Fifteen-year-old Jethro Puah was an outstanding student at Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) in Singapore. His parents described him as “a caring and loving boy,” who was sensible and mature beyond his age.

On February 14, 2021, Jethro fell off a high ropes course element. The leg straps on his harness became unbuckled, and his loose harness slid up his body. Suspended in mid-air, his neck became compressed, and he died of traumatic asphyxia.

This tragedy followed an incident a year before, where a nine-year old girl fell four stories off a zipline in Singapore, fracturing her pelvis, elbow and hip.

Following these incidents, the government of Singapore prohibited public school students from participating in high ropes course and other height-based experiences. After a two-year pause, the government permitted height-based activities to resume, but with significant restrictions.

The Singaporean government also announced the establishment of a National Outdoor Adventure Education Council, composed of private sector and government representatives.

The Council, a number of whose members are alumni of Viristar’s Risk Management for Outdoor Programs training, was charged with establishing safety standards for outdoor adventure learning activities across the country.

After two years of intensive work, draft standards were released for stakeholder review in June 2024.

In January 2025, the final version of the standards was published by Enterprise Singapore, the government agency serving as Singapore’s national standards and accreditation body. The standard is Singapore Standard 710:2024, Code of practice for outdoor adventure education (OAE) activities.

The standards cover abseiling (rappelling), climbing, challenge courses (low and high), watercraft paddling and rowing, improvised rafting, camping, experiential learning initiatives and games (ELIG), and walking, hiking and navigation-based activities.

A number of other standards were referenced in developing the Code of Practice, including:

- SS 570-1:2022 Personal protective equipment for protection against falls from height − Part 1: Single-point anchor devices

- SS 570-2:2022 Personal protective equipment for protection against falls from height − Part 2: Flexible horizontal lifeline systems

- SS 607:2015 Specification for design of active fall-protection systems

- SS 681:2022 Code of practice for sport safety

- SS 701:2023 Code of practice for inland and open water sporting activities

Various other standards, mostly equipment-related, were also referenced, including those for fall protection, harnesses (UIAA, EN 12277), climbing structures (EN 12572), ropes/challenge courses (EN 15567 & ANSI/ACCT), and PFDs (ISO 12402-5).

Enterprise Singapore says the standard is designed “to help OAE activity providers deliver safe and educational experiences.”

The standard, Enterprise Singapore stated, “establishes a framework and describes best practices which can be used for creating or revising OAE activity programmes, while highlighting the unique safety requirements for the most common outdoor adventure activity types used for educational purposes in Singapore.”

Draft Standards vs. Final Version

Changes from the draft version to the final edition were generally minor in nature. Typographical changes occurred, and some copy editing improvements (such as describing an activity leader competency as “providing emergency response” rather than “emergency response”) were made.

The draft version described the document as covering “Management systems for outdoor adventure activities.” The final version notes the document is a Code of Practice. This can be an important distinction, as in some jurisdictions an Approved Code of Practice brings with it special legal protection.

Section 4.6.4.3 Hot Weather added requirements of activity leadership to institute rest breaks where necessary, and to suspend the activity entirely, if required for safety.

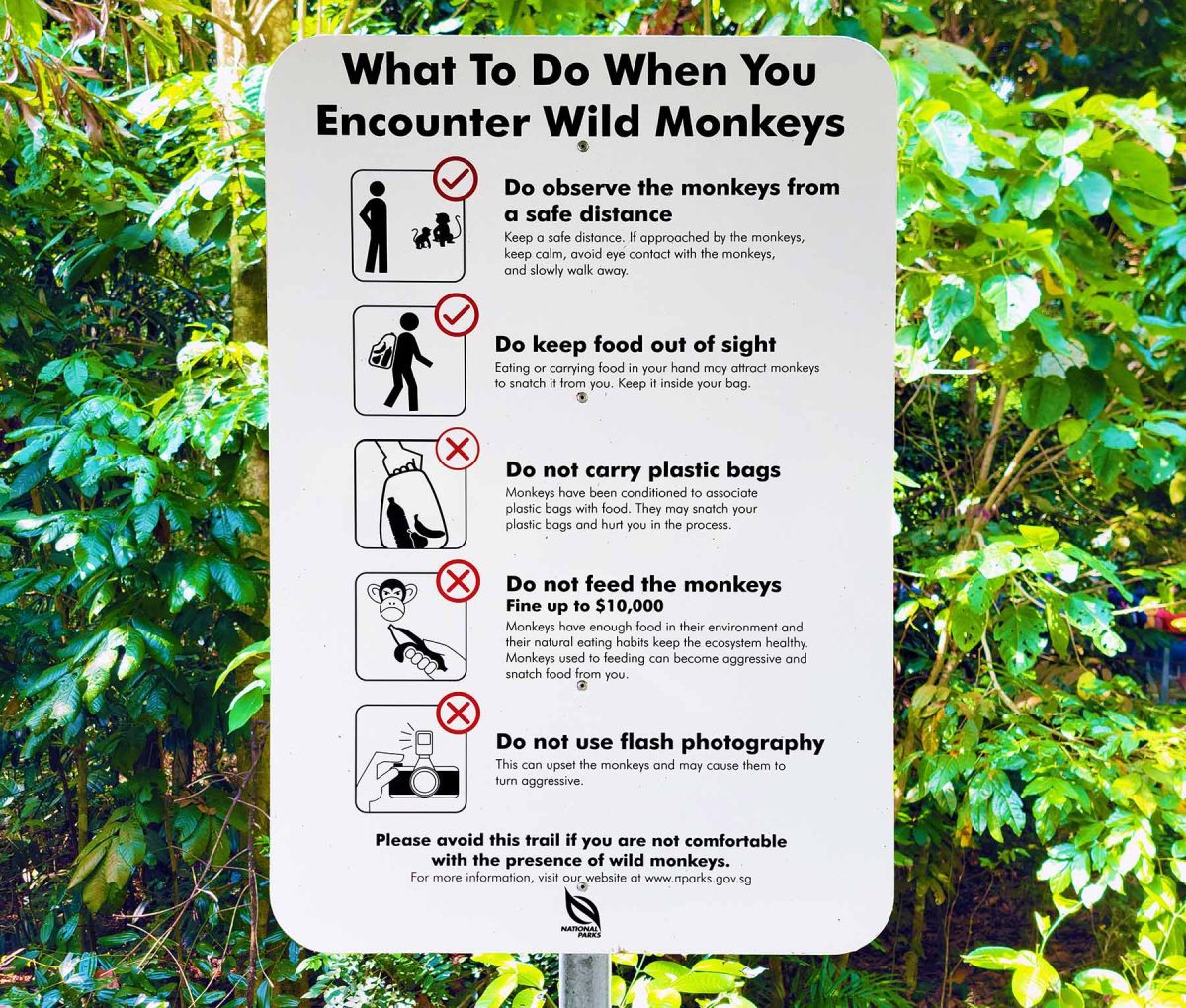

In section 4.6.9 Wildlife, a reference to the National Parks (Singapore) website for wildlife safety information was removed, but safety measures for Singapore-specific wildlife risks, such as those posed by troops of monkeys and families of otters, were retained.

A requirement for the activity provider to conduct abseil practice with participants prior to the commencement of the activity was added to section 5, Abseiling and climbing.

Section 7.7.4 on use of equipment in watercraft paddling and rowing activities newly noted that activity leadership shall ensure that PFDs are the correct buoyancy level for the person and the environment.

(The issue of proper PFD selection and use was highlighted in a recent drowning at a lake-side activity centre in the UK, where a government investigation found that the buoyancy aids during a boating activity used were “unsuitable and unsafe.”)

Recommended supervision types for paddling, rowing and SUP were combined.

Risks of camping were previously listed to include sleepwalking, harassment, theft and molestation; in the final version, the last item was re-worded as “outrage of modesty.”

Technical Writing Standards

Singapore’s Code of Practice, the creation of which was overseen by professional standards-development specialists from Enterprise Singapore, shows excellent use of technical writing convention, which is important for maximizing clarity and shared understanding of expectations.

The Code of Practice conforms to good practice for precision, accuracy, and clear, logical organization in technical writing.

For example, the document distinguishes between required, recommended and optional actions— “must,” “should” and “shall” items.

The document also avoids unfocused and rambling narratives, shows version and date control, is appropriately specific rather than vague, and separates items on individual lines, rather than mashing multiple items together in an extended narrative.

Singapore’s Outdoor Safety Standards vs. Other Outdoor Safety Standards

Singapore’s standards for good safety practice in outdoor adventure are thorough, carefully developed, and fine-tuned to the particular risks present in Singaporean outdoor adventure activities—from falling spiky durian fruit to the locally popular improvised raft-building.

The standards join a suite of other safety standards for outdoor activities around the world. These other standards—some voluntary, some compulsory—include, among others:

- The international mountain leader standards of the Union of International Mountain Leader Associations (IUMLA), newly revised in 2024

- The experiential adventure standards of the Association for Experiential Education

- The challenge course standards of the Association for Challenge Course Technology

- Adventure tourism safety guidelines in India

- Adventure activity standards in New Zealand and Australia

- Switzerland adventure safety requirements

- Adventure safety standards on the Arabian Peninsula

- The adventure safety accreditation standards from Viristar

Each set of standards has a specific purpose and audience. Some, such as challenge course standards, tend to be heavy on technical engineering specifications. Some—particularly those in high-income countries where adventure activities are a significant part of the economy or national values—are especially detailed and rigorous.

Singapore’s outdoor adventure education standards, produced by a coalition of adventure activity specialists, government bodies, health and safety experts, outdoor industry associations, universities, and representatives of organizations such as the Singapore Institution of Safety Officers and the Human Factors & Ergonomics Society of Singapore, overseen by the standards-development experts of the Singapore Standards Council, rank among the more professionally-formed and highly-developed standards in the outdoor and adventure sectors globally.

Adventure Safety Standards–A Growing Trend

The publication in Singapore of comprehensive safety standards, in a formal process involving adventure providers and government authorities, follows a growing trend around the world to both establish risk management norms for adventure providers, and put in place mechanisms to see that those standards have widespread adoption by industry.

For example, a recent triple drowning on a whitewater rafting trip in Malaysia led to calls to improve safety standards—and require their enforcement—in Malaysia’s growing adventure tourism sector.

The adventure travel sector in Japan has been advocating for the government to establish adventure safety standards, and incentivize providers to meet them.

The central government in China seeks a massive development of the outdoor sports sector there, including the development of safety standards; the private sector in that country also recognizes this need.

Voluntary adventure safety standards have been under development in South Africa, following the untimely drowning of a child in the Crocodile River at an outdoor education camp.

But in recognition that voluntary standards often have relatively low levels of adoption, adventure safety regulations are increasingly being passed into law.

These requirements, often but not always in the form of adventure tourism safety regulations, have been put in place everywhere from the UK to Oman.

Response from Singapore’s Outdoor and Adventure Sector

The 2022 announcement that the government of Singapore was initiating the development of a national standard for outdoor and adventure education safety and quality was met with a mix of gratitude and trepidation by Singapore’s outdoor adventure private sector.

Private operators, in an effort to demonstrate conformance to a high standard of safety and quality, had already developed their own adventure safety standards, some years before.

There was concern that the new standards would not be well-developed, or would be excessively burdensome. Yet, there was broad recognition that improvements needed to be made.

To its credit, the Singaporean government embarked on a multi-year, highly deliberative, inclusive process of standards development, systematically including the voices of private sector adventure operators.

The Safety and Quality Standards Committee of the Singapore Standards Council set up a Technical Committee on Personal Safety and Health, which established a Working Group on Outdoor Adventure Education to prepare the standard.

Along with Edvan Loh, Director for Learning & Sector Development at Outward Bound Singapore, Delane Lim Zi Xuan was Co-Convenor of the Working Group.

Delane told Viristar that reactions to the publication of the Code of Practice have been varied.

“Some providers and practitioners welcome the CoP as a necessary step towards raising standards, improving safety, and building public confidence in OAE,” Delane said. “Others are understandably concerned about what it might take to align with the standards—especially smaller companies or those with more limited resources,” he added.

Viristar asked what the impact on OAE providers might be.

“The standards are robust, and meeting them will require investment—especially in terms of documentation, training, and operational adjustments. For some providers, particularly smaller or newer outfits, there may be real concerns about feasibility. I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that a few might consider exiting the sector if they feel unable to meet the requirements,” Delane replied.

He continued: “That said, I also believe the CoP creates an opportunity to strengthen internal processes and develop stronger value propositions. As a community, we can find ways to support one another through this transition.”

Next Steps for Outdoor Adventure Education in Singapore

In Australia, adventure activity providers found it difficult to obtain insurance, as underwriters were unsure that adventure activities were being conducted with good risk management. Consequently, the Australian adventure sector came together to develop a nationwide adventure activity standard.

Some in the Australian adventure sector wish to see the voluntary standard be used in an accreditation scheme, where providers who show evidence of meeting good practice standards are awarded a publicly visible mark of accreditation. This can help potential customers understand if a given company meets broadly accepted safety standards.

Does the same potential trajectory hold true in Singapore?

Singapore’s Outdoor Adventure Education Council stated that the objectives of establishing the Code of Practice standards included aims to “serve as a reference for…accreditation and conformity assessment of OAE providers,” and to “guide government and regulatory agencies in drafting regulations.”

One senior executive at Outward Bound Singapore, which was active in developing the Code of Practice, mentioned accreditation as the logical next step in the process of helping ensure a high level of safety and quality in Singapore’s OAE sector.

The progression—if it occurs—is not likely to begin for a few years at least, so that adventure providers have time to understand and implement the standards of the new Code of Practice.

The private sector will benefit from a multi-year timeframe—as well as financial support from the government, for example to industry associations for the development of enhanced training schemes and auditing capacity. In New Zealand, which moved quickly to bring adventure safety requirements into effect after the untimely death of an adventure tourism participant, the rapid adoption of requirements with limited government support was criticized by the private sector.

The Singaporean government, however, has shown itself to be high-functioning and able to engage in deliberative, inclusive and effective policy development, and is the world leader in commitment to outdoor adventure education at the national government level.

Should Singapore’s Outdoor Adventure Education Code of Practice standards be incorporated into an accreditation scheme—or even a regulatory requirement—it’s likely that this will be done in a careful manner and in a way that sustains Singapore’s global reputation for leadership and excellence in outdoor adventure.