outdoor programming. Dr. Carden’s research points to the effectiveness of regulation and safety standards in accident and injury prevention in general, for instance in federal motor vehicle safety standards in the US (https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812069).

Carden also identifies key principles of good practice in regulatory system design, based on research in sociotechnical systems and regulation. These system-based design principles include the idea that regulations should primarily influence management (referencing research indicating “the most important factor in the occurrence of accidents is management commitment to safety and the basic safety culture in the organization or industry,” (Dr. Nancy Leveson, https://www.skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/409.pdf), and that regulations should be generic and avoid overspecification (such as in ‘principles-based regulation’ described by Prof. Julia Black, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35436052.pdf).

However, we’ll focus here on another of Carden’s key good practice principles: avoid reliance on self-regulation. This may be anathema to some outdoor adventurers who prize independence and freedom from onerous regulations. After all, bureaucrats in a far-off capital city don’t know much about running rapids, scaling cliffs, or trekking through wilderness landscapes, they may argue. But what does the research on this topic have to say?

Carden brings to our attention evidence that “‘pure’ self-regulation is rarely effective in achieving social objectives because of the gap between private industry interests and the public interest” (Neil Gunningham, http://regnet.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2015-04/NG_investigation-industry-self-regulation-whss-nz_0.pdf).

Dr. Gunningham suggests the optimal solution may be a blend of self-regulation, government regulation, and third-party oversight (such as through, in our case, an outdoor industry standards-setting body). Gunningham describes the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear reactor partial meltdown incident and the industry response, to create a third-party body, the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, to establish industry safety standards. However, lacking the enforcement power of law, the INPO found itself incapable of fully achieving its safety aims, and turned to the government regulator, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, for support.

Similarly, Dr. Florian Saurwein notes evidence indicating that pure self-regulation is unsuitable with regards to content-rating in the audiovisual industry, supporting “some kind of governmental control.” (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232258536_Regulatory_Choice_for_Alternative_Modes_of_Regulation_How_Context_Matters) Saurwein gives as an example the motion picture industry in the USA, where the Motion Picture Association (formerly the Motion Picture Association of America, MPAA) provides industry self-regulation of audiovisual media content, but only under the regulatory eye of the Federal Trade Commission.

Finally, Dr. Charles Woolfson (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235404704) describes the “preventable and foreseeable” 2011 Deepwater Horizon offshore oil disaster, following the similar Piper Alpha explosion and fire in 1988, implicating self-regulation (and regulatory capture) as a contributing factor.

(In asking why the Deepwater Horizon incident occurred, Woolfson responds, “The answer tells us much about the ability of corporate capital to configure regulatory regimes in its own interests and to do so in a manner that continues to threaten the safety and well-being of its employees and the wider environment.”)

That said, generalities such as this are just that: generalities, and there may be circumstances where, for instance, self-regulation is effective, such as with large and high-functioning corporations with high reputation sensitivity which have the capacities and motivations to self-regulate. (The outdoor industry, however, is not rich in such types of provider institutions.)

Self-Regulation and the Outdoor Industry

In the early 1990’s, outdoor activity centres in the UK were not subject to detailed regulatory requirements from the national government. This all changed, however, on March 22, 1993.

The Incident

It was a beautiful morning to be out on the water. At around 10 am that day, eight students and their teacher launched from the sandy harbor, accompanied by two professional outdoor guides, for a two-hour kayak trip. They would paddle a few kilometers down the shore of Lyme Bay, on the south coast of England, then return. They’d be back by lunch.

Not long after launching, one of the participants capsized. As one instructor worked with him, the second instructor rafted the other kayakers together in a group. Winds pushed the flotilla of kayaks so far from the first participant they could no longer see each other.

The wind-blown waves were now one meter high. One of the kayaks was swamped, then another. Eventually, all nine kayakers were in the eight degree Centigrade water. They were swept out to sea and became separated from each other, spreading over an eight-kilometer area.

Noon came and went. Although the group was supposed to have returned by now, nobody at the outdoor program initiated a search and rescue process or alerted the authorities.

An upturned boat was discovered by a fisherman, who called the coast guard. A lifeboat and helicopter went to rescue the boaters. The rescue began close to four hours after the group was supposed to have returned to shore.

Four of the students drowned.

Analysis

An investigation reported that the kayak instructors were not highly experienced, with one only having paddled a total of 400 meters previously. The instructors were not carrying flares or a VHF radio. The victims blew their emergency whistles but this was not effective.

Conclusions

The tragedy was found to be preventable. The outdoor program failed to properly organize the kayaking program. It failed to employ appropriately trained guides. And it failed to put in place and properly use emergency procedures.

Recommendations and Action

The owner of the outdoor program was convicted of “gross negligence manslaughter,” and was jailed for over a year. Also as a result, a governmental regulatory body, the Adventure Activities Licensing Authority, was created in the UK to control commercial adventure activities. Government regulations then replaced voluntary codes that could be used by outdoor activity organizations.

(The adventure activities regulations are now generally well-accepted by industry, some grumbling about matters of expense and management burden notwithstanding, but has always had critics who push to weaken or dismantle the regulations.)

A Repeat, in New Zealand

A similar tragic incident occurred 15 years later, in New Zealand. At a well-respected outdoor center, seven participants on an outdoor adventure program drowned in a flood during a canyon hike. (https://www.viristar.com/post/risk-management-case-study-mangatepopo-drowning-new-zealand-2008)

At as with the Lyme Bay tragedy, the Mangatepopo Gorge incident resulted in national safety legislation targeted to outdoor adventure activities.

What are the Implications?

In both cases, when preventable tragedies occurred—even in the presence of industry self-regulation—the government stepped in with detailed regulatory structures to reduce the probability that such tragedies would occur again.

However, in both countries—and in many others—third-party organizations that set standards continue to play an important role in managing risks of outdoor safety. In the UK, for example, British Canoeing is among a multitude of national governing bodies/peak bodies and qualifications-awarding entities. Members of the International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations set useful mountaineering standards. Accrediting organizations such as the Australian Camps Association and the Association for Experiential Education accredit camp programs and experiential adventure activities.

The influence of self-regulation and government regulation, among other factors, in managing risks of outdoor adventure programs, was illustrated in the tragic 2001 death of a young person at a home-made ropes course in Australia. The coroner found contributing causes to include the failure of government health and safety inspectors to identify problems, an ineffective accreditation system, a loophole in occupational health and safety law that exempted the ropes course element from regulation, and an absence of oversight of adventure programs by the government.

Other, non-regulatory, factors, included equipment misuse, failure to provide a backup system in case of component failure, and failure by the operator to mitigate the increased risk from the participant being positioned upside-down. (http://www.outdoorcouncil.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/VicCoronial.pdf)

We can see, then, how both governmental regulation and self-regulation are among the multiple factors than can influence safety outcomes in outdoor and adventure programs.

What’s the Optimal Outdoor Program Regulatory Regime?

Academics such as Carden, Leveson, Black, Gunningham, Saurwein, and Woolfson, mentioned above, explore some of the many complexities of regulatory systems. Specialists devote their careers to elucidating best practices for the role of government, and how they differ depending on multitudinous variables across economic, cultural, industry-specific and other contexts.

The responses reflect the complexity of the situation, where different values, experiences, and norms from outdoor professionals around the world lead to substantially differing opinions.

Just as the debate around the role of government in other aspects of life continues, there are no simple and universally applicable answers that provide a comprehensive outline of an optimal regulatory regime. Widespread agreement exists, however, that well-designed regulatory structures have an important role to play in supporting good risk management for outdoor and experiential programs.

Carden and his colleagues at the Centre for Human Factors and Sociotechnical Systems recognize that led outdoor activities represent a complex sociotechnical system. (https://psalmon2014.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/notassimpleties_preprint-1.pdf) One of the characteristics of complex sociotechnical systems is that problems that appear in a system are best addressed with solutions that exhibit the same level of complexity as the system which the solution is designed to address.

This suggests that self-regulation, third-party regulation, and government regulation all have an important role to play in risk management for organized outdoor activities, but that the nature of those governmental and non-governmental regulatory regimes will vary depending on the unique circumstances of each situation.

Managing Complexity in Risk Management Regulatory Regimes

We’ve seen that balancing self-regulation and government regulation is not a clear-cut issue. And what are best practices in government regulation schemes (as Dr. Black asks: regulation based on principles? rules? process? outcome?) is similarly a subject of ongoing conversation and debate. So, too, are subjects involving risk management regulation in specific.

Andrew Hopkins of the National Research Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Regulation notes, “The aim of risk management is to identify and reduce risks. But how far do managers need to go in reducing the level of risk? How low is low enough?” (http://regnet.anu.edu.au/research/publications/3016/wp-25-quantitative-risk-assessment-critique)

Health and safety regulators are tasked with obtaining answers to these questions. Responses like “as low as reasonably practicable” (ALARP) and “so far as is reasonably practicable” (SFAIRP) have been given by regulators, particularly in British Commonwealth states, but leave open questions of what then is ‘reasonable’ and how to measure whether something is ‘practicable.’

Quantitative risk assessment (QRA) has arisen in order to give systematic guidance in answering these questions, and is in wide use in the form of risk assessment spreadsheets. These graphs are typically intended to list all applicable risks, evaluate risks as to how likely they are to occur and how severe the consequences of the occurrence will be, and associate control measures with each enumerated risk, with measures being stricter as the likelihood and severity rise.

This linear risk assessment approach is required by some government safety authorities, such as the UK’s Health and Safety Executive under the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 (https://www.hse.gov.uk/simple-health-safety/risk/index.htm), which provides templates and examples for guidance (https://www.hse.gov.uk/simple-health-safety/risk/risk-assessment-template-and-examples.htm).

Hopkins continues: “QRA is built on the assumption that risk can be objectively measured.” This assumption, however, he notes, is “thoroughly problematic.” If we recall that even activities as apparently simple as an activity leader taking a group for a hike in fact are, as Carden points out, complex sociotechnical systems, we know that at least some risks in those systems are inherently unpredictable and can unexpectedly emerge from the interaction of different system elements.

But suppose a significant risk has been identified. What’s an acceptable fatality rate? Is this a moral decision? A financial decision? Correlated to the natural rate of death in day-to-day activities in the region? Is the life of a young person worth more than an older person? How much money is “reasonable” to spend in preventing the loss of a life? Regulators must grapple with these questions.

Hopkins also raises the question about spending money to prevent fatalities in one area as opposed to another. For example, installing Automatic Train Protection (ATP), which automatically applies the brakes to a speeding train, would save lives at the cost of 30 million British pounds per life saved. But taking steps to reduce road fatalities would cost only 0.1 million pounds per life saved. Should the portion of rail ticket fees collected from train passengers that could be used to install ATP instead be used to effect road improvements?

Finally, Hopkins reminds us that significant risks cannot be captured by simple risk assessments. He concludes, “The most significant risk is poor management and this is inherently unquantifiable. QRA is largely inappropriate, therefore, as a means of deciding whether risk has been driven to a sufficiently low level.”

Limits to Outdoor Safety Regulatory Regimes

Following the Mangatepopo Gorge tragedy, New Zealand instituted perhaps the world’s most comprehensive and effective legislation specifically addressing safety in outdoor and adventure activities, the Health and Safety at Work (Adventure Activities) Regulations 2016 (https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2016/0019/latest/DLM6725703.html). Combined with the outdoor industry’s internal resources (https://www.supportadventure.co.nz/), this resulted in a public-private outdoor safety structure seen as a global role model.

However, even what is considered a world leader in outdoor safety regulation was challenged by the December 2019 volcanic eruption at Whakaari/White Island, in which 22 people died, despite island visits having required an independent safety audit under the adventure activity regulations. (https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/about-us/news-and-media/13-parties-charged-by-worksafe-new-zealand-over-whakaariwhite-island-tragedy)

Seismic tremors and sulfur dioxide emissions had indicated an increased likelihood of eruption, so the eruption was considered foreseeable. Organizations involved in the island tours were charged in November 2020 with failing to ensure the health and safety of workers and others.

This tragedy may offer a bitter lesson on whether there are opportunities to improve New Zealand’s regulatory regime for managing risks of adventure activities.

Northwest of New Zealand, across the Tasman and Java seas, Singapore has a strong tradition of outdoor adventure, including for school children as part of the Ministry of Education’s National Outdoor Adventure Education Master Plan. And the Ministry has a reputation for taking risk management seriously, and being a leader in Asia and beyond in putting cutting-edge outdoor risk management theory into practice. The tragic death of a 15-year old student at the adventure sports centre in Singapore’s SAFRA Yushun facility on February 3, 2021, at a program run by an accredited private provider, again illustrates the challenge of even established leaders in outdoor safety in preventing serious incidents.

Investigations of the tragedy at SAFRA Yushun are underway, and providing they evaluate factors in both direct and underlying risk domains, may support regulators and others in improving risk management structure to help prevent further tragedy.

Conclusion

Risks in outdoor activities come from a variety of “risk domains,” such as equipment, staff, and activities. One risk domain that outdoor and adventure activity providers may not think of being closely tied to safety outcomes is the regulatory environment. However, in the complex sociotechnical system of led outdoor activities and experiential programming, the role of government and its regulatory practices in supporting safety should not be overlooked.

Regulation is widely seen as valuable for establishing baseline requirements and helping ensure somewhat of a level playing field for providers. However, regulation can also be seen as being unduly burdensome and poorly crafted. Applying the right design principles and incorporating the best and most current thinking in how incidents occur can help ensure regulations are the most effective and have the fewest negative effects.

Questions about appropriate regulation involve issues including the role of government, the value of individual freedom, and epistemological considerations in policy-making in the absence of complete information. We still don’t know enough about incident causation to stop incidents from occurring—despite our best efforts, planes will still fall from the sky, and hikers will still twist their ankles on the trail. However, evidence-based best practices around risk management and effective regulatory approaches are evolving and ever-improving, and outdoor program leaders and regulators can both recognize the benefits of well-crafted and well-executed regulation, and work towards making further improvements.

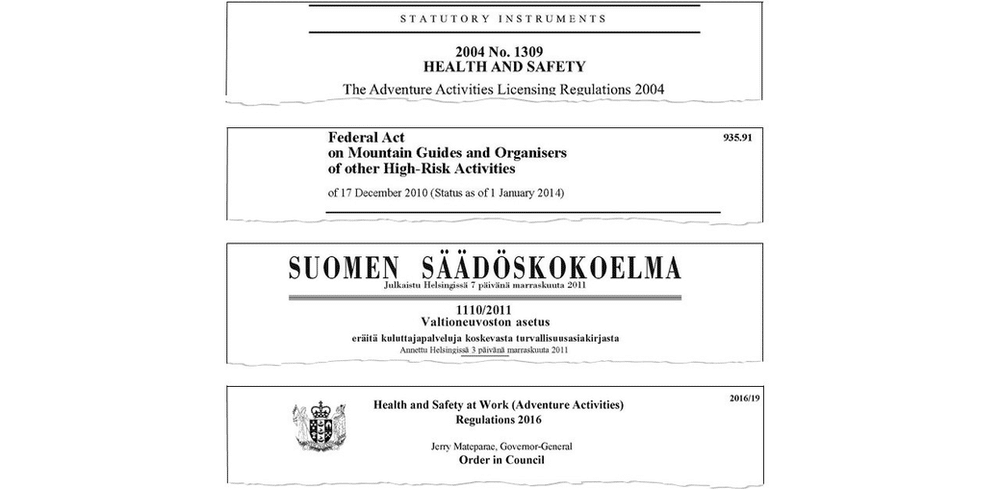

The image at the top of this article illustrates outdoor safety legislation in UK, Switzerland, Finland and New Zealand. Other jurisdictions have a variety of legislative and regulatory structures to support risk management for outdoor programs, and quality self-regulation through industry associations and others has an important role to play as well.

The practice and regulation of outdoor safety involves political science, systems theory, psychology, law, ergonomics science, and much more. Good risk management is breathtakingly complex, and good regulatory practice has similar complexity. We can look to well-respected examples of quality regulatory regimes influencing outdoor safety, such as those in the New Zealand and the UK, as role models, and we should not cease in efforts to improve all elements of the complex system in which we manage risk in outdoor programs.