The Right Support Can Help In Processing a Crisis Experienced in the Out-of-Doors—or Anywhere

Credit: Gery Lovász

Lorca Smetana was 16 years old in May of 1986, when she and a group of fellow students and staff from her high school began a climb of the snow-covered and glaciated Mount Hood in Oregon, USA. Lorca and others turned back for various reasons before reaching the peak. Thirteen members of the group continued on, but a storm arrived, bringing wind and snow. Trapped in the storm, seven students and two staff members died.

“How do you then go on to redefine a life that must have joy in it, to also include a history that includes tragedy, crippling grief, pain and long-lasting trauma?” This was the question that Lorca asked herself. It led her to a life of studying and teaching resilience, and the idea that through feeding her own resilience, she could hold both tragedy and joy together, in a generous and compassionate life.

Lorca is now a resilience coach and trainer, an expert in human resilience design who helps others come back stronger and richer inside, after living through crisis.

But this is not easy.

Maintaining mental health after directly or indirectly experiencing a tragedy in the out-of-doors can be a significant challenge.

Not everyone recognizes that survivors of a crisis, and those who responded to the emergency, can experience extreme psychological stress.

And individuals may be reluctant to disclose their guilt, fear, or other emotions. They may not know how to work through these feelings. And those around them may not be equipped to support them in processing their trauma and pain.

There is, however, a growing body of resources to support post-traumatic growth, and an increasing awareness of those resources.

Credit: Gery Lovász

It Takes A Village

Working through a traumatic incident isn’t something to be done alone. Healing happens best when a person has supportive friends, and often trained professionals as well, in one’s circle of healing.

The Workplace

But there’s more. When an incident happens in the context of a workplace—a ski patrol, a mountain guiding organization, an outdoor education program—the workplace has a responsibility to support the individual through their process of grief and recovery.

This means providing training to staff in advance of any incident on how to recognize and deal with psychological stress following a critical incident. It means fostering a community free of the toxic masculinity ideology that suppresses emotional expression and healing. It means having established policies around taking time off, access to counseling, bereavement leave, employee wellness, return-to-work flexibility, ways to reduce workload and stress for affected employees, institutional communications, and other organizational response to a critical incident. It means having insurance coverage, an Employee Assistance Plan, and staffing structures to support people taking time away from their job.

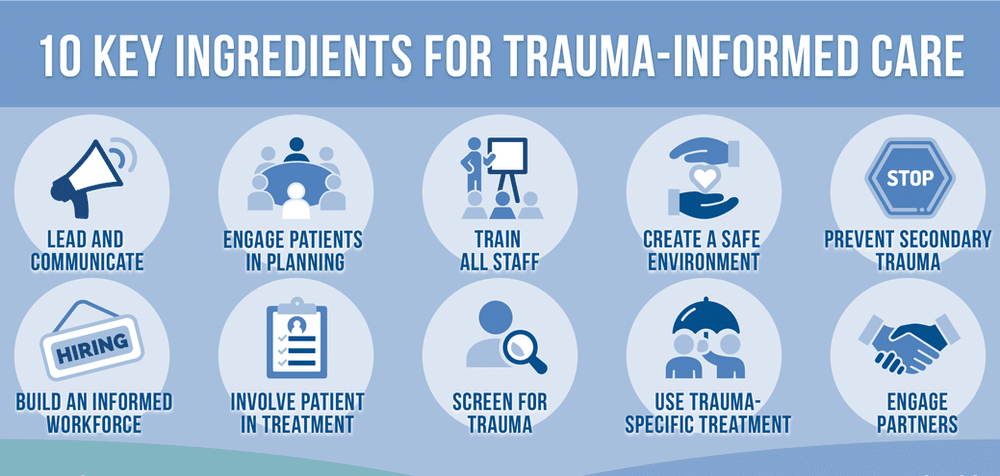

Organizations providing outdoor experiences can become a trauma-informed organization when they, among other things:

-

Ask “What happened to you?” instead of “What’s wrong with you?”

-

Provide opportunities for professional development

-

Promote recovery and resiliency

-

Promote self-care

-

Provide a safe environment

Industry Associations

Organizations outside the workplace have an important role to play as well. Industry associations (such as a mountain guiding association) are most effective when they proactively offer training, resources, and support for managing the after-effects of a critical incident—not just from the standpoint of technical incident analysis, but also for the psychological care of the survivors, responders, and others affected.

“A healthy mountain guiding community is a healthy community,” Lorca says. It’s predictable that critical incidents will happen in the mountains, she states—or anywhere outdoors. Industry associations are best when they recognize this, and proactively support resilience in the members of their community.

Credit: Gabriel Côté-Valiquette

Government Entities

Government organizations have a role too. Government agencies at the city, regional and national level can fund or operate crisis help lines, counseling centers, and other resources to support well-being and recovery.

Health Care Providers

Psychotherapeutic and medical care providers can also contribute to recovery. A growing emphasis on trauma-informed care helps improve outcomes. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, offer six principles that guide a trauma-informed approach to care:

-

Safety

-

Trustworthiness & transparency

-

Peer support

-

Collaboration & mutuality

-

Empowerment & choice

-

Cultural, historical & gender issues

The nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies offers additional guidance on trauma-informed care:

Credit: Center for Health Care Strategies

Individuals who have experienced a traumatic event sometimes feel alone in their grief, confusion, despair and guilt. But when the entire community—their family and friends, workplace, industry bodies, government agencies, healthcare providers and others—proactively and effectively rally around a person in a circle of caring and support, informed by best practices, then recovery is most likely.

Prepare for It Now

When a critical incident occurs in the out-of-doors, sometimes individuals affected, and organizations involved, scramble to figure out how to deal with the complex, stressful, and confusing aftermath. It’s better when preparations are made in advance of a critical incident—that will hopefully never occur, but which could come at any time.

Individuals

This means individuals building a network of social support in advance. Individuals can also pay attention to their levels of occupational stress and life stress, so that they have capacity to respond to difficult circumstances should they suddenly occur.

And it means having outdoor leaders and enthusiasts—and members of their community—understanding the warning signs of psychological stress injuries in advance, and having the knowledge and skills for how to begin to address them.

Credit: Gabriel Côté-Valiquette

Workplaces

And good preparation involves organizations whose staff or participants may experience psychological stress injury (a term some use to replace the phrase post-traumatic stress disorder) understanding best practices, and proactively creating a company culture and procedural guidance to support their customers, employees, and others if and when a critical incident occurs.

This can take many forms. It can involve the workplace managing the workload and stress levels of personnel. It can involve being operationally and culturally prepared in advance to reduce staff workload and sense of overwhelm immediately in the case of a critical incident. Encouraging—in more than words—staff to have a good work-life balance, get sufficient sleep, and support their own wellness—can also play an important part.

When a person is acting irritable, distant, or angry, managers in a well-prepared organization will not punish or isolate them, but instead recognize the person is in a place of need, and take skilled and compassionate action to support them. This can be seen as an example of Just Culture applied to trauma-informed care: not punishing a person for “acting toxic,” but seeking to understand and address the deeper factors that lead to challenging behaviors.

Resources

Let’s take a look at some of the resources available to individuals and organizations to support persons who have experienced a crisis.

Friends and Family

Strong social connections are one of the most important factors in recovering from a psychologically traumatic event. Having friends and loved ones who care about you, and who can listen attentively to you without judgment, can help you heal.

These can be family members, personal friends, colleagues, peer counselors or clinicians; they don’t have to be professionals.

Credit: Outdoor Taiwan

Skilled Persons

A therapist, psychologist, or counselor with the capacities to support individuals who have experienced psychological stress injuries can be very helpful—and, in some cases, life-saving.

But identifying a clinician or other trained provider who is able to offer this type of specialty care, and relate successfully to those who engage in outdoor adventures, is not always easy.

The Climbing Grief Fund, founded by Madaleine Sorkin after her experience of loss in the mountains, and housed in the American Alpine Club, offers a mental health directory of therapists. (Therapists are primarily North America-based but may offer virtual services globally.)

The New Zealand Mountain Guiding Association has published a list of experienced counsellors in New Zealand who can provide help with this kind of issue.

Julia Yanker is a trauma-informed transformational coach for adventurous athletes, specializing in working with outdoor adventurers who have experienced a traumatic incident in the out-of-doors.

Support Groups

Mountain Muskox provides a support network for people who have experienced loss or trauma in the mountains. Established after a fatal avalanche incident, the Canada-based group links peers and clinicians in a thoughtfully developed structure of group sessions, individual coaching and other activities over multi-month semesters.

Survivors of Outdoor Adventure Recovery, founded by Starr Jamison, provides a listing of counselors and therapists (primarily based in the USA) who have a specialty in supporting survivors of outdoor trauma.

Psychotherapist Benjamin White offers an online Mountain Process Group for those who have experienced a serious loss in the mountains.

The Climbing Grief Fund’s mental health directory includes a list of support groups.

Credit: Gery Lovász

Help Lines

Help lines are not a replacement for long-term counseling, in-person therapy, or the support of family and friends. However, in a crisis, they can provide valuable support.

The USA has a national mental health crisis line: 988. Launched in summer of 2022, it’s billed as “the 911 for mental health.” (911 is the national emergency number in the USA.) Dialing 988 connects people who are suicidal or experiencing any other mental health crisis to a trained mental health professional.

Previously, in the USA, people with a mental health crisis would call 911, but that emergency number wasn’t set up to address mental health needs. People would be directed to a hospital emergency department, facing delays, or would end up interacting with law enforcement, which sometimes led to tragedy.

Functionality and ongoing funding for 988 are yet to be firmly established.

Similar helplines exist in other countries around the world.

The Crisis Text Line, a USA-based non-profit, offers free 24/7 text-based support from a live, trained, volunteer crisis counselor, for callers from the USA, UK, Canada and Ireland.

The Trevor Project is a suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning) young people. Based in the USA, the Trevor Project provides support by phone, text and other formats.

Some employers offer an Employee Assistance Program to employees and sometimes their family members. EAPs often provide free, confidential helpline support and other mental health resources.

A variety of other helplines—for topics such as gambling, tobacco, and drug and alcohol addiction—exist. Local government agencies and other organizations provide directories of these crisis lines.

Organizations and Print Resources

The Responder Alliance connects responders and organizations with resources on resilience and recovery related to psychological stress injury, and includes a special focus on outdoor professionals.

Companies such as the First Responders Mental Health Alliance provide training and resources to support the mental health of first responders from law enforcement, military and other fields.

The American Alpine Club’s Climbing Grief Fund, mentioned above, provides mental health resources to those in the climbing, alpinism and ski mountaineering community. CGF offers financial support to those impacted by loss related to climbing. The Fund also offers educational material and a mental health directory of resources.

Survivors of Outdoor Adventure Recovery, also noted previously, provides educational resources and support for those involved in adventure accidents. The nonprofit also provides links to articles and other organizations offering psychological support to outdoorspersons.

The UK-based Zero Suicide Alliance provides training and resources the support people's mental health needs before, during and after a crisis.

The 2005 text Lessons Learned II by Deb Ajango discusses critical incidents in the outdoors and approaches for addressing them.

Psychological First Aid training

Psychological First Aid is care given to individuals following a serious crisis event. Lists of training providers and other resources are available from the American Psychological Association, the National Center for PTSD, and the World Health Organization, among others.

Credit: Taylor & Francis, IFRC

The awareness of the need for psychological first aid is increasing in outdoor programs, from Search and Rescue agencies to outdoor education/recreation providers. The training is increasingly being offered to outdoor leaders, for example by Mental Health First Aid Australia, the Appalachian Mountain Club in the USA and Mental Health Wilderness First Aid in Canada.

For clinicians, the text Outdoor Therapies discusses psychological first aid for outdoor programs in a chapter dedicated to that topic.

You Are Not Alone

Successfully dealing with a critical incident is hard—but it is possible.

“There is pain, and you have to live with it,” Lorca Smetana says, “and figure out how to move through it.” This is where resources are helpful—supportive friends and family, skilled counselors or therapists, support groups, and other help.

It’s possible to go from adversity to advantage after a crisis, and experience post-traumatic growth.

“There is a large amount of pain that is avoidable, that can be lessened,” Lorca says. When an individual grappling with a critical incident accesses peer and professional support, they can find ways to live with their challenging experiences and, she says, “still really live a beautiful rich life.”

Credit: Gabriel Côté-Valiquette