Managing Provider Relationships for Safety in Travel, Wilderness, Experiential and Adventure Programs

An International Misadventure

The prestigious private school wanted something great. The school wished to offer a memorable, unique educational experience that their students would love. And they wanted an exciting and compelling program that would attract the interest of the parents of prospective students, and drive enrollment.

But what will students get excited about—and will look good in marketing materials? They decided: we’re going to offer an outdoor adventure program.

The school, however, didn’t have expertise in running outdoor trips. So they turned to a local vendor that advertised experiential education programs. They asked the provider: what can you do for us?

The outdoor program provider responded: How about an international adventure in the mountains and jungle of South America?

And so a group of students from the school flew to South America and began their expedition.

But it didn’t go as planned.

The group backpacked through the Amazon jungle. They explored the alpine wonders of the Andes. The vendor, though, had limited experience in leading trips. In fact, they had never before organized an international expedition.

High in the Andes, the group began running out of food. Desperate for supplies, the group illegally crossed an international border. The students entered remote villages, begging the impoverished inhabitants for food to eat.

They ended up finding food. Everyone survived the expedition. But students came back up to 20 pounds lighter. Some had contracted the life-threatening disease malaria.

The elite private school was happy that all the students made it back alive. And, certainly, the trip was “unique” and “memorable.” But the school was not pleased with how the provider organized the trip. The school’s administrators never asked the provider to lead an international expedition for their students again.

Introduction & Summary

What are the lessons learned from this ill-fated expedition? We’ll explore a variety of points about safety-related aspects of working with subcontractors in the outdoor context, which we’ll summarize here.

- Subcontractors can provide valuable benefits and opportunities, including risk transfer from an organization.

- Subcontractors can also bring risk, unless the subcontracting process is carefully managed.

- The subcontractor-contractee relationship should be structured to be legally valid.

- A written contractor agreement should exist and include risk transfer elements.

- The contractor should verifiably hold appropriate insurance.

- Potential contractors should be thoroughly evaluated for suitability.

- Contractor assessment should occur before, during, and after the period of service.

- Program participants should be advised of the use of subcontractors.

- Liability transfer may be limited for inherently dangerous activities.

- Specific legal advice should be sought from a qualified attorney.

- Subcontractor-related risk management falls within a larger risk management system.

- Managing specific risks in risk domains, and employing risk management instruments, supports positive safety outcomes.

- Opportunities to learn more are available.

Why Use Subcontractors?

Subcontractors may not always operate to safety and quality standards to which the organization hiring them expects them to conform. And an organization’s management generally has less awareness of and control over how a subcontractor operates, compared to how employees carry out their work. Why then, use subcontractors?

Subcontractors are also known as providers, vendors or contractors. We’ll use those terms interchangeably here. But whatever the name, the use of subcontractors may bring undeniable benefits.

An organization may find it more practical to contract with a sailing trip provider than to buy their own ship.

Access Knowledge and Skills

Subcontractors often bring skills and knowledge that the organization retaining them simply doesn’t have. A school may not be expert in whitewater rafting—but the appropriate provider for an adventurous, rapids-filled river raft trip should be.

Access Equipment or Facilities

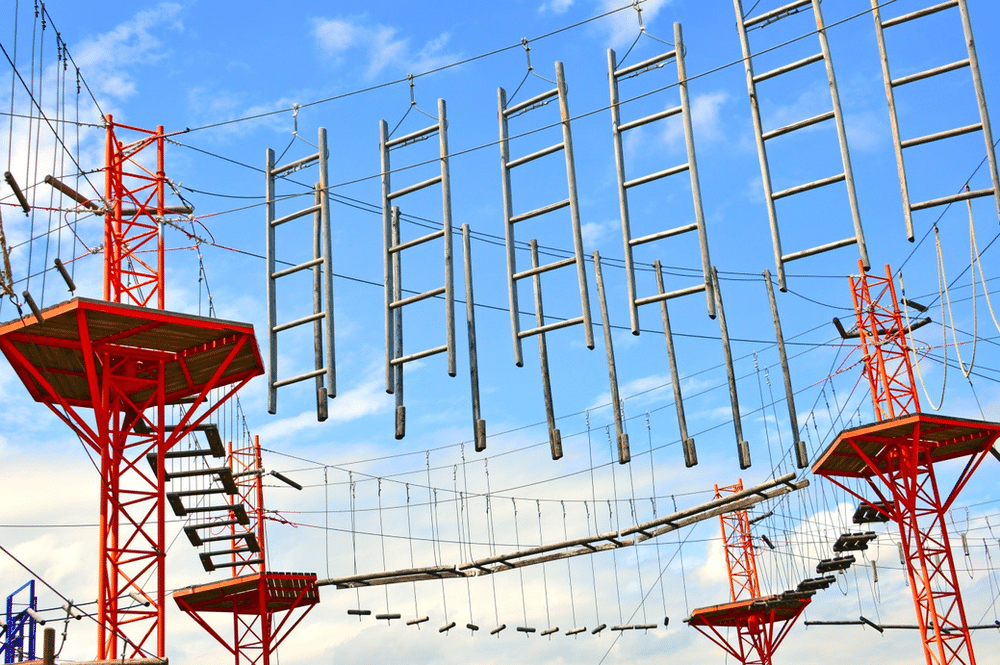

Subcontractors may have equipment or facilities that that others don’t have, or don’t find cost-effective to own. A high ropes challenge course, for instance, is a major investment. It’s one that often makes financial sense only an organization specializing in team-building adventures, and which can keep the ropes course busy year-round.

Potentially Transfer Risk

And finally, strategic use of subcontractors can transfer risk away from an organization. Transportation, for example, is a high-risk activity. Hiring a carefully selected bus company with professional drivers, well-maintained vehicles, and a skilled fleet management staff may reduce both the potential for motor vehicle accidents, and the legal liability if an accident should occur.

Best Practices for Risk Management with Subcontractor Relationships

Subcontractors can be useful. But they also bring risks. How can one maximize the benefits of using specialist providers, while minimizing the potential for liability?

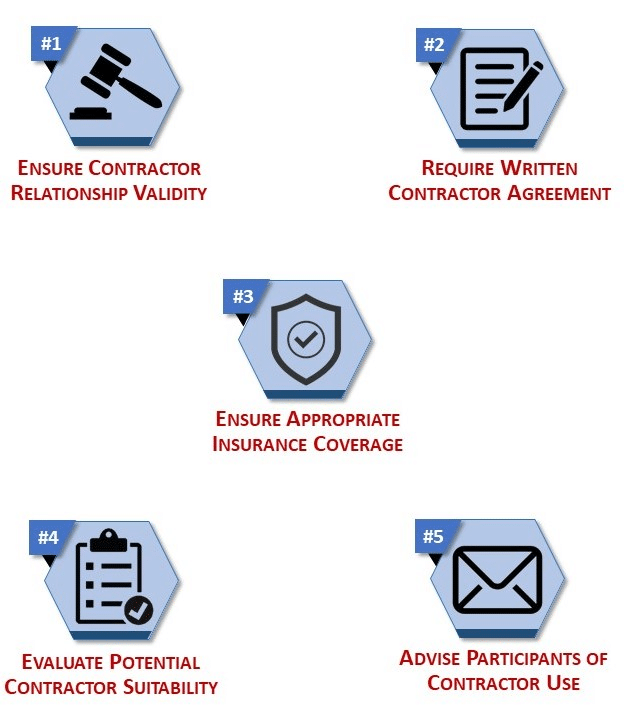

There are five practices than can help reduce risks associated with hiring subcontractors to perform work. They’re listed below, and we’ll explore each one in detail.

- Ensure the Contractor Relationship is Valid

- Require Written Contractor Agreement

- Ensure Appropriate Insurance Coverage

- Evaluate Potential Contractors for Suitability

- Advise Participants of Contractor Use

Best practices for managing risks of subcontractor relationships

Ensure the Contractor Relationship Is Valid

The relationship between the organization, and the contractor it hires, must legitimately be a contractee-contractor relationship. It must not be, in actuality, an employee-employer relationship.

This means that the contractor must control the manner in which they perform their work.

In some jurisdiction, additional steps can be taken to demonstrate a valid contractor relationship. For example, it may be helpful to have a written contract setting a price and a timeline for the specific work to be done.

The contract may also make clear that the work is not subject to termination without conditions (such as no payment for premature termination), as is commonly seen in at-will employment agreements.

Note that merely agreeing in writing that a relationship is an independent contractor relationship does not make it so. Instead, circumstances such as described above must be in place.

If the contractor relationship is not valid, the arrangement can be treated as an employer-employee relationship, which can increase the liability of the hiring organization in case of an incident.

Require Written Contractor Agreement

A written agreement signed by the hiring organization and the contractor can establish terms that help protect the organization that retains the contractor.

The agreement should clearly state the independent contractor relationship. As noted above, however, additional elements should be in place for the relationship to be considered valid in a court of law.

The contractor should agree to release the organization from liability from losses experienced by the contractor. If the contractor’s kayak is lost in a storm, the hiring organization is not responsible for the loss.

The agreement should specify that the contractor agrees to indemnify the hiring organization. This means that the contractor accepts responsibility for paying costs resulting from their activities.

For instance, suppose the contractor makes a mistake and a participant is injured. The participant sues the contractor and the hiring organization. The contractor would be liable to reimburse for expenses the organization incurs as a result of the suit.

A provider’s elephant trek can be fun and relatively safe—but a written agreement limiting risk should still be signed.

Ensure Appropriate Insurance Coverage

The contractor should be required to carry suitable liability insurance, and provide evidence of that coverage.

The contractor should provide the hiring organization with a Certificate of Insurance (COI) showing their policy, its effective dates, and policy limits.

The contractor’s insurance policy should, if possible, name the hiring organization as “additional insured.” With many policies, this is easily done, and at no additional cost.

The policy, including any endorsements, should cover the work that the contractor may perform. No exclusions to coverage should exist that might open gaps in coverage.

The policy limits—how much money is to be paid out per occurrence, and in the aggregate—must be reasonably sufficient to cover potential claims. The hiring organization’s insurance specialist or broker may be able to advise on minimum limits, should there be any question.

Evaluate Potential Contractors for Suitability

The independent school that hired a provider to take their pupils to explore the wilds of South American jungles and mountains had not completed a searching assessment.

The trip occurred years ago. But what the school didn’t know at the time was that the outdoor program provider, formed just two years previously, had very limited risk management infrastructure—or anything else.

The provider’s four core staff were recent college graduates with limited funding and experience. They had all been living together in a mobile home, dumpster diving for groceries and subsisting on government food aid, while trying to develop program offerings and find clients to pay them to lead trips.

In the words of one of those four founders, the provider’s staff at the time “were stoned, and broke, and needed something to do.”

In another instance, a school hired a contractor to provide swimming activities, not knowing that previously, four children had drowned on the contractor’s premises, and apparently not bothering to check the provider’s safety record. On the first day of the outdoor education experience, one of the school’s learners drowned.

Evaluate Before, During and After Service

Any potential provider should be assessed, before an offer of work is provided, for how well-suited they are to meet the organization’s quality and safety requirements.

The provider should also be evaluated during the course of the contract, to help ensure that acceptable performance continues.

And following the completion of the agreed-upon work, an analysis should be conducted to determine whether the work performed met standards, and under what conditions the contractor would be eligible for re-hire.

To what standards should the subcontractor be held? In general, a subcontractor’s risk management systems should generally meet the same high standards to which the contracting organization holds itself.

Methods of Pre-Retention Evaluation

The most reliable evaluation of a subcontractor an organization is considering retaining gathers information from multiple sources. These may include:

I. Provider questionnaire

II. Professional references

III. Document review

IV. Facilities/equipment assessment

We’ll address each of these four evaluation components, below.

I. Questionnaire

A questionnaire is a useful approach for getting specific, written information than can help determine prospective contractor suitability for the work to be done.

The questionnaire may ask the potential contractor to describe:

- Activities and Program Areas: the level of experience the provider has with the activity and activity area (measured, for example, by length of time)

- Equipment:

- Standards for equipment use, care, and management (including selection, inspection, maintenance, repair, storage, and retirement) for the equipment that will be used with the activities under consideration

- Safety and emergency response equipment provided

- Staff: qualifications for staff, including required experience, skills, training, certifications (medical, technical outdoor skills, licenses, or other) and background check results

II. Professional References

It’s a good idea to hear from several references about how the potential contractor may or may not be suited to perform the work to be done. For example, other schools who hired the same travel or adventure provider could describe their experience with the provider. Evidence should be retained to show that reference checks were completed thoroughly.

III. Document Review

In addition to completing a questionnaire describing experience, equipment, and staff considerations, the contractor under consideration may also be asked to provide:

- Copies of any authorizations (including permits and licenses), accreditations, and certifications relevant to the activities and areas under consideration

- Summary of safety record for last 10 years, including incidents, insurance claims and legal actions

- Summary of any safety review findings

- Copy of emergency plan

- If providing transportation: transportation safety policies, addressing topics such as vehicles (including management standards in the equipment section of the questionnaire above), licensing, operator testing and training, motor vehicle record checks, vehicle operating procedures

- List of sub-subcontractors that may be used by the subcontractor, and the above information for each sub-subcontractor

The quality of the prospective contractor’s emergency procedures should be evaluated.

IV. Physical Facilities/Equipment Assessment

In some cases, an in-person inspection of a potential contractor’s physical facilities or equipment may be important in the assessment process.

For example, an on-site walk-through of overnight accommodations may provide useful information about safety and security.

An outdoor program provider’s activity facilities—such as a climbing wall, sailing ship or high ropes challenge course—may also be best evaluated by including an in-person inspection.

A contractor’s challenge course or climbing wall should be assessed before use, including permits, inspections, standards conformity, safety record, maintenance, staff qualifications, and more.

Overcoming Reluctance to Share Confidential Information

Not all contractors will be eager to share internal information, such as safety audit findings, insurance claim history, and detailed proprietary procedures.

It may be useful to note that responses are required for compliance with the organization’s safety standards or insurer requirements, assuming that is the case.

An organization requesting information can make clear that its detailed inquiry is not intended to be invasive. It is, instead, simply an effort to conduct due diligence and access convincing evidence that the organization’s risk management requirements will be met.

Making an offer to review internal information at the prospective provider’s office, where the information stays in the potential contractor’s direct control, may help.

And agreeing in writing to hold all submitted materials in strict confidence may also help providers feel comfortable in releasing internal information.

When an Organization Is Unqualified to Evaluate a Provider

A school wishes to hire a provider to take youth on a multi-day sailing expedition. But school staff don’t know how to sail, what relevant sailing standards and safety regulations may exist, or what questions to ask of sailing trip providers.

Sometimes a bit of research can help an organization learn enough to be able to ask the right questions and conduct a meaningful evaluation.

In other cases, a qualified third party might be brought in to perform an evaluation and provide a report.

Limitations of Risk Assessment Spreadsheets

In some parts of the world, a common practice is to request a “risk assessment” spreadsheet from potential outdoor program providers. This document is used to evaluate the quality of the provider’s risk management system.

Risk assessment spreadsheets typically feature a lengthy list of potential hazards or risks—youth getting lost in the airport during travel, severe weather, road traffic, boat capsize, etc.

Sometimes, these hazards or risks are ranked in terms of severity and probability, for instance on a 1-5 scale.

For each risk, then, control measures are listed. Use a buddy system and close supervision in airports to prevent left-behind children. Check weather reports before heading out. For planned travel abroad to a region suddenly experiencing severe civil unrest: stay home instead.

This can be useful—up to a point. Risk assessment spreadsheets work well for identifying certain reasonably predictable hazards—this cave is prone to flooding; lightning storms are common in summer afternoons.

However, advances in safety science tell us that major incidents often occur due to a constellation of risk factors that interact in inherently difficult-to-predict ways.

For example, an outdoor program with a detailed Risk Assessment and Management System (RAMS) and multiple safety procedures experienced a multiple fatality event during a canyon flood. A wide variety of issues—from radio deficiencies, poor training, and a deficient safety culture, to weather service failures and lack of regulation—were cited as contributing factors.

Another organization that prided itself on a strong culture of safety and significant risk management investments sent a child to the hospital after she crashed into a massive obstacle at the bottom of a high-speed zipline. Contributing factors included staff turnover, equipment misuse, communication issues, and ropes course installer problems.

The aviation and healthcare sectors have invested heavily in risk assessments and many other risk management techniques. And yet in these and other industries, significant incidents such as airplane crashes and wrong-limb amputations continue to occur. And identifying the causes, let alone establishing effective fixes for them, can at times be difficult or impossible.

Safety researchers therefore suggest that the current practice of heavy use of risk assessments as a primary tool in evaluating and addressing risks is not compatible with the current best thinking in how accidents actually occur.

Risk assessments do have a place. However, they should not be relied upon as evidence that a potential contractor has a comprehensive, high-quality risk management system in place.

Instead, evidence of systems-informed risk management approaches should be evaluated in order to have reasonable confidence that an effective risk management system has been established.

Risk Assessments can be a limited part of quality risk management, but should not be overly relied upon.

Avoiding Claims of “Negligent Selection”

An organization that fails to appropriately evaluate potential subcontractors before making a hiring decision can be held liable for “negligent selection.” This is the failure to conduct due diligence regarding a potential subcontractor. It’s similar to negligent hiring of employees, but in the contractor context.

Negligent selection can bring significant penalty in case of loss. A case study (outside of the outdoor context) illustrates this.

In the state of Florida in the USA, a landlord hired a handyman to install cabinets in a rental property. The cabinets were incorrectly installed, and fell on the tenant.

The owner did not check if the handyman was licensed. The owner also did not inquire about the contractor’s qualifications. And the owner did not check any references.

The handyman was hired on the basis of being observed to be in the neighborhood with some cabinets in a truck. There was no contract. The owner could not even recall the person’s name (or if he operated under any business name).

The tenant sued (Suarez v. Gonzalez, 820 So. 2d 342, (Fla. 4th DCA 2002)) and won over US $2.7 million from the owner.

The presence of furniture in a truck does give evidence of a qualified cabinet installer.

Contractor Evaluation During Service

An organization has carefully selected its chosen provider. But the responsibility to assess suitability doesn’t end there. The organization should also evaluate the contractor during the course of service.

Suppose a provider is hired to lead school pupils on a whitewater rafting adventure and service learning trip to Sri Lanka. Teachers from the school accompany as chaperones. Those teachers should continually observe and evaluate the provider. If questions or concerns arise, the teachers should take the steps necessary to see that they are addressed.

Some contractors may conduct activities on an ongoing basis. A transportation provider, for instance, might regularly carry participants in vans or busses to outdoor activity locations. Periodically, for instance once a year, a formal assessment of continued contractor suitability may be conducted, using the questionnaire and document review structure described above.

Contractor Evaluation After Service

The conclusion of a provider’s service is another appropriate point to evaluate the provider’s safety performance.

An organization hiring a provider might incorporate a contractor evaluation into its formal program evaluation process held at the conclusion of the program. For example, if the school chaperones on the Sri Lanka expedition described above complete a written post-trip report, a section can be devoted to contractor performance.

Similarly, if participants in an outdoor activity are asked to evaluate their experience, obtaining feedback on their impression of the contractor can also be useful.

The contractor themselves may also be asked to evaluate and report on their activities. This could take forms including verbal conversations, written reviews, sharing of incident reports, or otherwise.

Rafting on the Kelani River in Sri Lanka is a popular activity provided by local contractors.

Advise Participants of Contractor Use

In addition to ensuring a valid contractee-contractor relationship, instituting a written agreement, obtaining evidence of suitable insurance, and evaluating suitability of potential contractors, one element of good practice remains.

This is informing program participants that one or more contractors may be employed during the course of their experience.

A person who signs up for an outdoor adventure provided by a well-reputed organization might reasonably expect that the experience be conducted by that organization. The potential for liability exists, then if the participant experiences injury or other harm at the hands of a contractor whom they did not realize would be present, and whose safety record they did not have the opportunity to investigate in advance.

If an organization chooses to use subcontractors, the organization should make clear to participants—and their adult parents/guardians if enrollees are minors—that contractors will be used for certain activities. Which activities will be conducted by contractors should be made clear.

The organization should communicate that, while contractors have been carefully selected, the organization is not responsible for the contractors’ actions.

Potential participants should be apprised of the presence of contractors well in advance of the program, so that they can gather additional information, and, if they choose, decline to participate, without significant cost or inconvenience to themselves.

Participants should acknowledge and accept the risks of engaging with contractors, and release the organization from negligence on the part of the contractor.

Limits of Risk Transfer to Contractors

The steps described above–regarding contractor relationship, written agreement, insurance, evaluation, and participant communications–can help reduce the risk an organization faces in providing outdoor activities to participants.

One element of this risk management system is transferring risk from the contractee to the contracted provider. However, there are limits to this strategy.

In some jurisdictions, organizations may not be able to eliminate their liability for work done by a contractor, if that work is inherently dangerous.

For example, in the state of Michigan in the USA, a contractor was hired to log timber from the landowner’s property. A tree fell on the contractor’s employee, crushing their leg.

The landowner was found liable for the injury of the contractor’s employee (DeShambo v. Nielsen, 471 Mich. 27, 684 N.W.2d 332 Mich., 2004), on the basis that logging is an inherently dangerous activity.

Similarly, a school might hire a provider to lead whitewater kayaking activities or provide service learning experiences in remote villages in a low-income country with limited emergency medical care and transportation.

This activity could be considered high-risk in nature, due to the type of activity and limited access to emergency services.

If an incident occurs, the school, along with the contractor, could potentially face liability for the incident.

Risk transfer may be limited in higher-risk activities like white-water kayaking.

Consult a Qualified Attorney

Legal circumstances vary widely by jurisdiction. The information here should not be considered legal advice. Organizations should consult a qualified attorney familiar with their activities and areas of operation for guidance specific to their situation.

Contractor Risk Management, In Context

Risk Domains

Subcontractors can be used to provide experiences that an organization finds inconvenient or impractical to provide itself.

This may, in some cases, reduce risks to an organization, by transferring that risk to a contractor.

In addition, we’ve outlined steps above that explore how particular risks associated with working with contractors can be mitigated.

But risk management considerations related to subcontractor use exist within a larger milieu. It may be useful to understand how subcontractor-related risk management fits in the larger context of risk management for outdoor and experiential programs in general.

Let’s take a brief look.

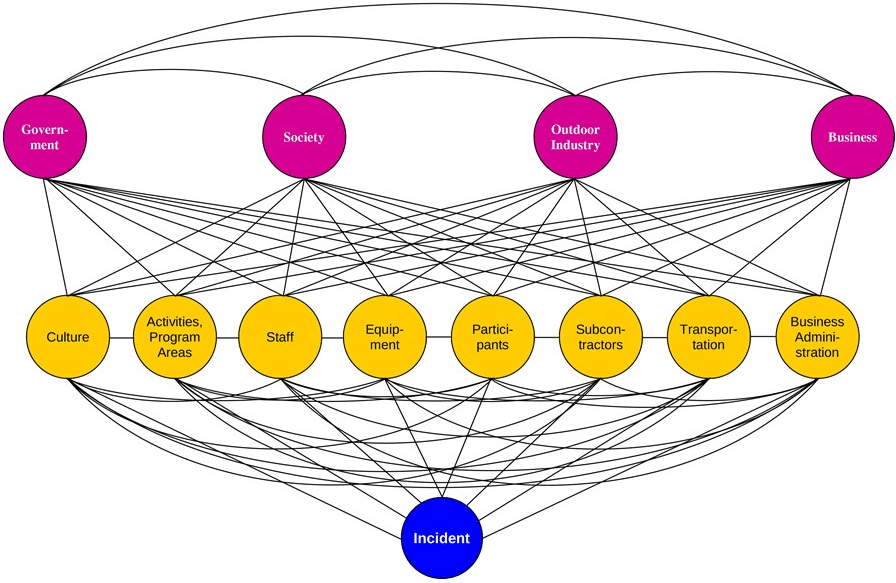

When an accident occurs, it typically happens because of risk factors found in one—or, usually, more than one—risk domain. These risk domains, or “risk reservoirs,” categories of where risk can be found, are: Organizational Culture, Activities and Program Areas, Staff, Equipment, Participants, Subcontractors, Transportation, and Business Administration.

These are “direct risk domains,” where factors that may directly lead to an incident reside.

In addition, there are underlying risk domains. These are areas in which can be found factors that indirectly influence the probability and severity of incidents. The underlying risk domains are: Government, Society, Outdoor Industry, and Business.

Risks found in direct risk domains (yellow) and underlying risk domains (fuchsia) combine and lead to incidents.

We can see that the domain of subcontractors, or providers, is one of eight direct risk domains.

But systems theory tells us that things are connected, and in ways we can’t always see or understand.

Therefore, in order to have excellence in risk management with respect to subcontractors, we also need high-quality risk management in other domains.

For instance, a provider may be hired to conduct an outdoor adventure activity for participants. But if the safety culture of the organization that hired the subcontractor is very poor, the contractor may be pushed to bend its own safety rules or otherwise increase risks.

Similarly, an adventure provider leading an outdoor experience for school students accompanied by adult school chaperones may be unable to prevent an incident on the trip if the school chaperones willfully engage in unsafe behavior.

Finally, if the provider operates in a region where the government fails to establish and enforce good safety regulations, or provide adequate emergency services, the probability and severity of incidents may increase even for a prudent and well-qualified provider.

Here we see where domains of Culture, Staff and Government influence safety outcomes on outdoor programs provided by contractors.

Therefore, a thoughtful organization will institute and maintain policies, procedures, values and systems to mitigate all reasonably foreseeable risks in all risk domains, to the extent practicable.

Risk Management Instruments

An organization is well-served to identify any appreciable risks it may encounter in the risk domains described above, and employ specific policies, procedures, values and systems to manage those risks it has identified.

For instance, an outdoor program could recognize that individuals in a certain region of Africa have a level of immunity to malaria, due to having lived in a malaria-endemic region their whole life. They may, as a consequence, not take malaria as seriously as those from other areas might. This means they might not recommend strong malaria prevention activities, or advocate for effective malaria treatment in the case of exposure, increasing risks to foreigners seeking outdoor adventures in the region.

Therefore, the organization advertising trips to the region, and hiring contractors to provide those experiences, might establish strict policies around carrying malaria medication, retaining an outside medical consulting service to complement the advice of local medical care providers, and pre-arranging for access to airborne medical evacuation to be used as needed.

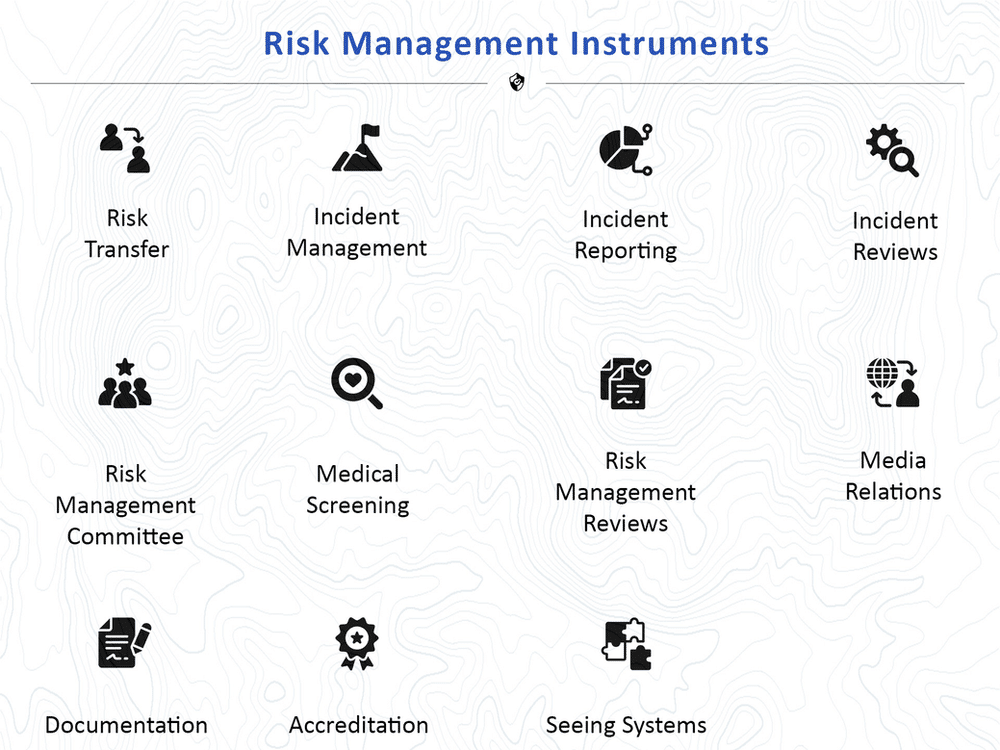

In addition to employing specific policies, procedures, values and systems to manage specific risks, broad-reaching risk management instruments can also be employed. These instruments, or tools, can mitigate risks across a broad range of risk domains.

For example, a good insurance policy can insulate an outdoor program from liability stemming from incidents related to equipment, participants, staff, transportation, or any other risk domain.

There are 11 risk management instruments to consider: Risk Transfer, Incident Management, Incident Reporting, Incident Reviews, Risk Management Committee, Medical Screening, Risk Management Reviews, Media Relations, Documentation, Accreditation, and Seeing Systems.

All of these instruments can be employed to support good risk management with respect to subcontractors—and all other risk domains.

For example, we’ve touched upon requiring a contractor to provide evidence of liability insurance, and to indemnify the contractee against losses arising from contractor’s activities. These can be placed under the “Risk Transfer” risk management instrument.

Similarly, requiring a written agreement with a contractor, establishing terms to make clear there is a valid contractor-contractee relationship, can fall under the instrument of “Documentation.”

Evaluating a contractor’s Emergency Response Plan is part of the “Incident Management” instrument; using an accredited provider when available is an application of the “Accreditation” risk management instrument, and so on.

Systems Thinking as a Risk Management Instrument

One of the principles of complex socio-technical systems theory, as discussed above, is that in a complex socio-technical system such as a led outdoor activity, it’s not possible to identify all risks in advance.

Therefore, in applying the “Systems Thinking” instrument, an outdoor program should take steps to ensure that its risk management system will be resilient when confronted with system failures from an unexpected source and at an unknown time.

This resiliency can be fostered by having extra capacity—for instance, having emergency procedures in place, in case the contractor’s emergency response is insufficient.

It can also be fostered by supporting a balance between rules-based safety and the use of individual judgment. This is called “integrated safety management.”

And systems-informed planning tools, such as the “pre-mortem” technique, can help organizations creatively anticipate and reduce the severity of incidents, before they occur.

These systems-informed approaches to outdoor program risk management can help reduce risks when using subcontractors, and in all other aspects of conducting outdoor, adventure, wilderness, travel, and experiential programs.

From a South American Debacle to Success

The provider pivoted from expeditions in the Amazon to experiences closer to home.

When last we heard about the student group which had adventured through the jungles and mountains of South America, they had all returned, more or less safely, to their home country. Despite malnutrition and disease, every student made it home.

The sending school was not impressed with their provider’s performance, however.

The provider continued to provide programs to area schools, and invested heavily in improving their risk management systems.

They became one of the first organizations in the world to complete a rigorous accreditation process as an experiential adventure provider.

They were of the first outdoor education organizations to choose the Wilderness First Responder as the standard medical certification for their instructional and administrative staff.

The provider built a sophisticated safety management system, with extensive plans and documents, including a Risk Management Plan, an Emergency Call Guide, and a plethora of forms, including an Incident Report Form, Course Director’s Accident/Incident report form, Missing Person Report Form, Evacuation Report, and Medical Facility Visit Form.

They turned their focus exclusively to domestic programs. The provider contracted with a professional vendor member of a leading challenge course association to construct a high ropes challenge course not far from the school that had hired them to take their students abroad. The ropes course became additionally accredited under a camp-based accreditation scheme.

The school eventually hired the provider again, to supply team-building ropes course experiences for hundreds of their students. Year after year, the students experienced outdoor adventures and team challenges organized by the provider, with consistently excellent safety outcomes.

The school had grown in its ability to assess providers. And the provider had dramatically improved their management of risk. And the students experiencing the ropes course and team-building challenges had a great time.

In the end, it was a successful experience for all.

The provider found success in running high-quality high ropes challenge course experiences.

Obtain Legal Advice

As was mentioned above: the information here should not be considered legal advice. Organizations should consult with a qualified attorney familiar with their activities and operations, and familiar with the relevant law, for advice specific to the organization’s situation.

Conclusion

The days of hiring poorly equipped novices to lead international wilderness expeditions generally are, thankfully, over.

We now recognize that providers can be of great benefit from programmatic and risk management perspectives—but that best practices in provider selection and management should be followed.

These best practices include:

- Having a legally valid contractor-contractee relationship

- Requiring a written agreement with risk transfer elements

- Ensuring the contractor holds appropriate liability insurance

- Evaluating contractors closely before, during and after service

- Informing participants of contractor use

We recognize that in some jurisdictions, courts will not allow risk to be transferred to a contractor involved in inherently dangerous activities.

And we understand that good subcontractor risk management requires high-quality, comprehensive systems-informed risk management. All identified risks, from any risk domain, should be managed through appropriate policies, procedures, values and systems. Broad-reaching risk management instruments should be employed to reduce risk across multiple risk domains.

And systems-informed approaches such as building in backups and additional capacity, using integrated risk management to balance rule-conformity and adaptability, and employing systems-based strategic planning techniques, support excellence in outdoor safety.

Opportunities to learn more are available, and a qualified attorney should be consulted for specific legal advice.

Learn More

Individuals interested to learn more about contractor engagements, wilderness risk management, travel safety, risk assessments for outdoor adventurous activities, and related topics mentioned above can do so through participating in the Risk Management for Outdoor Programs 40-hour online course by Viristar.

This rigorous class, held over 4 weeks, provides a comprehensive training on outdoor safety standards, risk management best practices, and the most current thinking in safety science applied to experiential and outdoor programs.

The course consists of five video-conference sessions, generally 90 minutes each, one week apart. In between are independent work periods. Here participants engage in online discussion forums, video-based lecture presentations, quizzes, video-based role-play scenarios, and small group projects.

Participants complete a detailed self-assessment of risk management of their own outdoor or experiential program. They draft a Risk Management Plan outline for their organization, and create a strategic plan for improving management of risk in their workplace.

Participants receive a copy of the textbook Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure.