Saxet Brook flows through the idyllic mountain village of Saxeten, surrounded by the snowy peaks of the Swiss Alps. The region is famous for outdoor adventure activities—alpine hiking, paragliding, rock climbing, bungee jumping and canyoning in the summer, and ice climbing and skiing in the winter.

Just above the village, Saxet Brook (Saxetenbach, in Swiss German) flows through a steep-walled canyon, Saxetenbach Gorge. With exciting rock slides, jumps, waterfalls, and an abseil into a pool, the gorge is an attractive destination for thrill-seeking tourists wanting a guided adventure.

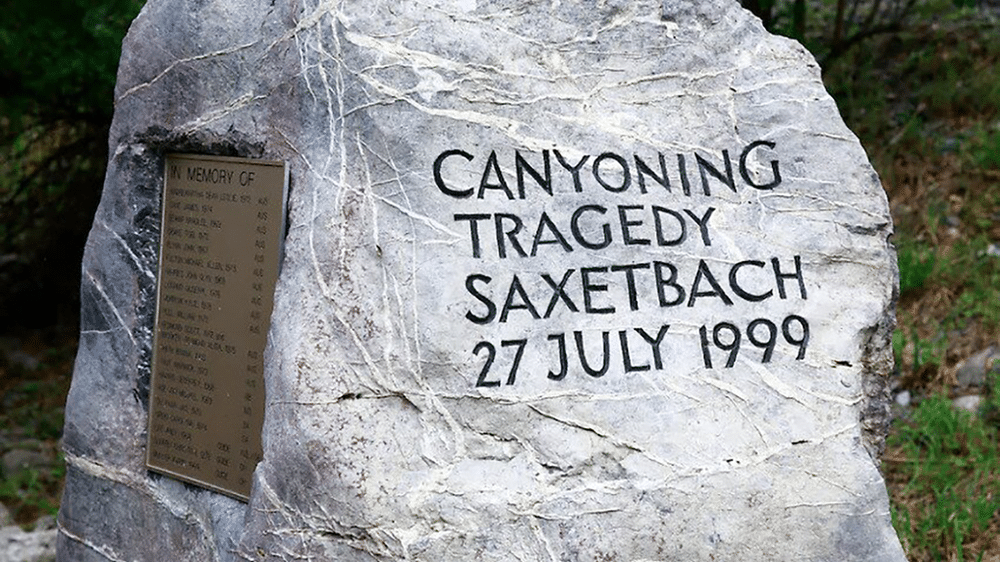

On July 27, 1999, a set of 45 tourists, divided into four groups and accompanied by eight guides, entered Saxetenbach Gorge for a two-hour canyoning excursion. The weather report called for thunderstorms, and it was raining as the group drove up to the canyon. There was thunder and lightning before the group entered the gorge, and the rain continued as the group started traveling down-canyon. As the group started down the gorge, the crystal-clear water had risen significantly, and had changed to a very dark brown.

Trip participants were spread along the canyon. Suddenly, someone screamed.

Participants looked up-river and saw a wall of dark water, two meters high, thick with logs and churning debris, descending on them.

Trip members had about two seconds to react. Some managed to scramble up the banks as the wall of water churned past them like an avalanche, watching helplessly as people who were upstream tumbled past them in the torrent. But two of the four groups were caught in the steepest section of the gorge, where the sheer cliffs make escape to the side impossible.

Eighteen trip participants and three guides drowned.

Company Denies Responsibility

The management of Adventure World, the company that organized the trip, acknowledged being responsible for safety. But, Adventure World staff said, there was nothing that could have been done to prevent the deaths.

“I don’t believe I made a mistake,” a manager said.

A lead guide called the incident an “unpredictable situation.”

A company co-founder said “it was a freak accident; completely unpredictable.” He claimed, “Adventure World is the safest, most professional water adventure company in the world.”

Criticism of Company Mounts

However, these assertions were soon called into question.

Experts and industry insiders criticized the company’s risk management practices.

In 1992, two professional guides from New Zealand were hired to establish Adventure World’s canyoning program. High safety standards were established. Guides had at least six years of experience.

The canyoning program immediately became popular.

But when the New Zealand guides returned in 1995, they saw that the pressure to serve more and more customers led to less-experienced guides leading canyoning trips.

“Things were getting out of hand,” one of the two New Zealand guides said. “The owners were getting greedy…I could see something bad was going to happen, and I didn’t want to be part of it.” He quit before the 1995 season was over.

The other guide noted, “management saw they could hire new guides for less.” Inexperienced guides, he said, were also more likely to do what they were told, even if it was unsafe. “There was so much overbooking that there was pressure to go when the weather wasn’t right, and the company knew the new guides weren’t going to stand up and say, ‘No, I won’t go.’” He, too, quit.

On the day of the incident, seven of the eight guides in the canyon were first-year guides.

An Issue of Safety Culture

The company’s safety culture was seen as feeding these poor risk management decisions.

The provider was criticized for putting pressure on guides to run expeditions, no matter the weather, since they were paid by the number of trips conducted.

One company employee said it was more than “financial concerns overtaking the safety standards,” however. He stated, “There was a macho attitude in the company.” The employee said that this attitude “is very dangerous when you’re taking people’s lives into your own hands every day.”

A storm warning system had been set up following a devastating Saxetenbach flood in 1987. On the day of the incident, the local fire department was on high alert, and the commander of the local fire and rescue services sent an officer to warn guides not to head into the canyon.

The firefighter stopped people who were entering the canyon. He warned the guides of a severe thunderstorm higher in the valley, making conditions dangerous. He told them they should not enter the canyon.

“Don’t go into the creek,” he said.

One company, Alpin Raft, a competitor to Adventure World, cancelled their canyoning trip. “There was no question,” said Heinz Loosli, Alpin Raft’s manager.

But two senior staff from Adventure World arrived. They gave the go-ahead for the Adventure World groups to descend into the canyon.

Investigation and Trial

After the incident, Swiss police began an investigation. Their investigative report concluded the company proceeded with the trip despite a breaking thunderstorm.

The report said that—contrary to the company’s claim that the flash flood was “entirely unforeseeable” and unavoidable—flash floods in the gorge were far from unpredictable, and occurred regularly in the canyon. The report noted flash floods in the canyon were “a well-known phenomenon.”

The police charged eight Adventure World personnel—three owners, two operations managers, and three guides—with manslaughter through culpable negligence.

They were charged with ignoring storm warnings, not having established safety procedures, and providing inadequate supervision and guide training.

A 2001 trial found that the company did not have written safety guidelines. It also found that the guides were not given sufficient instruction regarding local weather conditions.

Six employees were convicted of negligent manslaughter, for allowing the canyoning expedition to continue despite poor weather. The court said the directors were also guilty because they failed to require a risk assessment. Two guides, who the judge said were not responsible for making trip cancellation decisions, were acquitted.

Defendants had faced up to a year in prison, but the prosecutor had only asked for suspended sentences. The three directors were given five-month suspended prison sentences and were fined 7,500 Swiss francs (USD ~4,500). Other defendants were given shorter suspended sentences and smaller fines.

Adventure World Continues—But Not For Long

Just ten months after the drowning incident, disaster struck at Adventure World again. A 22 year old tourist from the USA plunged to his death on a bungee jump operated by the company, after he was attached to a bungee jump cord that was too long, and slammed into the ground.

Two Adventure World employees were convicted of negligent manslaughter, fined $580 each, and given five-month suspended sentences as a result.

Adventure World immediately ceased operations, and declared bankruptcy.

A Voluntary Safety Standard Emerges

Switzerland has a reputation for safety. But the incidents—and the lack of adventure safety standards, voluntary or otherwise—led to questions about Switzerland’s commitment to safety in adventure activities.

Some said that no changes were needed. Adventure-seekers must accept the inherent risk of adventure sports, the opinion went.

Others called for safety regulations to apply to high-risk adventures.

The Swiss authorities, however, were reluctant to act. They preferred private businesses to manage risks of their own activities. “The federal government didn’t want to have to do anything with it,” recalled Markus Fuller, an official with Switzerland’s Federal Office of Sport.

With establishment of compulsory requirements by the Swiss parliament stalled, a voluntary nation-wide safety certification called ‘Safety In Adventures’ was formed in 2000.

The development of the voluntary scheme was headed by officials in canton Bern, where the Saxetenbach incident occurred, and was supported by the Federal Office of Sport (Bundesamt für Sport, BASPO), the Swiss Outdoor Association and the Swiss Council for Accident Prevention (Beratungsstelle für Unfallverhütung, BFU).

The requirements to receive the Safety In Adventures mark included:

- Employees must be trained, experienced and possess appropriate personal aptitudes.

- Equipment must guarantee the maximum safety to users.

- All activities should be planned out, and action plans identified for emergency situations.

- Self-testing and regular evaluation of the conditions for safety are required.

- Third parties involved in any activity should meet the same requirements.

- All checks and assessments must be recorded.

But adventure companies didn’t feel that certification would bring them more business. So not many did the work to gain the Safety in Adventures certification.

BASPO, the Swiss Outdoor Association and BFU supported the development of Safety in Adventures.

High-Risk Adventure Activities Law

The Swiss government passed the Federal Act on Mountain Guides and Organisers of other High-Risk Activities in 2010, which went into effect in 2013.

The Act applies to commercially-offered high-risk activities in mountainous or rocky terrain, and in or around rivers and streams, where there is a risk of slipping or falling, or an increased risk due to rising water levels, falling rock, falling ice, or avalanche, and where special knowledge or safety precautions are required.

It governs mountain guides and snow sports instructors, canyoning, rafting, and bungee jumping.

Activity providers must:

- Alert clients to dangers

- Assess the capabilities of clients

- Manage equipment appropriately

- Evaluate weather conditions

- Ensure staff are adequately qualified

- Ensure a sufficient number of staff are available

- Show environmental consideration

Activity providers must obtain a license and insurance, and are subject to fines for not following requirements.

High-Risk Adventure Activities Regulations

In 2012, the Swiss government passed the Ordinance on Mountain Guides and Organisers of other High-Risk Activities (High-Risk Activities Ordinance), which came into force in 2014.

The regulation covered the same individuals as the Act, as well as mountain guide aspirants, climbing instructors, and mountain leaders. It applied to anyone making more than 2300 Swiss francs (about USD 2500) a year.

The ordinance required a license for:

- Mountaineering

- Advanced alpine hiking

- Ski and snowboard touring

- Advanced snowshoe touring

- Advanced off-piste skiing

- Via ferrata

- Ice climbing

- Multi-pitch rock climbing

- Canyoning

- Whitewater sports on Class III water and above

- Bungee jumping

The regulation described requirements for individuals to obtain a license. A common requirement is holding the relevant Federal PET (Professional Education & Training) Diploma, a credential comparable to a relevant vocational/community college degree in the USA, or a Technical and Further Education (TAFE) certificate such as a Cert IV in Outdoor Leadership in Australia, or a diploma from France’s National School of Skiing and Mountaineering (ENSA).

Equivalent qualifications, for example a mountain guide certification from the IFMGA, or a mountain leader qualification from the UIMLA, are accepted.

Businesses were required to be certified, too. Businesses were required to have a Safety Management System (SMS) meeting the following requirements:

- It provides for a safety assessment of activities offered, on the basis of measurable safety objectives.

- The SMS covers all activities offered.

- The SMS contains training requirements and guidelines to ensure the requirements are implemented.

- Cooperating parties are also licensed, or follow the business’s SMS.

- Certification is based on written documents such as the SMS handbook and on an annual audit of actual practice.

- Defects identified in audits are remedied in a set period of time.

A registry of licensees is published online.

Insurance coverage must be at least 5 million Swiss francs (about USD 5.5 million).

An Update to the Ordinance

In 2019, the Swiss government passed an updated Ordinance on Mountain Guides and Organisers of other High-Risk Activities (High-Risk Activities Ordinance), which went into force that same year, and which replaced the 2012 Ordinance.

The update eliminated the CHF 2300 threshold, requiring operators to have a license from the first franc earned, although certain nonprofits with their own safety procedures are exempted.

The six-point Safety Management System requirement was eliminated. The Safety in Adventures Foundation, which managed the standards regime, was dissolved.

The new certification standards are the ISO standards regarding adventure tourism:

- 21101:2014 Adventure tourism – Safety management systems – Requirements

- 21103:2014 Adventure tourism – Information for participants

- ISO/TR 21102:2013 Adventure tourism – Leaders – Personnel competence

These ISO standards did not exist when the original law was created.

A major audit occurs every three years, with a small annual audit in between. Passing the audit results in certification, which can be used to obtain a cantonal license.

Businesses must use specific risk analysis templates (for example, this canyoning risk assessment template) and meet the objective of fewer than five deaths per 10 million hours of activity.

New Agencies Managing Outdoor and Adventure Safety

With the dissolution of Safety in Adventures, its duties in managing safety in outdoor and adventure activities were passed to the Federal Office of Sport (BASPO) along with the Swiss Council for Accident Prevention (BFU).

BASPO and BFU now oversee the standards conformance audit process. They will also be responsible for grappling with how the global climate crisis is increasing outdoor safety risks, including in alpine areas.

Two private companies were approved by BASPO to conduct audits and issue certifications: SGS (Société Générale de Surveillance), a giant global certifying business, and EdelCert, a small Switzerland-based certifying company.

Is a Positive Safety Record Evidence of Good Risk Management?

Following the mass drowning in July 1999, one of Adventure World’s co-founders said, “We’ve had over 100,000 clients in the past six years, and up until this accident, a broken leg was the most serious injury.”

In May 2000, near the base of the majestic Jungfrau, a half-hour’s drive from Saxeten, Matthew Coleman boarded a gondola to bungee jump off the car mid-cable. The gondola stops for bungee jumping in two places, one 100 meters above the ground, the other 180 meters high. The bungee jump operators, employees of Adventure World, carried a short elastic cord, marked in green, for the lower-elevation jump, and a long cord, marked in red, for the higher jump.

The gondola stopped at the lower-elevation jump site. Adventure World staff mistakenly attached Matthew to the long cord, and he jumped, hitting the ground next to a parking lot. He died instantly.

Adventure World had operated bungee jumps since 1992, its first year in operation, without a single accident.

The gondola operator said the cable car had been used since 1994 for thousands of jumps, without incident.

But in neither tragedy did past performance accurately illustrate the safety culture deficits and risk management shortcuts that critics said were part of Adventure World’s way of doing business.

Outdoor Adventure Safety Regulations Across Europe

Switzerland is not the only European nation to establish outdoor adventure safety requirements.

Mountain guiding, which exposes clients to substantial risks, is regulated across Europe. Mountain guides in France, Italy, Austria, Slovenia, and Slovakia, as well as in Switzerland, must hold recognized mountain guide credentials such as the national mountain guide diploma or IFGMA card, and be registered with the national authorities or governing body.

Finland established outdoor adventure safety standards, which were incorporated into a national consumer safety law and safety document decree.

Following a sea kayaking tragedy in the south of England, the UK created an adventure activity licensing system and regulations. (The UK government initially resisted creating legislation, instead favoring a continuation of a voluntary system, but relented, under pressure from parents and others.)

The Eastern European nation of Georgia is currently developing an outdoor adventure safety law and related regulations.

Adventure Safety Laws Under Attack

Within a few years of Switzerland’s landmark adventure safety law coming into force, an attempt to dismantle its safety requirements arose.

In 2016, the Swiss government, in an effort to cut costs (some CHF 150,000), proposed to revoke the law. Protests arose, however, and the government dropped its plan.

This attempt to repeal the national adventure safety law—with survivors still traumatized, family members in mourning, and the body of one victim, 24 year old Alisa Redmond, still not found—is not an isolated event.

The 1995 outdoor adventure safety law passed in the UK following a quadruple drowning on a poorly-run children’s kayaking trip came under attack in 2010. That year, the UK’s conservative government proposed to abolish the law, which has served as a global role model for adventure safety. The government’s plan was dropped after the move was widely criticized, including by parents of children who drowned on the trip.

But recently the idea resurfaced, and efforts to revoke the landmark legislation are currently advancing.

It remains to be seen if the family members of those who died at the hands of outdoor businesses who cut safety corners, joined by others who support requiring good safety practices for outdoor adventures, will be successful in protecting outdoor adventure participants from efforts to abolish safety rules.

The Future of Outdoor Adventure in Switzerland

Switzerland remains an extraordinarily attractive destination for outdoor adventure. Its glacier-carved Alps, sparkling mountain lakes, and picturesque valleys dotted with villages bring outdoors-lovers of all kinds. And its reputation for safety and quality adds to Switzerland’s considerable appeal.

Following the tragedy in Saxetenbach Gorge, Switzerland quickly responded with legislation and regulation to help uphold its reputation for well-organized outdoor sports meeting high safety standards.

The Swiss Confederation joins a tiny handful of other nations—New Zealand and the UK among them—with a dedicated outdoor adventure safety law, and the benefits that a level playing field of safety requirements brings.

When the muddy, churning avalanche of water came roaring down the Saxetenbach gorge one July afternoon, a wall of black water smashed people’s bodies against rocks, and tumbled them downriver, where they flushed into Lake Brienz. A jogger passing by saw bodies floating in the lake, and raised the alarm.

Injuries to the victims were so severe as to make the bodies unrecognizable. Interpol sent police to victims’ homes to obtain DNA samples to aid in identification. Grieving family members flying to Switzerland were asked to bring dental records of their loved ones.

The tragedy was not an unpredictable surprise brought about by an unforeseeable flash flood. Instead, flash floods in canyons happen regularly, in canyons around the world, and investigators determined the incident was brought about by a company’s lax safety culture and poor risk management practices—in a setting where an absence of adventure safety regulations created a space for companies to systematically chip away at safety procedures, in pursuit of business growth.

“This accident didn’t happen on the 27th of July,” said Heinz Loosli, the manager of Alpin Raft. “It was created over years.”

When the Swiss government created a national adventure safety law in 2010, backed up two years later by detailed outdoor safety regulations, it took an important step in helping prevent future tragedies.

Today, Switzerland’s outdoor adventure sector sees millions of visitors, who go canyoning, skiing, rafting, paragliding, mountain biking, bungee jumping, hiking and ballooning across the idyllic alpine landscape that is Switzerland.

The memorable experiences and good safety outcomes these adventurers enjoy are made possible in part by Swiss safety laws.

And they’re made possible as well by the adventure program providers committed to excellence in risk management, who uphold the promise that Adventure World had posted on their website two days after the Saxetenbach tragedy:

”Safety,” it said, ”is our highest priority in all activities.”