40 Years of Himalayan Mountaineering, From the Perspective of Outdoor Safety Management

by Vladimir Mesarić

Editor’s Note: This guest article on Viristar’s blog was written by Vladimir “Dado” Mesarić, a globally accomplished mountaineer, certified IFMGA Mountain Guide, 40-year Croatian Mountain Rescue Team member & instructor, and founder (and President of the Safety Board) of Outward Bound Croatia. Dado compares his experience with Himalayan mountaineering and training sherpas on the one hand, to the content of the Risk Management for Outdoor Programs course he attended and the course’s accompanying textbook, on the other. The article has been translated from the Croatian and lightly edited for clarity.

In July 2021, I was a student in Viristar’s course Risk Management for Outdoor Programs, and then, as an active participant in numerous outdoor activities with 50 years of experience, I recognized an interesting example of the historical development of Risk Domains.

In the late 1970s, I became a member of an alpine expedition to Mt. Everest ’79. In the spring of 1979, Yugoslav alpinists (21 from Slovenia, 2 from Croatia and 2 from Bosnia and Herzegovina), with the help of 20 high-altitude Sherpa porters, successfully climbed a new route to the top of the world—West Ridge Direct. On the way back from the top, one member of the expedition, Sirdar Ang Phu, was killed.

As I have been involved in two “projects” concerning the historical aspect of Risk Domains, I convey my view of this historical development.

This was a championship climb to the top of the world—one where some sections are so technically demanding, that the uneducated Nepalese, mostly from the Sherpa ethnic group, and who acted as high-altitude porters, needed—but did not have—expert skills for technical climbing and moving in the high mountains.

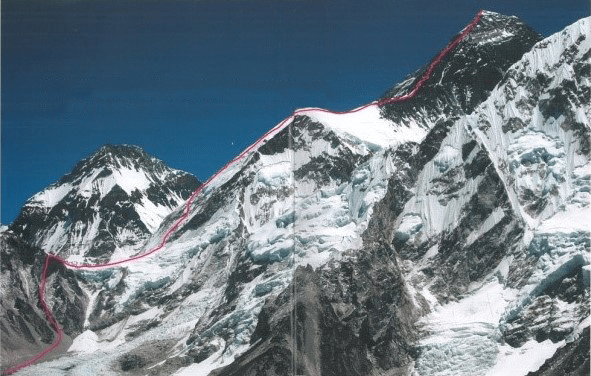

Mt. Everest—West ridge direct, first ascent, 1979. The summit successfully ended a two-month endeavor by the Yugoslav expedition. The Slovenian Route along the Western Ridge of Everest still ranks among the toughest Everest routes.

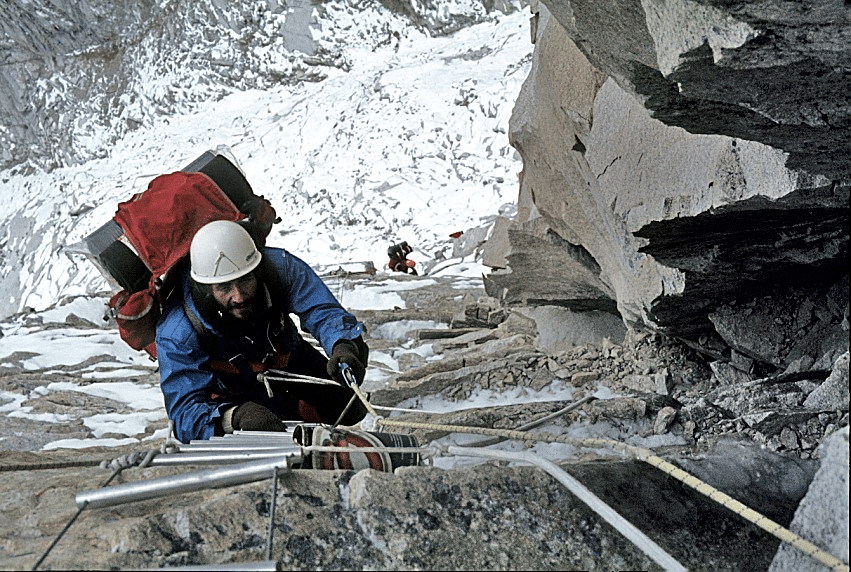

Everest West Ridge Direct—climbing section 5500 meters to 6000 meters

Sherpa people are strong and very well adapted to high altitudes, but, at the time, they were uneducated. They didn’t know how to climb, how to use mountaineering equipment, or how to communicate in foreign languages.

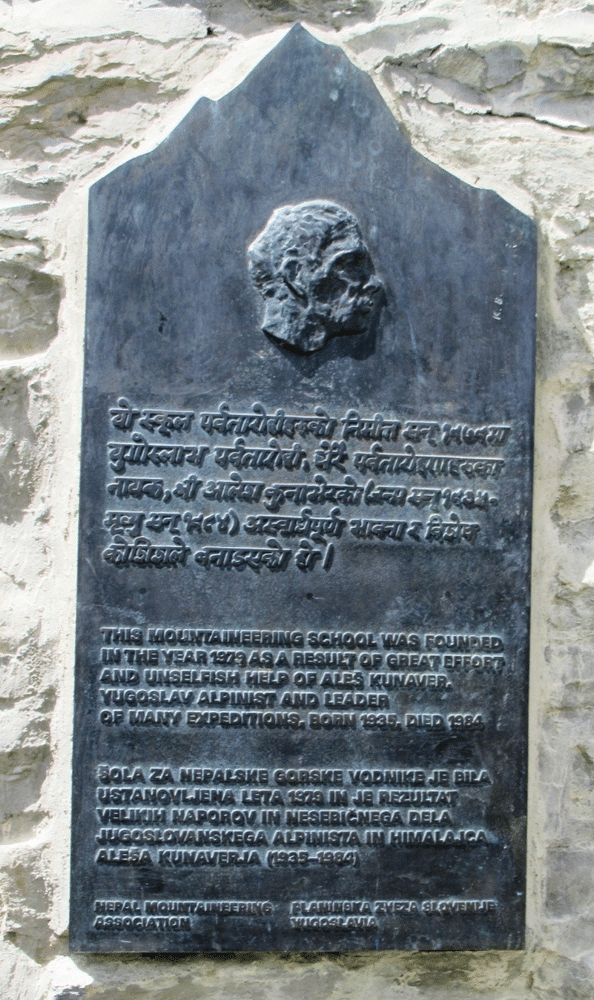

In the mid 1960’s, one man, Aleš Kunaver, a mountaineer from Slovenia (at the time, the country of Yugoslavia), got the idea to establish a mountaineering school for Sherpa, Tmang, Gurung and other peoples, in the heart of the Himalaya. The Manang Mountaineering School was opened in September 1979. The school was established in cooperation with the Nepal Mountaineering Association.

At the entrance to the Manang Mountaineering School, a plaque honoring Aleš Kunaver

In 1984 and 1990 I was an instructor at Manang Mountaineering School, and become a part of this historical development.

It has become quite clear that the development of mountaineering has moved in the direction that people living in the Himalayas and living from the Himalayas—mostly Sherpa, Gurung, Tamang peoples—will need knowledge to undertake the most demanding climbs and to solve the technical and logistical problems of “mass” tourism in the Himalayas.

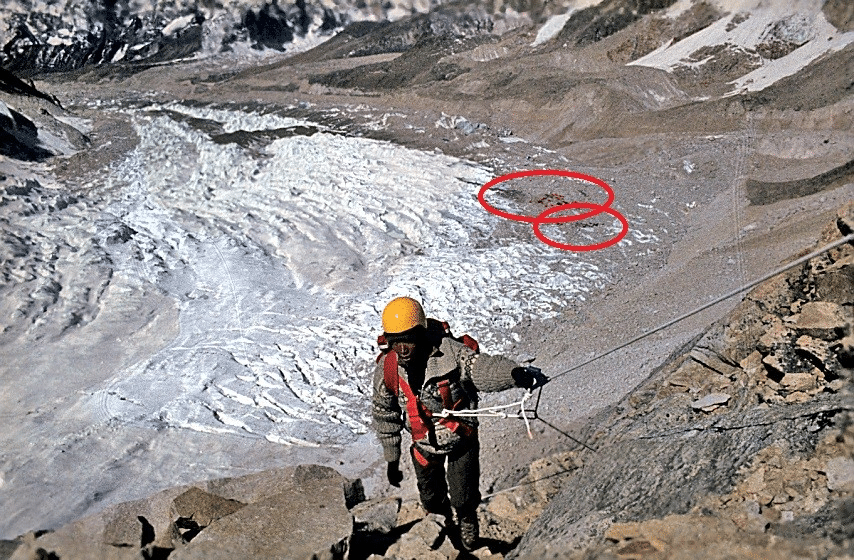

The view from Everest Base Camp towards Camp 1. The upper oval indicates the location of the Yugoslav Everest Base Camp, and the lower indicates the Austrian Lhotse Base Camp.

At the time, the Nepalese government issued permits to climb the highest peaks in the Himalayas for only one expedition team in one season: pre-monsoon or post-monsoon. In the spring of 1979, we were “alone” on the mountain.

In the picture above, it is clear that the Sherpas are porters who transport the equipment with the help of a fixed rope set by the climbers—members of the expedition.

Let’s look at this historical cross-section in the context of the Risk Management for Outdoor Programs model.

All activities related to mountaineering in the Himalayas (or anywhere in the high mountains) are very risky: I start with access to the mountain on bad roads, crossings over whitewater rivers, and walking trails exposed to landslides. The journey (trek) to Everest Base Camp, which for many who go there, begins with landing at the most dangerous airport in the world (Lukla), is extremely risky. Not to mention that a sudden arrival at an altitude above 5000 meters is an additional risk.

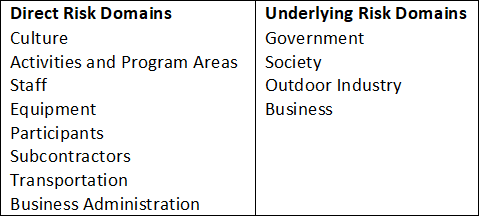

Here is an outdoor program risk management model with eight direct risk domains, plus four underlying risk domains:

The eight “direct” risk domains, along with the four “underlying” risk domains, can combine in various ways to lead to an incident. Risks in each “risk domain” are managed by specific policies, procedures, values and systems.

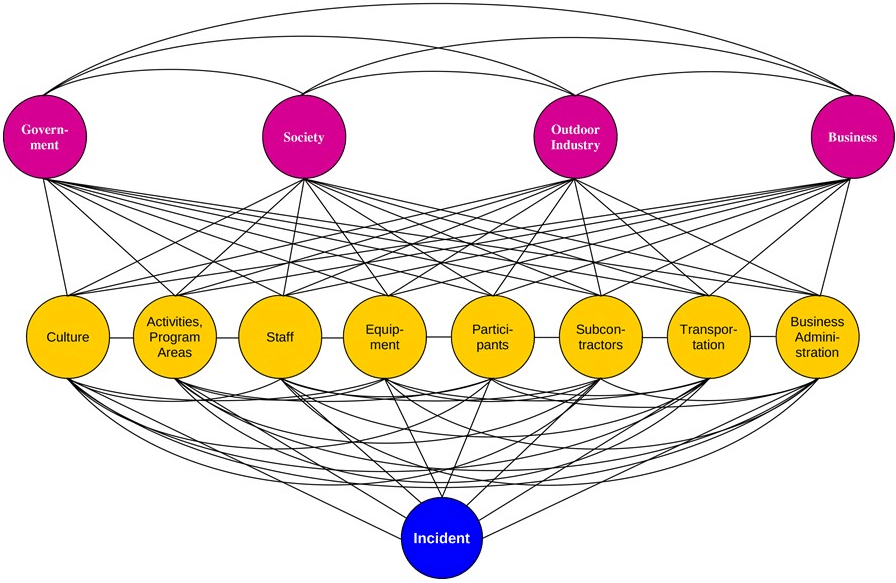

And broad “risk management instruments” help manage risk across multiple domains:

Together, the Risk Domains and Risk Management Instruments concepts comprise the Risk Domains model, illustrating how outdoor incidents happen and how they might be prevented.

Safety Culture in the Himalaya

At the beginning of this “chapter” I would add a quote from New York Times, September 10, 1979:

School Teaches Sherpas Mountaineering Skills

KATMANDU, Nepal, Sept. 10 (Reuters) —

The Sherpas of Nepal, who have long risked their lives accompanying more skilled foreign mountaineers on Himalayan peaks, now have a mountaineering school to teach them the latest climbing skills.

Though immensely strong and better able to function at high altitudes than other people, the Sherpas have been finding it increasingly difficult to match the advanced techniques of visitors. The new Nepal mountaineering training school, which began its first course this month, is also providing climbing training for the first time for three Sherpa women.

In Jeff Baierlein’s book we can extract subtitles such as: What is Safety Culture, and what are visible and invisible elements of Culture?

Mountaineers who come to Himalayas bring with them all their Safety Culture with their visible and invisible elements of culture. But Safety Culture among Himalayan people is different and under the great influence of Beliefs and Religion.

To establish all elements of safety culture in Nepal, the Manang Mountaineering School took time and financial resources. Initial financial input granted by the Yugoslav government enabled the construction of a school building in the Manang area (Humde village) and one-month courses for five years. After these five years, “Safety Culture” was still very far from being independently organized.

At the Manang Mountaineering School we worked to improve “Safety Culture in the Outdoor Context” and to “Establish Expected Behaviors.” We wrote all the first policies and procedures, prepared systems and structures, and started developing human resources components—we worked on elements of informal recognition systems such as awards and public recognition.

We tried and eventually managed to establish the Expected Way of Thinking. We were looking for ways to manage Continuous Improvement.

The Manang Mountaineering School

On May 15, 1979, three members of the Everest West Ridge Direct expedition—Stane Belak, Stipe Božić and Sirdar Ang Phu—stepped on top of the world and set off down the Hornbein Couloir. They were forced to bivouac at 8300 meters without bivouac equipment. They survived, and went down to meet the rescue team. The snow slope was hard but not glassy-icy, nor was it extremely steep.

At the moment the rescue team encountered the group returning from the top, Ang Phu slipped and fell 1500 meters on the Rongbuk Glacier.

Ang Phu had an ice ax in his hand, but did not use it at all, and did not try to stop at all, which would be a simple procedure for an experienced mountaineer.

Why didn’t he stop? Was he totally exhausted, or did the element of safety culture prevail, according to which mountain peaks are untouchable and the Gods are the only ones who only allow some people, and only sometimes, to reach the top?

We will never know, but in every Base Camp at the foot of the Himalayas the ascent begins only when the local people perform ritual worship—puja.

On September 10, 1979, the New York Times wrote:

The Sherpas’ lack of advanced mountaineering skills has meant they were less able to climb the technically difficult routes that foreign climbers turned to after the major peaks had been conquered by their easiest routes. It also meant that Sherpas had greater chances of serious accidents than they would have if they had had more knowledge of safe climbing techniques.

Only last May a Sherpa named Ang Phu, who had scaled Everest twice, slipped and fell during the descent with a Yugoslav team. Because he had not been trained in the technique of halting himself in such a fall, he plunged 2,000 yards down the north face of Everest and lies buried in a crevasse.

In all, 57 Sherpas have been killed in accidents or avalanches while climbing in the Nepalese Himalayas since Nepal first admitted foreign climbers in 1950.

In any case, we mountaineers from Slovenia and Croatia did great job in context of Safety Culture.

Activities And Program Areas

In Jeff’s book chapter “Activities-specific and Area-specific Topics,” I experienced almost all the mentioned risks.

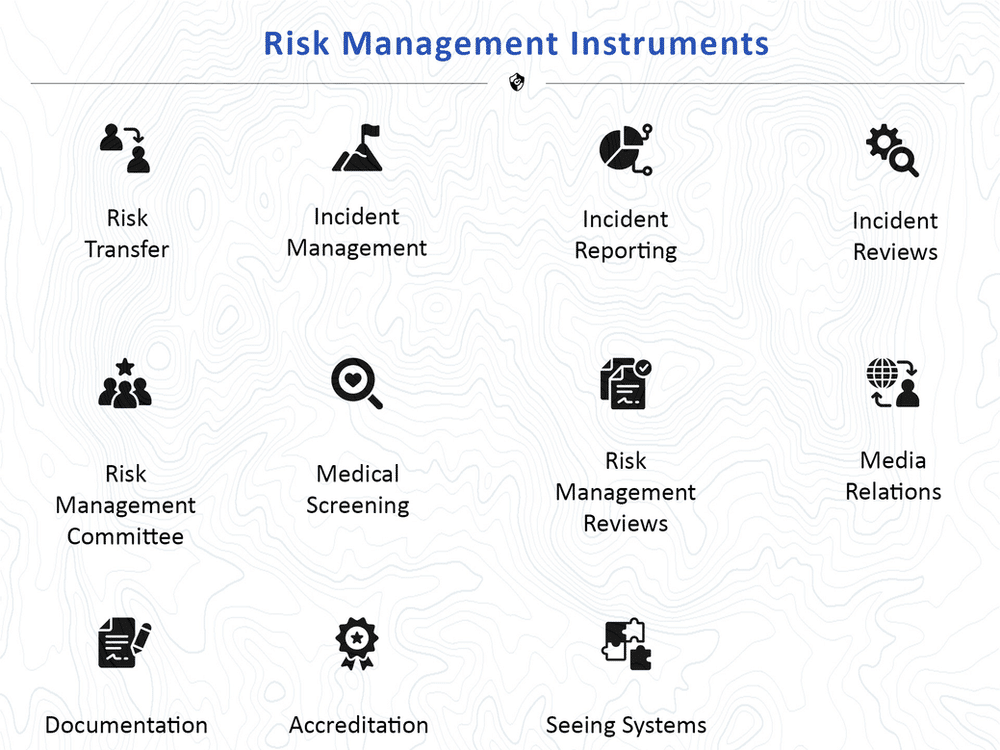

In my first trip to the school in Manang, the final tour was the climb the 6091-meter Pisang peak. The climb was successful, and all 25 participants were at the top with shouts of “Hurray”, hugging, shaking hands and waving the Nepalese flag, as was already the custom.

Of course, the climb is risky due to several elements of safety. Here I single out a few risks:

- Climbing in high altitude “above the clouds” is risky and some participants are more skilled and some are less skilled

- The ratio of the number of guides/instructors to the number of ascending participants was very unfavorable: 3/25

- Psychologically, arrival at the top of the mountain for some (inexperienced) participants is a moment of relaxation, with a drop in concentration and with “loss of nerve.” In euphoria, the participants quickly descended the steep mixed terrain: the frozen and dry parts of the terrain alternated and crampons had to be removed and re-installed frequently.

I was afraid of an accident which really happened: one student did not put the crampons on his feet and slipped, fell and suffered very serious spinal injuries. We had “live” elements of Risk Management Instruments: “Incident Reporting,” “Incident Reviews,” and “Documentation.”

Instructors organized a rescue operation, and the participants transported the victim from 5500 meters to 3300 meters, to the village of Pisang. After three days, he was transported by Himalayan Rescue Service helicopter to the hospital in Kathmandu, where he successfully recovered.

Manang Mountaineering School and Pisang Peak

What has changed in the last 40 years?

In the Risk Domain “Activities and Program Areas,” there have been many changes in the Annapurna area:

- One of the most beautiful trekking tours in Nepal—the Annapurna Circuit—actually disappeared, because the three-week trip is now shortened to less than a week, as the road from the east ends in Manang and in Muktinath from the west. Of course, both roads are risky, but the most risky element is crossing Thorong La pass with altitude of 5416 m; some trekkers are forced to go down to lower altitude because of mountain sickness.

- This improvement caused the opening of new opportunities for another activity: mountain cycling. Cycling around Annapurna over Thorung Pass would be the most challenging. But a much easier way would be cycling downhill from Manang where bicycles are transported up by bus or car.

- Another activity opened in this area is whitewater rafting on the Marsyangdi and Kali Gandaki rivers.

- In high altitude mountaineering access to all peaks has become more accessible, and ascents/expeditions are shorter (and cheaper).

- Another activity is the Annapurna Marathon, which is similar to the Everest Marathon.

Staff

Climbing instructors from Slovenia, Croatia and later from France were very experienced, and it was the best part of the story in the development of the Manang Mountaineering School. One Sherpa guide, educated in France at the well-known ENSA (National School of Mountain Sports) in Chamonix, was an instructor at the Manang Mountaineering School. Later on he established a travel agency in Kathmandu, organizing trekking and expeditions.

There was an intention and a plan to always have a doctor on the course, but sometimes it was not possible to find one. Doctors who came to the Manang Mountaineering School courses had the task of conducting a first aid class for the participants. On that occasion, they provided health services (treatment) to the population in the entire Manang Valley because there were no other doctors at all. On the other hand, these doctors had the opportunity to practice medicine “in times of disaster or war”—without trained support staff, equipment and medicines.

The staff in the organization that logistically organized the courses in the Manang Mountaineering School was only administrative. During the trip to Manang and during the course, the staff was only from the subcontractor. Over the years, course participants have improved their competencies and become instructors.

After the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, the Slovenian Mountaineering Association took over the full maintenance of the Manang Mountaineering School courses. The last course at the Manang Mountaineering School where there was an instructor from Slovenia (and only as an advisor) was held in 2013. So it took 34 years for Safety Culture to become fully established in Nepal.

Equipment

As instructors at the Manang Mountaineering School, we had our own personal equipment, but some young participants were poorly equipped. The school had enough gear, but it was sometimes poorly maintained.

Participants

When I was at the Manang Mountaineering School, we encountered a number of behavioral problems in the participants, but most were motivated to start working as soon as possible, on expeditions and treks.

Three groups of participants came to the Manang Mountaineering School:

- Most Nepalese work for travel agencies that offer trekking and expedition programs

- The second group are well-situated Nepalese who want to spend their time and money in outdoor activities through hiking—exactly what the Alpine Club of London established in 1857. Establishing the Manang Mountaineering School was one of the elements—a component of creating and developing outdoor activities in Nepal.

- The third group of students are non-Nepalese students from different countries: Americans, Koreans, Japanese and others. Students from regions with highly-developed Safety Culture wanted to be educated in real Himalayan environments.

Subcontractors

From the very beginning of expeditions in the Himalayas, subcontractors were closely involved.

Mountain Travel Nepal, founded in 1964, became the first commercial trekking company in Asia. All Slovenian Himalayan expeditions in the Himalayas were carried out with the help of Mountain Travel, including Everest ’79.

Organizing travel for the Manang Mountaineering School was too small a job for Mountain Travel, and on the other hand the Nepal Mountaineering Association wanted to develop its own, Nepalese trekking agencies.

Therefore, the Nepal Mountaineering Association nominated a subcontractor who organized all logistics tasks: local bus transfer, accommodation in Kathmandu and in lodges on the way to the School.

Transport of equipment and food was a special story: porters were used that carried more than 30 kg on their backs, yak and/or mule leaders. A chef with assistants was brought to the school.

Over the years, the Nepal Mountaineering Association has changed subcontractors in search of a more suitable partner.

Transportation

The journey from Kathmandu to the School in 1984 and 1990 lasted nine days. One of the most beautiful trekking trails, the Annapurna Circuit, started in Dumre on the Kathmandu – Pokhara highway. About halfway on that trekking route is the Manang Mountaineering School.

In the last 30 to 40 years, Nepal’s transport infrastructure has developed tremendously. Roads have been built to some of the most remote settlements, including Manang.

But despite that, driving on the Kathmandu – Pokhara highway is extremely risky, especially in summer during the monsoon rainy season. Landslides, demolition of bridges, and therefore several hours of traffic jams, are frequent.

In addition, control of many vehicles in Nepal is low, and breakdowns are common. Passengers must either wait for the breakdown to be rectified, or find replacement transport.

Two years after the Manang Mountaineering School was opened, Humde Airport was built, about two kilometers from the school. However, it operated very rarely. In recent years, the runway was paved with asphalt and was lengthened to 900 meters. It became a great opportunity for local people and for outdoor activities in the Annapurna area. But at that time we had no chance to use it, because of Safety Culture and Underlying Risk Domains and Business Administration risks in Nepal.

Business Administration

In the Manang Mountaineering School, we tried to establish a way of working as would a school “in the west.” We prepared all the necessary documents for the implementation of teaching in Yugoslavia, in Ljubljana, and during the implementation of the curriculum, the procedures were adjusted to the situations in the field.

The instructors tried to fix everything that could be done within Workplace Health and Safety.

The school building is built in the style of a traditional Manang house with a flat roof used for drying hay. This was not suitable for a way of use where the building was only in operation for a short part of the year and, due to the mud-coated roof, the roof started to leak. In 1990, therefore, the roof of the school building was covered with a sloping metal sheet. This saved the building from decay.

In terms of “human resources” and “staff”, in addition to instructors in Yugoslavia as well as Nepali instructors, a Nepali police officer was involved in teaching all topics related to legislation.

Risk Management Instruments

Over the years, instructors from Slovenia and Croatia began to develop the Risk Management System until the break-up of Yugoslavia. This process was continued by the Slovenian Mountaineering Association in cooperation with the Nepal Mountaineering Association. The development of a guide education system in the Himalayas has also continued.

As all instructors from Slovenia and Croatia were members of the Mountain Rescue Service, all Risk Management instruments related to incident management and reporting were established. Later, over the years, other risk management instruments were developed.

But more work needed to be done in this area.

Underlying Risk Domains

Government

Regulations related to the organization of expeditions and trekking were first drafted by the Mountain Travel Nepal agency, very close to the Nepalese government. The government has, above all, defined license prices for the highest Himalayan peaks.

Because of the tremendous increase in the number of mountaineers who want to scale Mt. Everest, the Nepal government announced new safety regulations on July 18, 2016. News media noted: “While the existing regulation only bars youngsters below 16 years of age from obtaining climbing permits, the draft prescribes a ban on climbers above 75 years of age from climbing the peaks.”

In 2002, the Nepal Government, under the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, founded the Nepal Mountain Academy to support mountaineering and adventure tourism.

Society

The Nepal Mountaineering Association was founded in 1973 with the goals of promoting mountaineering activities in the Himalaya, providing safety awareness and mountaineering skills to Nepalese mountaineers, and creating awareness of the beauty of the Himalayas both nationally and in international communities. The Nepal Mountaineering Association is an active member of the UIAA.

But in the beginning, the most important job of the Nepal Mountaineering Association was to issue and charge a fee for permits for “trekking peaks”—from 5500 meters to 6600 meters. Permits for peaks above 6600 meters are issued by the government.

The government later redirected the collection of fees for trekking peak permits to Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation.

But our story from 1979, opening Manang Mountaineering School goes on! A new mountaineering school was started in 2019, as the Nepal Mountaineering Association and South Korean Hum Hunggel Foundation entered an agreement to build a new mountaineering training school in Manang.

Also in the context of the underlying or indirect risk domain, Society, other very important organizations were founded, having to do with:

- Mountain Rescue Services

- Mountain Guides

- Mountain Leaders

Mountain Rescue

The Himalayan Rescue Association is a voluntary non-profit organization formed in 1973 with an objective to reduce casualties in the Nepal Himalayas, especially keeping in view the increasing number of Nepalese and foreigners who trek up into the remote wilderness.

In 2013 Alpine Rescue Service was founded. ARS provides emergency medical evacuation and assistance by land or air as well as associated support services.

Mountain Guides and Mountain Leaders

Twenty-six years after the first basic mountaineering course in Manang, outdoor risk management became developed to the point that a professional mountain guide organization was founded.

The Nepal National Mountain Guide Association, founded in 2005, is a member country representative of the International Federation of Mountain Guide Association (UIAGM/IFMGA). The NNMGA is accredited by the IFMGA to train and certify mountaineers in Nepal as qualified IFMGA Mountain Guides, a rigorous multi-year process.

The Nepal Mountain Leader Association, founded in 2015, provides first aid, mountain leadership, and mountain navigation training courses, each course five days in length. (Mountain leading refers to activities less technical than those conducted by Mountain Guides.)

Outdoor Industry

The modern-day outdoor industry in the Himalaya started with Colonel Jimmy Roberts who founded Mountain Travel Nepal, the first commercial trekking company in Asia.

Many Nepalis who completed courses at the Manang Mountaineering School started their own trekking agencies. Today there are more than a thousand of them in Kathmandu, Pokhara and all over the country.

A number of outdoor industry associations, and accrediting and certifying bodies, exist to support risk management in Nepal’s outdoor industry. Two examples follow:

The Trekking Agencies’ Association of Nepal, founded in 1971, organizes self-regulation of the trekking sector in Nepal to enhance the safety, quality and sustainability of trekking activities in Nepal.

Since 1989, the Nepal Association of Rafting Agencies provides river guide training, and works to advance river sports—rafting, canoeing and kayaking—in Nepal.

Business

Here I could add one specific example of this underlying risk domain: Mount Everest ascent.

In 1979, Yugoslav climbers were alone—there was only one expedition on the mountain. Today Everest climbing is really big business. In the spring and autumn seasons, Everest Base Camp becomes a tent town with hundreds of tents. Some are luxurious, with heated tents and plasma TVs. In the Khumbu area, on the way from Lukla to Everest Base Camp, there is wifi all the time.

Photos speak much better than words:

No longer is only one expedition on the mountain at a time.

Does corporate money supporting luxury at Everest Base Camp influence preparedness of clients?

Risk of exposure to severe weather is increased by traffic jams on Everest. Credit: Mingma Dorchi Sherpa

The big money involved in Everest guiding and permitting can incentivize risk-taking for profit.

At the end of this historical-modern story: in 2009, as the owner of a travel agency and as a mountain guide, I organized a trek around the 8,100-meter Manaslu, traversing the 5,200-meter Larkya La pass. I found a subcontractor in the form of a Sherpa agency from Kathmandu who was a student back in 1984 in a mountaineering course at a school in Manang.

On the wall in his agency was his diploma for completing a climbing course—which I, as the course leader, had signed.

I was proud to have been part of this historical story.