Note: This story contains content which some may find distressing.

Denis Murphy, 56, was a painter and decorator by trade. He had a passion for sport.

The eldest of four children in a close-knit London family, he had moved with his wife into London’s 24-story Grenfell Tower public housing block in 1984.

On June 14, 2017, at 1:25 am, Mr. Murphy put in a 999 call to emergency services, reporting a fire outside his 14th-floor window. He said smoke was entering his apartment. Emergency services reassured him firefighters were on their way.

Firefighters arrived, and found him bent over and coughing, with soot on his face. Because of heavy smoke in the stairway, the rescuers decided not to evacuate Mr. Murphy down the stairs. Instead, they brought him to the 14th floor lobby, where the air was clearer.

As Grenfell Tower continued to burn, fire arrived outside the area where he was sheltering, and asphyxiant gases from combustion increased to a lethal level.

Mr. Murphy lost consciousness, but continued to inhale the asphyxiant gases until, shortly after 4:00 am, his respiration and circulation ceased.

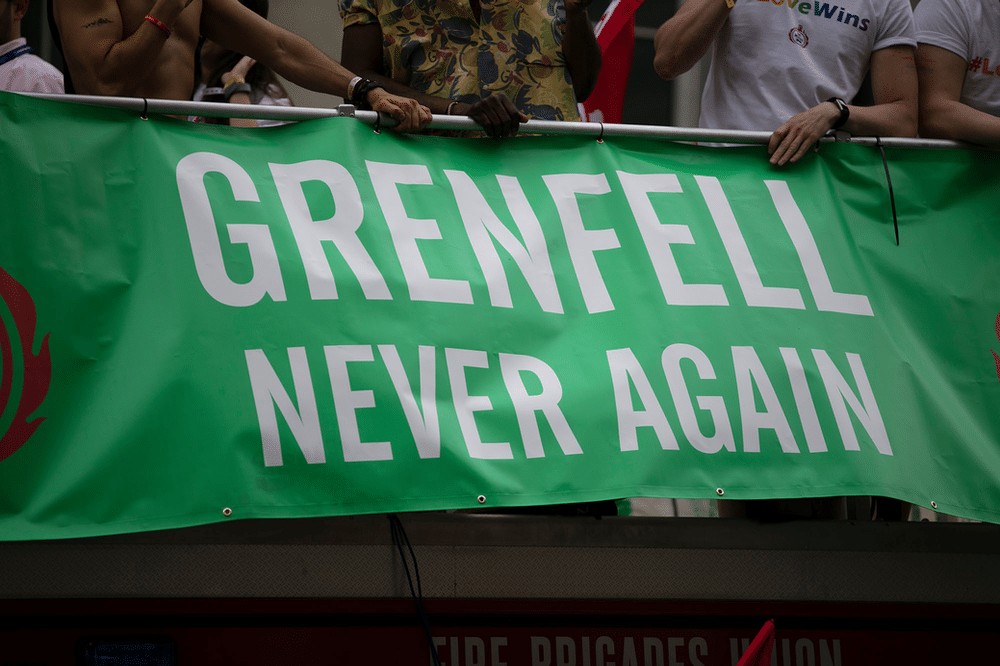

Denis Murphy was one of 72 persons to die in the Grenfell Tower fire.

Grenfell Tower opened in 1974. After a period of decline, a refurbishment of the aging building was scheduled. As part of this process, the external walls of the high-rise residence were covered with highly combustible materials, flammable polyethylene plastic covered by a thin sheet of aluminum.

A fire in a fourth-floor kitchen quickly spread to the outside of the building and raced up to the roof, engulfing the tower in flames.

An Inquiry Panel was convened to investigate the fire. On September 4, the Panel released a 1,671-page report.

The report concluded that the 72 deaths were foreseeable and preventable. The BBC, in reporting on the incident, said this is a story of “corporate deceit, government deregulation drives and a construction industry in a race to the bottom.”

De-regulation

The United Kingdom has had years of anti-regulatory government, and the 1980s were no exception. Margaret Thatcher worked to reduce regulations.

Under her rule, precise rules in regulations were removed. They were replaced with only a description of the desired end result.

In regulations regarding external walls of buildings, the requirement was that the walls must offer “adequate resistance” to fire—but the regulations did not specify what this meant, or how it was to be measured.

A fire safety specialist who testified during the inquiry said this empowered the construction industry to “not really care” about safety as much as they should have.

Multiple Causes

If de-regulation was at the heart of the contributing factors to the tragedy, it was not the only player. The report found unscrupulous manufacturers, dishonest sales practices, and incompetence to be part of the toxic and fatal mix.

The Risk Was Known

In 1999, a 14-story building burned, with building materials of the same level of fire resistance as Grenfell Tower. Observers recommended external wall coverings (cladding) in buildings should be non-combustible.

Government leadership didn’t agree, saying “it would cost millions” to remove combustible cladding. Across the country, combustible cladding—known to be a hazard—remained on buildings.

In 2009, the combustible cladding on another tower block, in south London, burned; six people died.

Again, nothing happened.

De-regulation Prioritized Over Safety

In 2005, yet another building with combustible cladding burned, this time in the Middle East.

Following the conflagration, a UK government official was warned the same flammable materials were being sold in the UK.

But this was a decade of cutting regulation, of fighting against “health and safety gone mad.”

The government official said, “Regulation was a dirty word.”

The government adopted a “one in, one out” policy, where one regulation had to be abolished for every new one. This morphed into a more extreme policy of “one in, three out.”

Meanwhile, the combustible cladding remained.

Manufacturer Deception

The company that made the cladding, Arconic (formerly Alcoa), had received a certificate confirming that its “standard panel” met fire safety standards.

Arconic sold the panels in a flat shape, which met the safety standards. But Arconic also sold panels in a folded shape, which performed spectacularly worse in fire tests.

Misleadingly, Arconic didn’t provide the results of those failed tests on the folded panels, when it applied for the certificate.

The Inquiry Panel report said Arconic “deliberately concealed from the market the true extent of the danger” of using its cladding in high-rises.

Architecture Firm Failures

The architectural firm selected to do the refurbishment of the high-rise had never clad a high-rise building before. The lead architect did not familiarize himself with fire safety regulations for buildings.

The firm never checked if the materials they specified were actually suitable. Tower residents raised concerns about fire safety issues, but were not carefully listened to.

Cost-Cutting Compromising Safety

The lowest bid for construction was over 800,000 pounds over the budget. The landlord pushed the contractor to trim expenses.

To save money, the contractor proposed cost cuts, including replacing inflammable metal cladding, which the architects had preferred, with a cheaper alternative.

Failure of Local Government

The planning department of the local council, deciding only on the basis of its superficial appearance, chose Arconic’s folded panels—the ones that had catastrophically failed fire safety tests.

The council signed off on the refurbishment.

Fire Department Shortcomings

Firefighters arrived at the tower about five minutes after the first emergency call. They watched as the fire spread out a window and raced up the outer walls of the tower, using the flammable cladding as fuel.

In 18 minutes, the fire engulfed 19 floors.

The London Fire Brigade (LFB) knew of the risk of fire on the outside of high-rise buildings, but firefighters hadn’t been trained on it.

“We didn’t train people adequately,” the head of the LFB said.

The fire department advised residents to stay put in their flats until help arrived, rather than evacuate. They did this under the assumption that a fire will be contained in an apartment for at least an hour—not racing over 19 floors in just 18 minutes.

For Denis Murphy—and so many of his neighbors—this proved to be a fatal mistake.

Management Company Failings

Apartment doors in the tower were equipped with automatic door-closing mechanisms. This helps keep smoke inside an apartment, if there’s a fire and the apartment resident opens the door to flee.

But workers had removed some door-closers during repair work. The tower’s owners and the management company knew about this issue. A plan to regularly check door-closers was rejected.

The management company, the report stated, considered residents who raised safety concerns to be “militant trouble-makers.”

The report further stated the management company was seen by residents as an “uncaring and bullying overlord that belittled and marginalized them, regarded them as a nuisance, or worse, and failed to take their concerns seriously.”

In many fires, it is smoke, not flames, that causes fatalities. And at Grenfell, all those whose bodies were destroyed by fire died or became unconscious from toxic fumes, before flames arrived.

The Current Status

The Inquiry Panel released its damning and searing report. But what now?

The Panel made a series of safety recommendations. But the Inquiry Panel has no authority to see they are carried out.

And the UK government has no obligation to do anything with the recommendations.

And there is no formal process to communicate which recommendations the government accepts or rejects, or why they do so.

Although the fire was in 2017, there have been no prosecutions. The Metropolitan Police said its investigation will take 12 to 18 months before any charges are brought.

More than 3,000 buildings across England still have unsafe cladding.

A Systems-Informed Analysis

The Inquiry Panel asked, “How was it possible in 21st-century London for a reinforced concrete building, itself structurally impervious to fire, to be turned into a death trap?”

They responded to their own question: “There is no simple answer.”

The inquiry found that virtually every organization and entity involved in refurbishing Grenfell Tower was at fault to some degree.

The whole complex system of government regulators, suppliers, designers, builders, and building managers, the report found, needs reform.

The Value of Appropriate Regulation

The Grenfell tower inquiry shone a light on the “reckless deregulation” that contributed to the fire.

The report said that suppliers “engaged in deliberate and sustained strategies to manipulate the testing processes, misrepresent test data, and mislead the market,” and that a key regulatory body “was complicit in that strategy.”

The report called out the Department for Communities and Local Government, noting “The government’s deregulatory agenda…dominated the department’s thinking to such an extent that even matters affecting the safety of life were ignored, delayed or disregarded.”

The government-appointed United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UKAS), the National Accreditation Body for the United Kingdom, assesses organizations that provide certification, testing and inspection. Its vision involves building a “safe, secure” society.

The report found that UKAS “did not always follow its own policies,” and that “its assessment processes were lacking in rigor and comprehensiveness.” Even when failings were identified, “they were not properly explored and opportunities to improve were not always taken,” the report said.

Culture starts at the top. It’s the people with the most power—in the UK, the Prime Minister and their team—who set the tone for what is prioritized, and what is pushed aside.

A BBC reporter who followed the inquiry process over the years said that for her, the incident reveals a series of “unspoken truths about the British system.”

How safety was regarded as, at best, “not as a vote-winner; and at worst as an obstruction to the economy.”

And how regulation was viewed as “guidance to be bent.”

The opulent high-rises of London’s wealthy have excellent fire safety. But the homes of those who can only afford public housing? Many are sheathed in highly flammable coverings.

Regulation alone cannot fix the persistent social inequality in the UK, or anywhere else—particularly when government leaders collude with corporations to weaken, avoid or ignore regulatory requirements.

And even good regulations, when unfairly applied—for example by authoritarian governments—can have negative effects.

But although regulation isn’t the sole answer, good regulation is part of the solution.

Safety, Regulation, and Outdoor Adventure

In 1993, the drowning of four students on a kayak trip in England led to the world’s first national-level adventure safety legislation, the UK’s Activity Centres (Young Persons’ Safety) Act 1995.

But since then, the UK’s Conservative anti-regulatory government has mounted an effort to repeal the adventure safety law.

More recently, a multiple drowning incident on a paddleboarding trip in Wales showed remaining gaps in the UK’s regulatory system for risk management of outdoor adventurous activities.

It’s important to address all elements of the complex system—from government to industry and beyond—that is the led outdoor activities sector, in order to improve safety outcomes.

This was recently made clear in a recent zipline incident in Singapore, and in a death of a child at a school camp in South Africa.

No one step, no single culture change, no one regulation can improve adventure safety, or building safety.

No measure will enable Denis Murphy’s two brothers, and his sister, to hear his voice, his laugh, once more.

But a comprehensive, systems-informed approach, grounded in appropriate safety law and regulation, can help prevent future tragedies—involving everything from paddling and climbing to safe housing—from occurring.

The lessons from the Grenfell Tower tragedy aren’t new. And we shouldn’t have needed to learn them once again.

But outdoor and adventure professionals can take these bitter lessons and find ways to improve the safety of the services we provide to others.

Denis Murphy—a man who loved adventure and sport—would surely approve.