Alison Tilsley had a great sense of humor, and a love for everyone around her. She had a sunny nature, loved humorous wordplay, and would make jokes and puns. She was known by her family as a kind, caring and loving daughter, sister and auntie.

Alison, who went by Ali, also had a medical condition, hydrocephalus, where fluid builds up in the brain and can cause brain damage. As a result of her condition, she had limited motor skills, and so got around in a motorized wheelchair at Burdon Grange, the care home for persons with disabilities where she lived in Devon, in southwestern England.

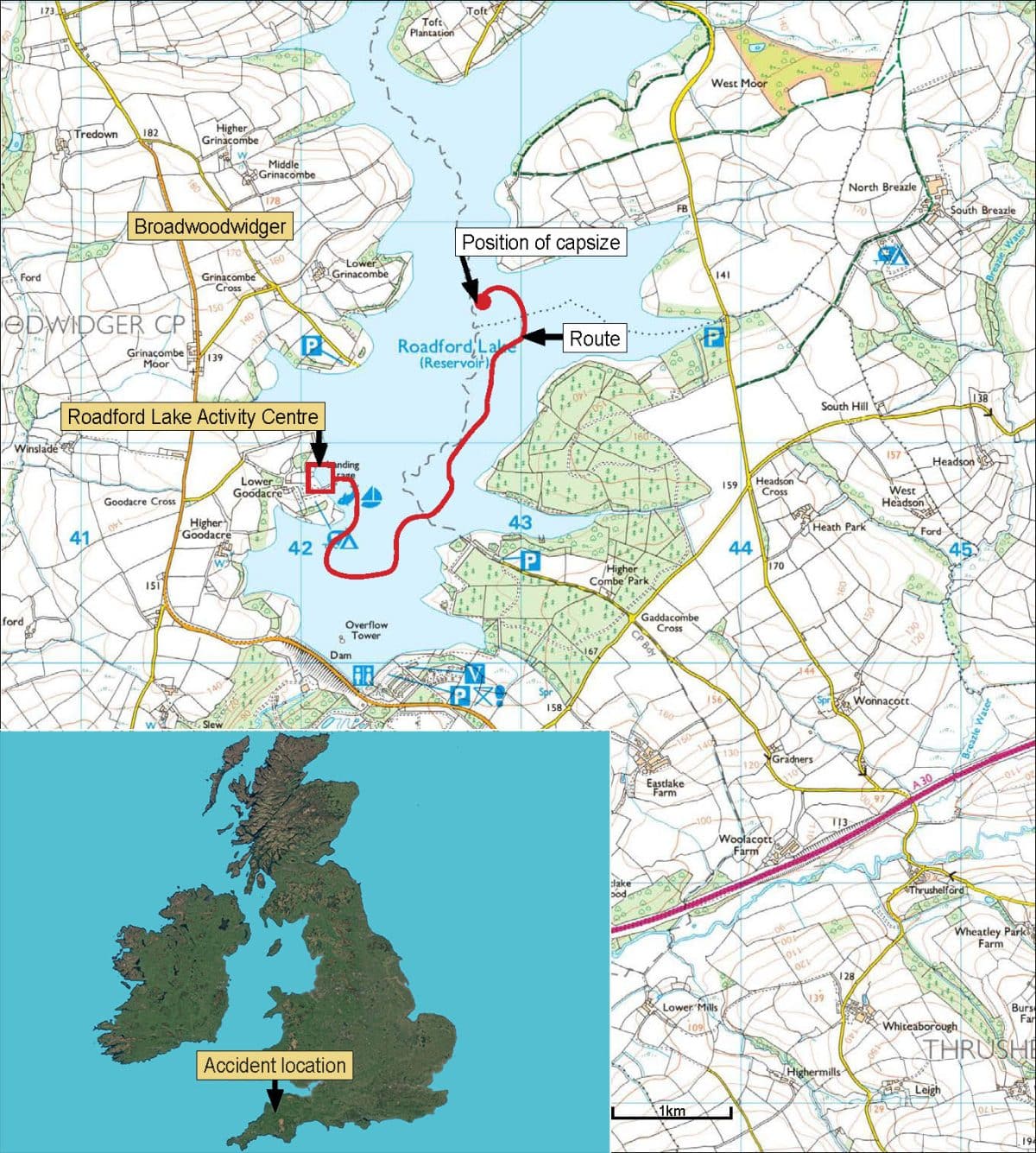

On June 8, 2022, the staff of the care home took her and other residents to nearby Roadford Lake, to take a scenic pleasure ride around the lake on a boat specially outfitted to accommodate wheelchairs.

The front part of the boat folded down to create a ramp, which allowed wheelchairs to roll on and off the boat. After the bow ramp of the boat was lowered, she and her fellow resident, Alex Wood, who had limited motor skills following a head injury, wheeled aboard on their motorized wheelchairs, each of which weighed more than 100 kg. It was a partly sunny day, with good visibility, and a fresh breeze from the southwest.

The boat began cruising down the lake, with Ali and Alex securely strapped to their wheelchairs. As the boat made a turn, it capsized, throwing all passengers into the water. Ali and Alex, strapped to their heavy wheelchairs, were dragged underwater and drowned.

Immediate Causes

An investigation determined that the boat capsized due to a loss of stability caused by an accumulation of water on the boat deck.

The water entered the boat because the once-watertight seal of the bow (front) door had degraded, allowing water to enter, and this was not noticed and fixed by the activity provider.

In addition, front-heavy loading of the boat caused the bow of the boat to be angled into the water (bow-down trim).

As water accumulated in the left front (port forward) corner of the boat, the bow down trim increased.

As the boat turned to the left, water flooded over the left front area of the boat.

The driver, whose view of the front of the boat was obstructed by passengers, stood up to see what was going on, and this added to the boat’s lean (heel) to the left.

The heavy motorized wheelchairs slid to the left, and the boat capsized.

Summary of Contributing Factors

In the investigation that followed the incident, inspectors found “a catalogue of failings.”

The Chief Inspector of Marine Accidents said, “No-one had taken time to properly consider the risks.” He continued, “In short, no-one had their eye on the risk, and tragically Alison Tilsley and Alex Wood lost their lives.”

As is often the case with serious incidents, shortcomings that contributed to the incident occurred at multiple levels of the complex system that is the outdoor sector. These contributing factors included:

- Inadequate management of activities. The activity provider’s operating procedures and managerial oversight were lacking.

- Inadequate staff training. Staff were not provided with sufficient safety information.

- Inadequate equipment management. A poorly-maintained boat directly led to flooding and capsize.

- Inadequate contractor management. The care center and the activity provider did not effectively cooperate to cover overlapping safety duties.

- Inadequate government oversight. The activity fell into an adventure safety law loophole, and local regulations were absent.

- Inadequate outdoor industry oversight. The accrediting body and the boat owner did not address safety lapses.

- Inadequate incident management. The activity provider’s planning for emergencies was insufficient.

- Inadequate Risk Management Committee. The activity provider’s health and safety committee was ineffective.

- Inadequate medical screening. The activity provider failed to adequately assess and respond to participant medical conditions.

- Inadequate Risk Management Reviews. Efforts at external safety audits were ineffective.

- Inadequate documentation. Important safety documents, like the boat owner’s manual, were missing.

- Inadequate accreditation. The boat fell outside the UK’s motorboating accreditation scheme.

- Inadequate systems-informed safety thinking. The activity provider relied on basic risk assessments rather than an effective, multi-layered, resilient safety system.

The investigative report, conducted by the UK government’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB), found that due to numerous inadequacies, “unsafe operation of the boat had continued unchecked.”

The Wheelyboat Ride

Preparation

Burdon Grange is a care home, which provides accommodation and care to persons with complex physical and nursing needs.

In May of 2022, the nursing home contacted Roadford Lake Activity Centre to arrange a half-day of boating on nearby Roadford Lake, near the village of Broadwoodwidger.

Roadford Lake Activity Centre is a subsidiary of South West Lakes Trust, which manages 40 lakes in southwestern England, and which operates five lake-adjacent Activity Centres focusing on water sports, fishing and camping.

Roadford Lake Activity Centre offers kayaking, canoeing, paddleboarding, sailing, fishing, a high ropes challenge course, archery, walking and cycling. Sports equipment is available for hire, and Centre staff also lead activities.

The Activity Centre also operated a boat designed and owned by The Wheelyboat Trust, which was built with a folding-down front which turned into a ramp, enabling wheelchair-users to easily enter and exit the boat.

The Wheelyboat Trust, a small organization of two staff plus a group of volunteers, fundraises to have the boats built by a local boatbuilder, and then provides the wheelchair-friendly vessels, known locally as a ‘wheelyboat,’ to various organizations to use with wheelchair-using passengers. The Wheelyboat Trust has used an unusual arrangement, where the Trust retains ownership of the boat, but the operator has possession of the craft, and manages its use and maintenance.

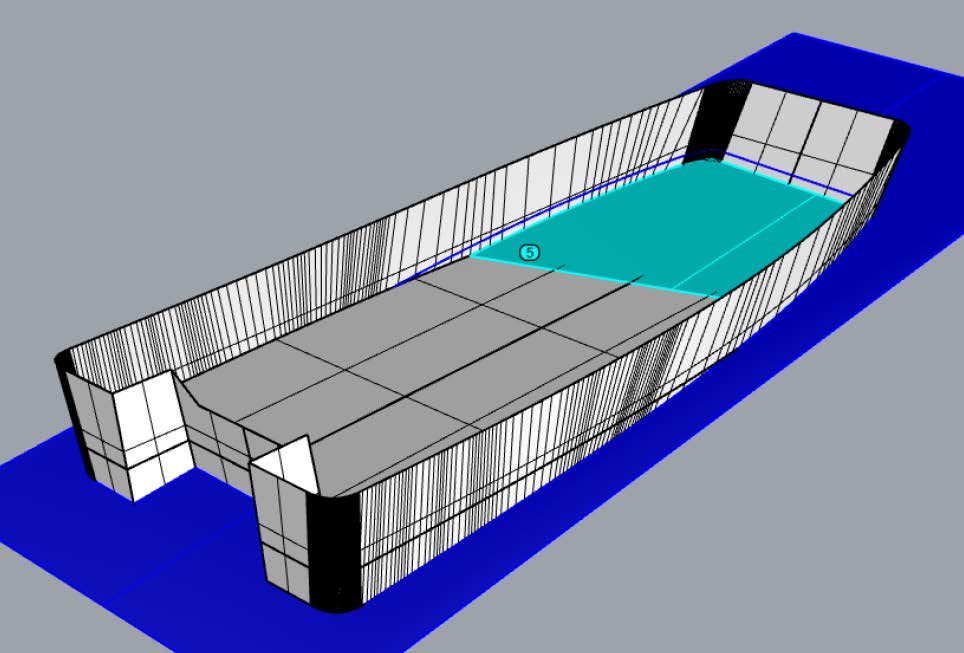

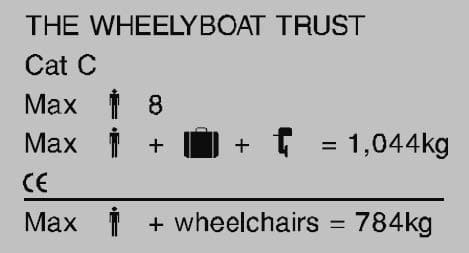

The Wheelyboat Trust provided Wheelyboat 123, a 5.3-meter long open aluminum-hulled motorboat, to Roadford Lake Activity Centre.

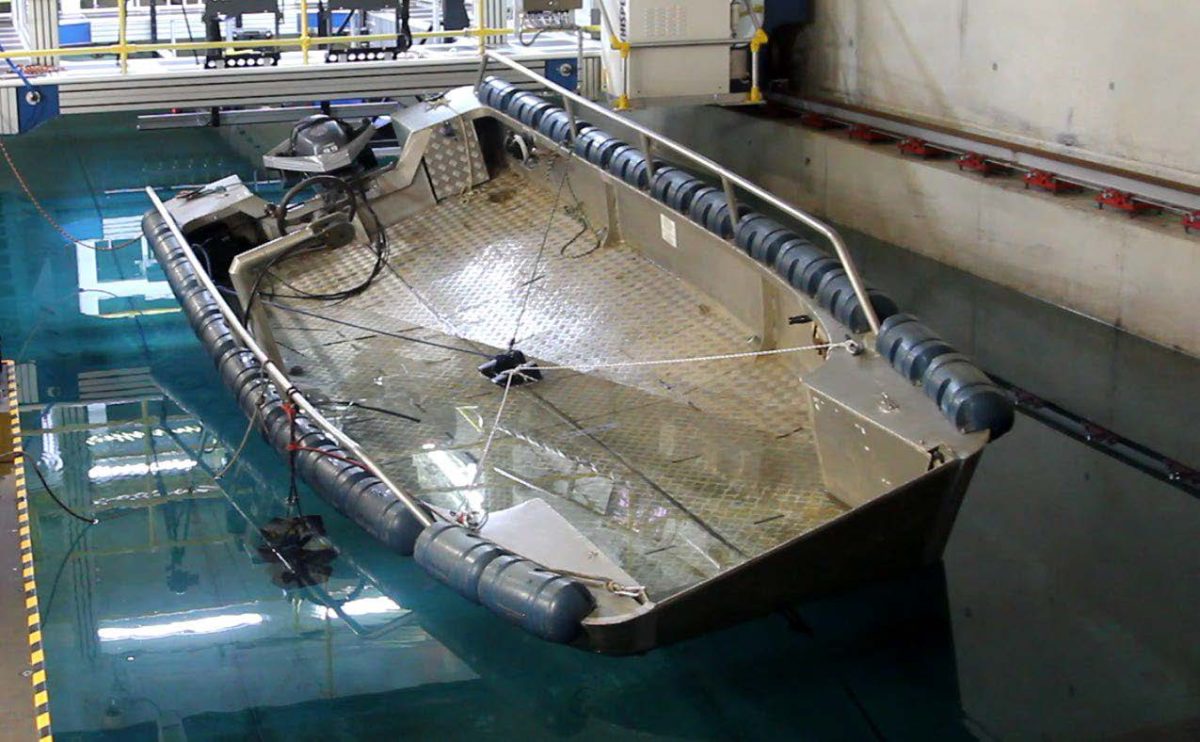

On the day the Burdon Grange care home residents were to arrive, an Activity Centre staff person was assigned to prepare the boat for their arrival. The staff person checked the engine and the operation of the bow ramp, and put a full can of fuel in the boat. They did not inspect the condition of the bow ramp seal.

Family members of the residents were not informed of the upcoming trip, and Burdon Grange did not seek consent for the boat trip from the residents’ families.

The First Trip

Six care home residents, three carers, and the care home’s transport manager arrived at the Activity Centre. They received buoyancy aids and a VHF radio. Centre staff checked that the transport manager knew how to operate the boat.

While others waited on shore, one group of three residents, a carer and the transport manager boarded the boat. The bow ramp was winched up into place. At this point the waterline of the loaded boat was just below the bottom part of the bow ramp, meaning all parts of the bow ramp were out of the water. The boat took a 40-minute tour of the lake, returning successfully to the launch site.

A small amount of water had accumulated on the boat deck; this was attributed to water spray coming over the side of the boat. An Activity Centre instructor swept out the water.

The Second Trip

The second group to board the boat was larger: two carers, the transport manager, two residents (Ali and Alex) in motorized wheelchairs, and a third resident in a manual wheelchair.

The motorized wheelchairs were positioned in the centerline of the boat, towards the bow, with the third wheelchair behind them on the port (left) side. All passengers were wearing buoyancy aids, and the brakes were set on the wheelchairs.

The driver headed the boat away from shore. At this point the waterline of the loaded boat was above the bottom part of the bow ramp, meaning that the lowest section of the bow ramp was submerged under water.

A carer noticed that water was leaking into the boat around the edges of the bow ramp. The bow ramp was winched more tightly closed, but the water now on the deck was not removed.

The boat resumed heading out onto the lake.

As the boat cruised north up the lake, sprays of water splashed into the boat. Water about 2 cm deep, with total weight of about 145 kg, accumulated towards the front of the boat.

The boat reached the turnaround point, and began to turn to port (left) to head back to the Activity Centre. More spray was splashing into the boat.

As the boat turned, a carer saw a large quantity of water coming over the port forward (left front) corner of the boat, and alerted the boat driver. The boat began to heel to port (tilt to the left side). The bow was angled downwards into the water.

The driver, whose view of the front of the boat was blocked by passengers, stood up to see what was going on.

The motorized wheelchairs began to slide to the left. The boat capsized.

Ali’s and Alex’s medical conditions severely limited their ability to extricate themselves in case of an emergency. The weight of the motorized wheelchairs to which they were strapped dragged them, in the words of the report, “to the bottom of the lake.”

The resident who had been in the manual wheelchair was found submerged underneath the overturned boat, and was brought into a rescue boat, where CPR began. That resident, who had not been breathing, began to breathe again. They and the care center staff were rescued and brought ashore.

Efforts throughout the day and evening to locate Ali and Alex were not successful.

The following day, police divers recovered their bodies.

Analysis

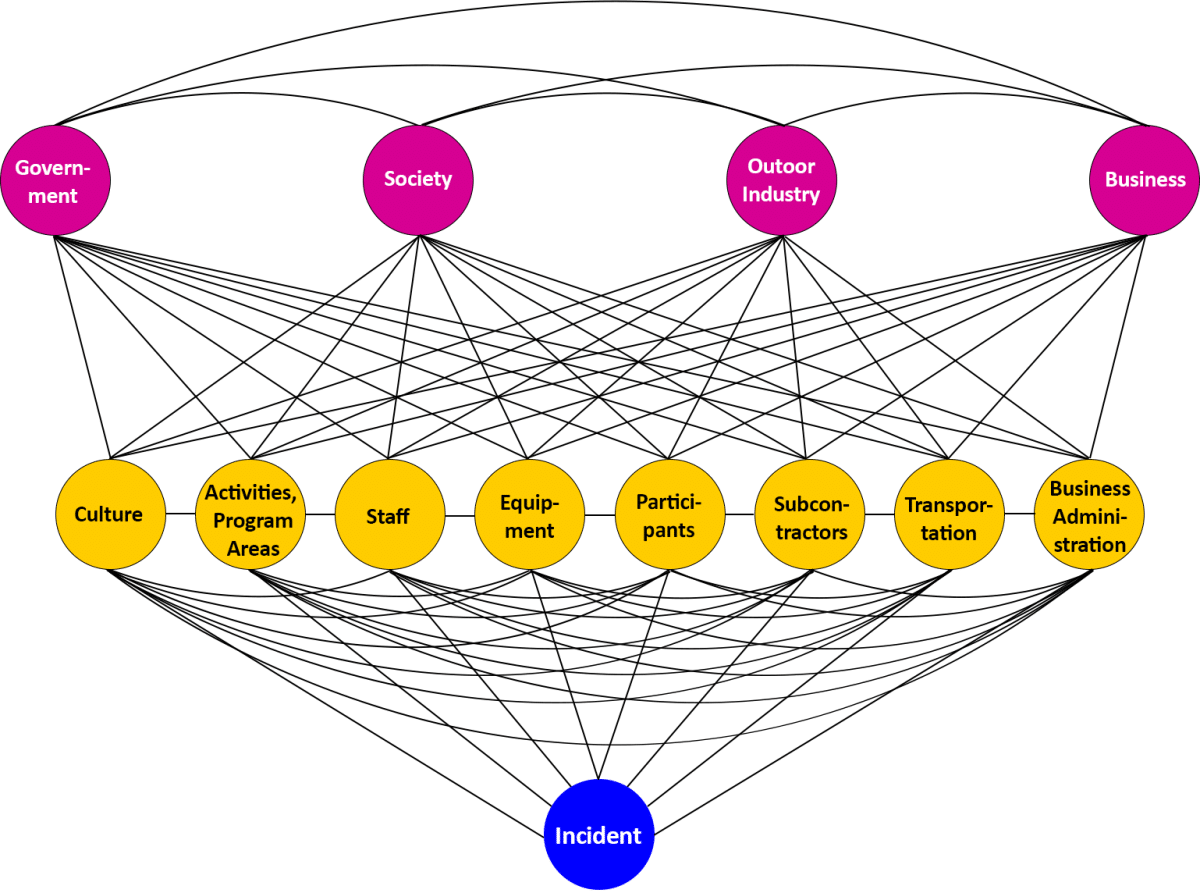

The MAIB report identified a number of factors that led to the tragic incident. We can view contributing factors through a theoretical model of incident causation, such as the Risk Domains model.

In this model, risks that directly contribute to an incident reside in various direct risk ‘domains,’ or reservoirs, such as staff and equipment.

Issues in underlying risk domains, such as the role of the outdoor industry and government, contribute indirectly to the occurrence of an incident.

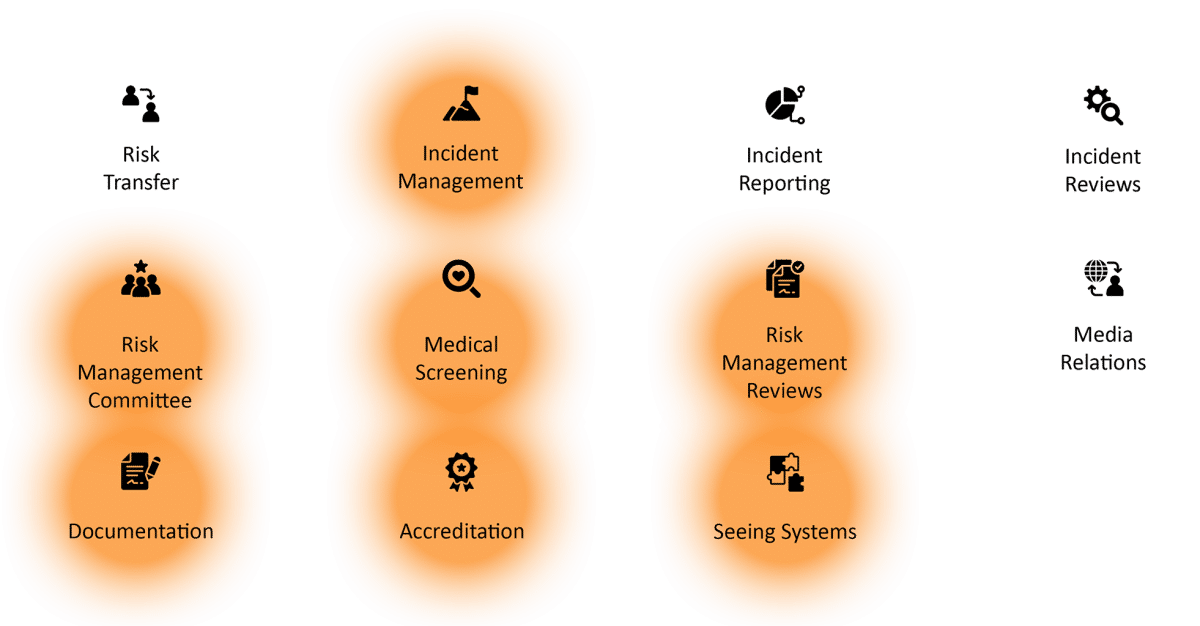

Also in the Risk Domains model, various “Risk Management Instruments,” or broad-based tools, such as formal risk management reviews (safety audits), accreditation, and a Risk Management Committee, can help prevent an incident.

Using this model, we can organize opportunities for safety improvement illuminated by the MAIB report. The model can be used to create a visual aid to help organizations plan for preventing future incidents.

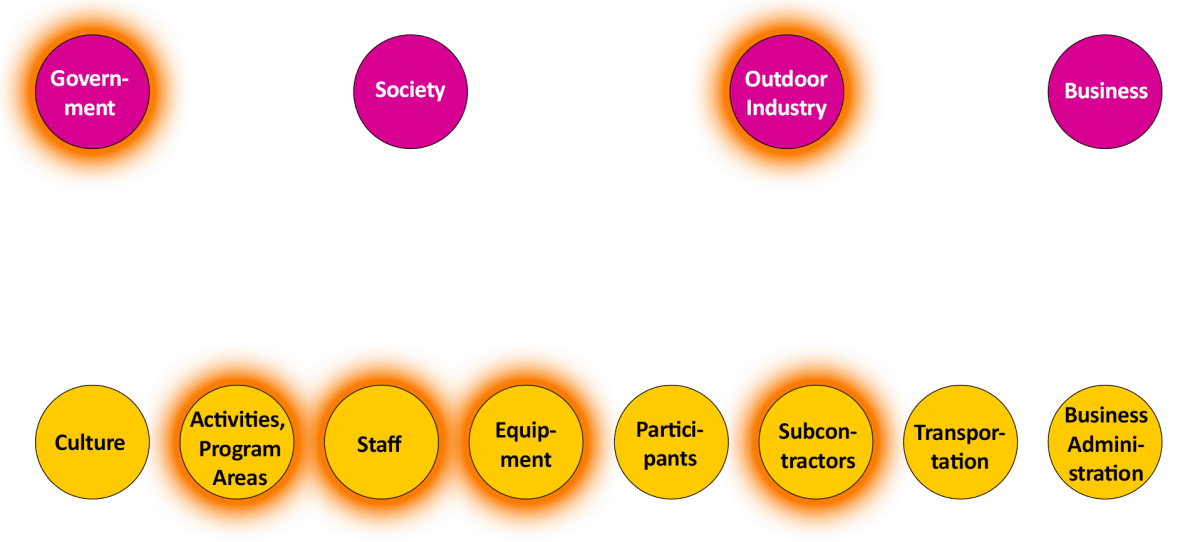

The incident investigation illuminated six risk domains where additional investment could improve future safety outcomes:

- Activities and Program Areas

- Staff

- Equipment

- Subcontractors

- Government

- Outdoor Industry

These are indicated in orange, below.

Seven risk management instruments where opportunities for improvement exist were also brought to attention.

- Incident Management

- Risk Management Committee

- Medical Screening

- Risk Management Reviews

- Documentation

- Accreditation

- Seeing Systems

These are highlighted below.

We’ll address these 13 items one by one.

1. Activities and Program Areas

The “Activities and Program Areas” risk domain refers to understanding the risks associated with outdoor activities, and the areas in which they occur, and suitably instituting policies, procedures, values and systems to adequately manage those risks.

Risk management by administrators

It is the responsibility of the activity provider’s management to identify risks specific to the organization’s activities and program areas, and put in place the operational infrastructure to address them.

The parent organization of Roadford Lake Activity Centre, South West Lakes Trust (SWLT), is a £5 million charitable organization with over 140 employees. The Trust had a CEO, a senior leadership team, a nine-person Board of Trustees, several Visitor Experience Managers, and Chief Instructors and Activity Instructors.

The organization had a health and safety policy, an independent auditor who assessed the organization’s regulatory compliance, and a regular health and safety committee with meetings attended by the CEO, senior leadership team, managers and a trustee representative.

Managers were responsible for identifying areas where risk assessment and formal documentation, including safety procedures, were required.

Each of the organization’s five Activity Centres open to the public was issued an activity centre procedures document by SWLT. The document came with a set of task-specific and site-specific risk assessments. Printed and electronic copies of risk assessments and procedures documentation were kept.

Risk assessments pertaining to all Activity Centres were generated centrally at SWLT, and each Activity Centre could create specific risk assessments for their particular conditions.

Board of Trustee meetings reviewed health and safety, as did SWLT’s every-two-week leadership team meetings. The results of safety audits were a regular agenda item. (No issues with the operation of the Roadford Lake Activity Centre management system were reported.)

Roadford Lake Activity Centre had a procedures document describing safety responsibilities, hazards, health and safety policy, safeguarding policy, and code of conduct. It also described SWLT’s emergency action plan, training requirements, and a code of conduct specific to safety boat operations.

The document included operating procedures for each activity held at the Centre, and general operating procedures including accident reporting and safety briefings. The document was reviewed annually, and was last updated in February 2022, four months before the incident.

The document contained a watercraft safety briefing that instructors were to deliver before use of any watercraft on Roadford Lake. No specific instructions or safety briefing items for the use of Wheelyboat 123 were included in the document, but the briefing covered nine topics:

- Explain and show the areas covered by the Safety Boat Cover.

- Explain the ‘No Go’ areas, e.g. Dam, Nature Reserve, Cable ski area’s.

- Explain areas for caution e.g. weeds, shallow, rocky or muddy areas.

- Warn water users to keep 30 metres from Anglers.

- Respect other water uses.

- Show distress signal if they need assistance, e.g. raised arms.

- Show and explain the flag system and horn which is used if general recall is needed.

- Check all participants are wearing buoyancy aids and other safety equipment as appropriate.

- Monitor on water progress. [sic]

On paper, this looks like an impressive, thorough and likely effective safety management system. There are documents, procedures, committee meetings, discussions, safety audits, layers of oversight, and systems for creating and evaluating safety measures.

And yet, in the incident and the investigation that followed, it became clear that this was not adequate to suitably identify and manage risks related to the organization’s activities and program areas.

Investigators said:

“It is concerning that the internal governance and oversight systems in place were insufficiently robust to ensure the continued safe operation of Wheelyboat 123.”

The MAIB report noted the additional vulnerabilities wheelchair users face when on the water. The report stated, however:

“The senior management team at SWLT did not recognise this, and instead placed reliance on the activity centre’s instructors to manage the use of the boat. The lack of oversight by SWLT allowed vulnerable users to be put at additional risk of injury or death.”

Boat operating SOPs

Let’s look more closely at the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the wheelyboat.

The procedures document for the wheelyboat covered a variety of safety-related items, including a requirement to check the boat.

But it did not specify what should be checked or how the check should be conducted. It did not include a check of the bow door seals.

The procedure did not mention how wheelchairs should be managed on deck, for example to avoid dangerous conditions like bow down trim.

The procedure required the driver to “show competence,” and referenced an assessment document. But neither the procedure nor the assessment document described how passengers were to be loaded. And there was no reference to stability, or to the hazard of water on deck.

The training Burdon Grange’s driver received had no discussion about longitudinal trim—that is, avoiding a bow-down trim.

An SOP document that met technical writing standards for precise, specific procedures, which included more detail on how to manage wheelchairs and the unique risks of wheelyboats, might have helped lead to a different outcome.

OEM instructions & SOPs

When using technical equipment in outdoor or adventure activities, it’s generally a good idea to follow the recommendations of the original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

An earlier version of the wheelyboat was designed so that the bottom of the bow ramp was above water, when the boat had a bow up trim, even when the maximum number of crew were aboard.

In 2009, The Wheelyboat Trust sought to make changes to the boat’s design. With the new version, the bottom of the bow ramp was just below the waterline when at the maximum stated crew limit.

This meant that ensuring the bow ramp seals were intact was important, so that water would not accumulate on the deck.

The updated boat owner’s manual said, under a header “Risk of loss of stability:”

The boat should never carry more than the manufacturers recommended load. The load should be suitably distributed, bearing in mind that stability is most significantly reduced by any weight high up in the boat, or towards either side.

Best practice is to load the boat with a level trim port and starboard and a bow-up trim fore and aft – this will help prevent water being pushed above the bow door threshold at slower speeds.

Avoid a bow-down trim with any load. [sic]

The manual also noted that free water on the deck significantly reduced the wheelyboat’s stability and should be removed immediately.

These essential instructions were not included in SOPs, and in fact, the owner’s manual itself was misplaced, and not available to Activity Centre staff.

The report noted: “On the day of the accident, Wheelyboat 123 completed two trips, the first passing without incident and the second resulting in capsize. The difference between the two trips was the boat’s loading.”

The second trip had more weight—more people, and more wheelchairs. And the heavy motorized wheelchairs were positioned farther forward in the boat.

These two factors led to the boat sitting lower in the water, and having a bow down trim (the front of the boat angled downward into the water), with the bottom of the bow door under the water.

The Activity Centre’s risk assessment did not mention loading considerations. Neither did its use instructions. And neither of the two copies of the owner’s manual that WBT had supplied to the Centre—which emphasized avoiding bow down trim—were anywhere to be found. This led the investigators to conclude that the instructors were likely unaware of the importance of trim, and to state:

“The loading of Wheelyboat 123 on the accident trip, and the position of the motorised wheelchairs, caused a bow down trim that allowed water to accumulate on deck. This happened because the activity centre instructors did not understand the importance of longitudinal weight distribution.”

2. Staff

The “Staff” Risk Domain considers areas including staff competence and training, and communications with staff. The report found the Activity Centre had shortcomings in these areas.

(“Staff” includes, in this case, both Activity Centre employees and the boat driver, an employee of the care center.)

Training on Wheelyboat-Specific Safety Procedures, for User Group

A core reason the boat capsized was that staff on the boat were not properly trained to understand and address risks specific to the boat.

Water leaked into the boat through the bow ramp seal, accumulating in the boat’s port forward (left front) deck area, compromising the boat’s stability.

Boat driver training provided by the Activity Centre focused on operating the engine and maneuvering on the water. It did not include any of the instructions or information contained in the owner’s manual, including the hazards of water on deck. It did not adequately address how to recognize the danger of bow down trim, or the critical need to keep water off the deck.

The report stated:

“The effect of the accumulated water on the boat’s stability was not understood by the occupants, and the driver could not see the bow area and did not have the competence to recognise the hazard.”

The carers were forward of the boat driver, and could potentially have seen dangerous water ingress and alerted the driver. But the carers were focused on attending to the residents, and were not trained to understand the hazard of water on the deck.

The training for boat drivers also did not cover boat handling characteristics, or maximum load and load distribution. No specific details were included about operating with wheelchair users aboard.

And the driver training contained little information about emergency procedures. The report noted:

“Without the necessary guidance or details of what to do in an emergency, the driver was not equipped to deal with the situation.”

Training on Wheelyboat Hazards, for Activity Centre Employees

If the Activity Centre’s instructors had been knowledgeable about the unique characteristics and hazards of wheelyboat operations, they could have passed that information on to rental groups such as Burdon Grange.

But investigators found safety training of new employees was of a general nature, and that instructor staff were not given specific training on the operation of Wheelyboat 123. The training did not address the hazards introduced by a bow ramp, the importance of longitudinal trim (avoiding lean to the left or right), or the necessary considerations when operating with wheelchair users on board.

The wheelyboat owner’s manual described the importance of keeping water from accumulating on the deck, and the importance of maintaining the watertight seal on the bow ramp. However, the Activity Centre’s copy of the owner’s manual could not be found, so this information was unavailable to instructors.

The builder’s plate and safety notices that had been present when the boat was placed at the Activity Centre were also missing, so the important safety information they held was also unavailable to instructors.

And no one at the Centre appeared to have appreciated the significance of this. Nor had the absence of these documents been identified as a defect during routine inspections.

Investigators concluded that the dangers of water leakage into the boat were not communicated to the driver or occupants of the boat, because the instructors did not understand the risk.

The investigators stated:

“It was likely that the activity centre instructors were unable to deliver an appropriate level of wheelyboat-specific training because they lacked the required knowledge to do so.”

Training on Procedures Regarding Wheelchair Users

The wheelchair-accessible motorboat was provided to Roadford Lake Activity Centre for the primary purpose of providing boat excursions to wheelchair users. However, there was little reference to this in the Centre’s documentation.

Disability awareness training covering all aspects of interacting with disabled people was widely available by training bodies in the region. These training are designed to help individuals provide effective services for disabled people, and to understand the risks and barriers involved with providing activities to persons with disabilities.

However, disability awareness training was not required for any Activity Centre staff. There were no records showing staff had received any training in working with people with disabilities.

The report concluded:

“There was insufficient understanding of the challenges faced by either the wheelchair users or their carers, when undertaking activities on or near the water, and the risk assessment did not identify hazards associated with having wheelchair users on the boat.”

Other factors

The report also raised other staff-related issues that may have contributed to the incident. These included:

- The Activity Centre’s instructors were largely seasonal, so important information and learning could have been lost.

- There was no single staff person who was responsible for the upkeep and operations of the boat.

- The wheelchair-accessible boat was somewhat outside the Activity Centre’s core activities, which could have led to instructors and boat users not being fully aware of essential safety factors.

3. Equipment

The “Equipment” Risk Domain is concerned with how equipment is selected and managed. Problems with personal flotation devices and the boat involved in the incident were identified.

PFDs

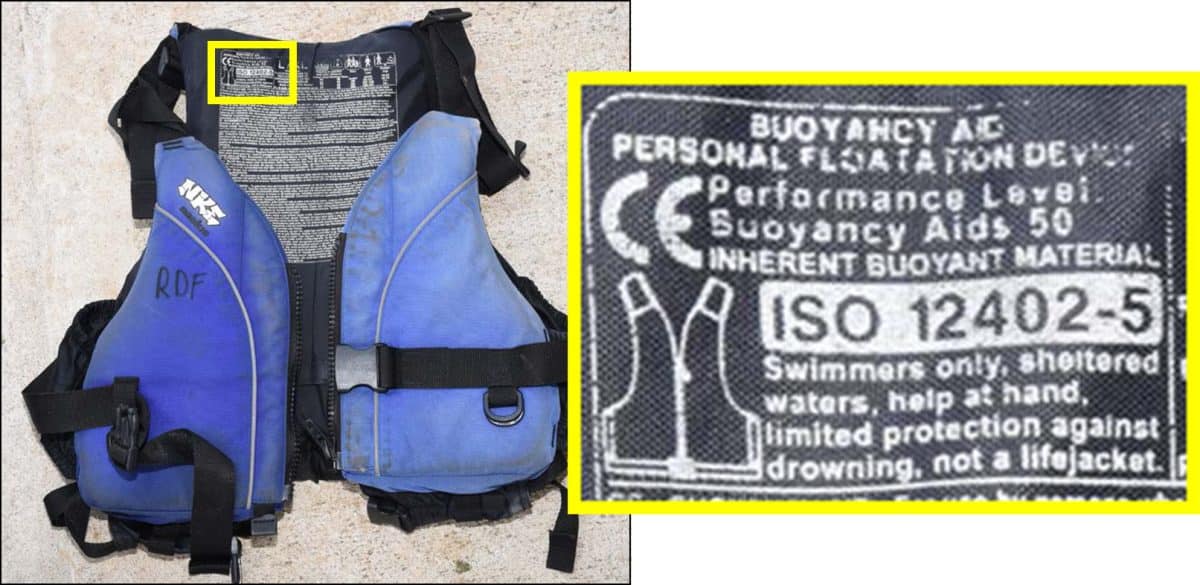

Personal floatation devices (PFDs), as commonly used in the UK, come in two different types: buoyancy aids and life jackets.

Buoyancy aids simply help a person float, or stay buoyant. Their use is suitable when the wearer is able to help themselves to some degree by swimming to safety, or if they just need to keep floating above water until help arrives. They are designed to be used when help is close at hand. Buoyancy aids are designed for swimmers, and are unsuitable for non-swimmers, people who cannot keep their face clear of the water, and those who cannot assist in their own recovery.

Life jackets offer additional protection. Life jackets are designed to turn an unconscious person who is face-down in the water to a safe position. No subsequent action is required by the user to maintain this position. Life jackets have 150 newtons (N) of buoyancy and a full collar to support the head and neck.

The wheelyboat owner’s manual stated that lifejackets, as opposed to buoyancy aids, should be worn at all times by everyone on board. They should be to a minimum of 100N on sheltered waters and 150N on exposed waters.

The procedures document for wheelyboat use (shown earlier in the “Activities and Program Areas” section) stated, “All occupants to wear life jackets [sic].”

However, the boat passengers were issued buoyancy aids, with a nominal rating of 50N. No lifejackets were available to water users at the Activity Centre.

The label inside the buoyancy aids said: “Swimmers only, sheltered water, help at hand, limited protection against drowning, not a lifejacket [sic].”

Investigators stated:

“In the context of people with limited capability to assist themselves in an emergency, and who were dependent on the assistance of carers, buoyancy aids were unsuitable and unsafe.”

The Activity Centre used to have 150N lifejackets, in 2018. It was unknown at what point lifejacket use was discontinued, and buoyancy aids were put in their place.

Even a fully-featured 150N lifejacket would not be expected to keep a person strapped to a 100kg wheelchair afloat.

However, systematically using buoyancy aids with disabled persons, including when the documentation directed otherwise, led investigators to conclude:

“Centre staff did not question the suitability of buoyancy aids for people who could not swim or had no confidence on the water…the issuing of buoyancy aids to the users of Wheelyboat 123 indicates that the activity centre had given little consideration to a disabled person entering the water, or the flotation required to keep that person afloat.”

Boat inspection

When the boat arrived at the Activity Centre, a monthly inspection itinerary was established. It was based on existing powerboats at the Centre, however, and did not include specific requirements in the wheelyboat’s owner’s manual.

The monthly maintenance and inspection routine was generic to all powerboats used at the Centre. It did not include checking the condition of bow ramp seals—even though this has been included in the organization’s wheelyboat risk assessment. The routine also did not include inspection of buoyancy tanks for integrity.

After a damaged buoyancy tank caused a wheelyboat near Bristol, England to capsize in 2016, WBT emailed the Roadford Lake Activity Centre with instruction to inspect the buoyancy tanks monthly. However, the maintenance routine was not updated to reflect this.

Boat maintenance

Inadequately detailed maintenance system.

The Activity Centre’s planned maintenance system did not include maintenance tasks specified in the owner’s manual, such as regular inspection of the bow ramp seals.

The system merely instructed staff to check for the presence of various times.

Staff, therefore, did not understand the significance of maintaining all parts of the boat in good order.

As a consequence, bow seals degraded and water began to leak into buoyancy tanks, but these problems were not identified or rectified.

A leaking bow seal was identified in April 2017. However, the boat was used by multiple groups, including wheelchair users, for four months, before the issue was fixed. This put users at considerable risk, and illustrated that staff did not understand how to properly maintain the boat.

Inadequate buoyancy tank maintenance.

The boat’s buoyancy tanks help keep it afloat. However, inspection of the boat after the incident showed water had infiltrated one of the tanks. (How much of this occurred before the incident was unclear.)

Water in the buoyancy tank will add to the overall loading of the boat. And if the water settled in the forward end of the tank, it could have contributed to the bow down trim.

An inspection found small cracks in the deck, which could be how water ended up in the buoyancy tank.

WBT provided the Activity Centre with information in 2016, highlighting the importance of checking the buoyancy tanks.

Despite this, there were no maintenance records of the buoyancy tanks ever being inspected.

The report concluded that the accumulation of water in the buoyancy tank was “a further indication of poor maintenance and inspection practices at the activity centre.”

Incomplete recordkeeping.

Maintenance records for the boat were regularly missing records of monthly inspections. Records of action taken to remedy defects was not always recorded, nor was a record that repair work was completed.

A number of inspection reports simply stated “good.”

Inspection reports from August 2017 until the last inspection before the June 2022 incident did not comment on the condition of the bow door seal, or the buoyancy chambers.

Ineffective defect reporting.

Inspectors found “substandard maintenance and inadequate inspection over a period of time.” This issue was compounded, however, by a poor defect reporting system.

The Centre’s system for managing maintenance issues did not record actions taken after a defect was reported. Defects were not recorded as have been addressed, following completion of repair. Details of repairs were not documented.

This made it difficult for executives to understand whether equipment was appropriately managed and safe to use. Investigators found that the organization’s defect reporting system was ineffective at flagging up matters of concern. The investigators stated:

“A lack of defect reporting, and scant information after inspections, meant that records obscured the boat’s condition from senior management, who had overall responsibility for health and safety.”

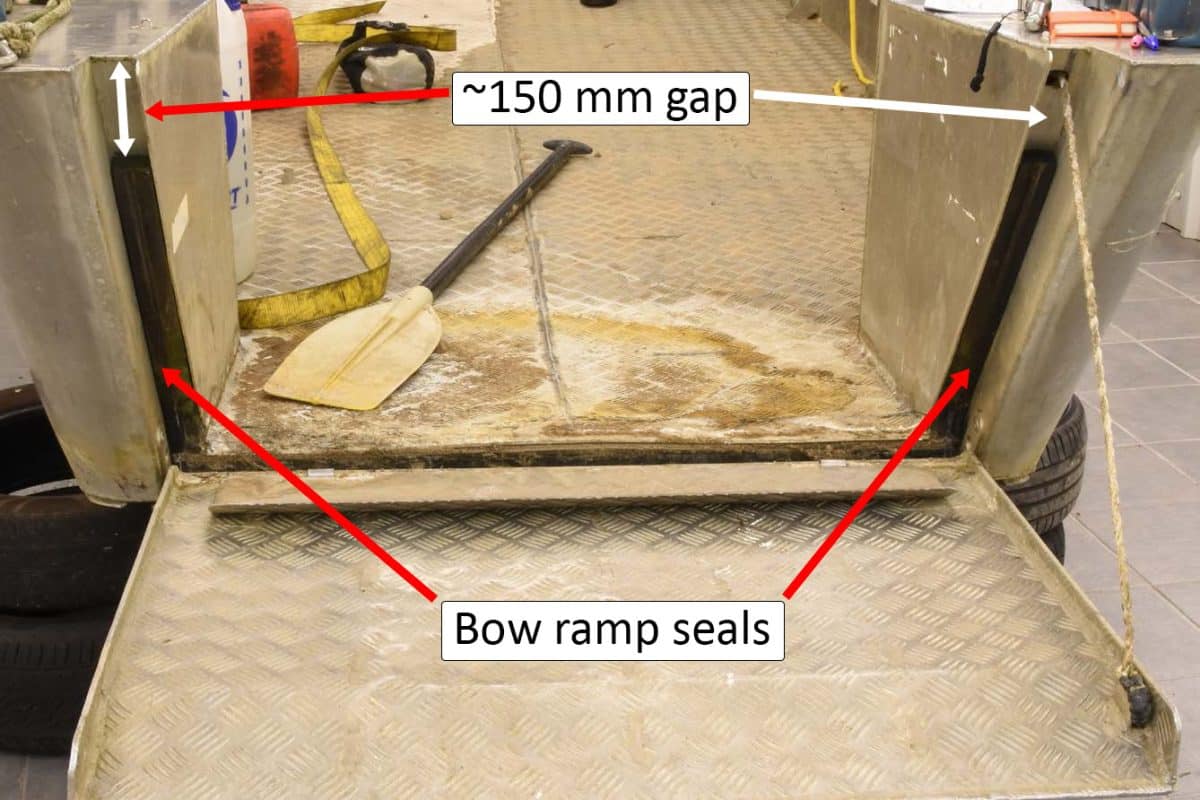

After the incident, the vessel was taken to police storage and inspected. Examination results included, among other findings:

- Safety notices and builder’s plate were missing from inside of bow ramp.

- Bow ramp vertical seals did not extend the full length of the bow ramp channel. A 150mm long section from the top of the channel was missing. (See image below.)

- The bow ramp watertight seal was degraded and deformed with debris embedded in the seal. This debris likely allowed ingress of water through the bow ramp.

- A chalk test on the bow ramp seal indicated that the seal was not effective along its entire length.

- The bow ramp seal failed a hose test, allowing water to pass the seal.

- Seventeen liters of water were drained from the starboard buoyancy tank.

- There were small cracks in the deck.

- On the bow ramp, the welded hinge plate had a circumferential crack. This allowed water to leak into the hollow bow ramp structure and onto the deck. The water-filled bow ramp also reduced boat stability and added to the bow-down trim.

- The secondary clip did not hold the bow door tight against the door seal.

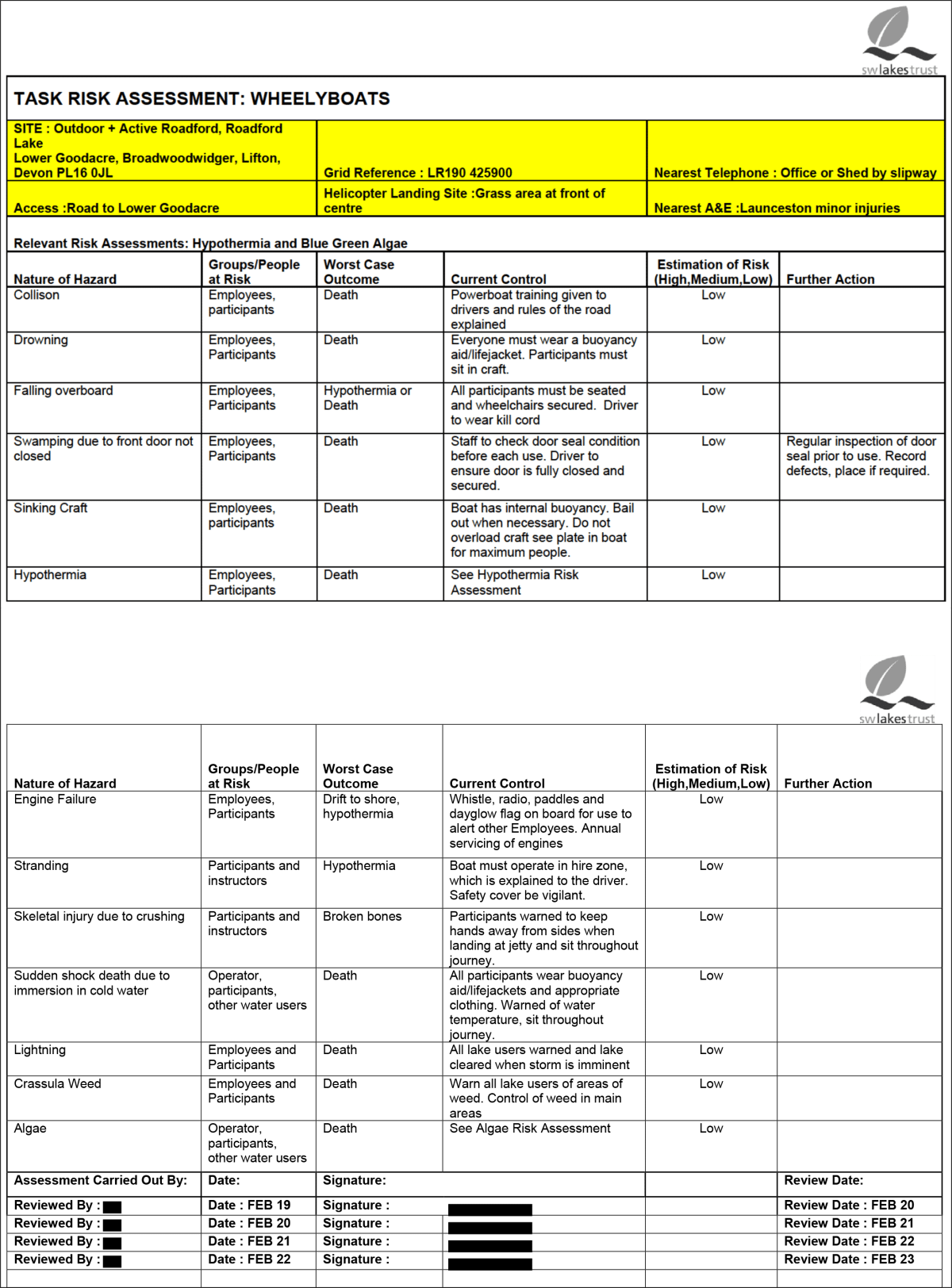

Wheelyboat Risk Assessment

Roadford Lake Activity Centre had a “task risk assessment” for wheelyboats. A principal purpose of probabilistic risk assessments (PRAs) is to identify reasonably foreseeable risks, and to document management measures used to reduce or eliminate those risks to an acceptable level.

In this case, risk management measures documented in the PRA were not fully connected to actual practice.

For example, the risk assessment listed a hazard “swamping due to front door not closed.” Management measures included:

- Staff to check the condition of the door seal before each use

- Driver to ensure door is fully closed

- Record defects

However, these management measures did not consistently or adequately occur.

As another example, “sinking craft” was listed as a hazard. Users were instructed to “see plate in boat for maximum people.”

However, the builder’s plate with maximum weight limits was missing. The wheelyboat procedures document only listed the maximum number of occupants, and did not contain weight limits.

This meant that instructors had no way of assuring the maximum load limit was not exceeded. Inspectors concluded that because of this, “there was a risk that the boat could be overloaded.”

In addition, the report pointed out that risks related to improper loading or loss of stability were not listed in the risk assessment.

Oversight measures that could have helped ensure the risk assessment document was fit for purpose and appropriately used fell short. The risk assessment had been reviewed each year by a designated staff person. The most recent review prior to the incident was February 2022.

These concerns point out some structural issues with the use of probabilistic risk assessments as a safety tool.

- Ineffective without links to procedures & accountability. If the risk management measures noted in a risk assessment are not operationally tied to detailed written policies and procedures, and also linked to suitable supervision and reporting systems, there is a likelihood that those risk management measures will not actually be taken.

- Oversimplified incident causation model. Risk assessments that treat each risk in isolation from the others may be suboptimally ineffective. Major incidents often occur because of combinations of risk factors. Linear-style PRAs fail to manage for this complexity by building a resilient, multi-layered system where the failure of one element does not lead to catastrophe.

- Hazard lists are inherently incomplete. It’s not possible to list every potential risk. However, by themselves, risk assessment spreadsheets don’t foster the development and use of broadly effective SOPs, policies and management systems that can scoop up and address unlisted risks.

- Control measure summaries are over-brief. For example: the risk assessment said “Everyone must wear a buoyancy aid/lifejacket.” This fails to distinguish between the two items, or to describe under what conditions each is suitable. “Do not overload craft” verges on the meaningless, if personnel do not know what the load limits are, and have guidance on how to measure against them. Clearing the lake when a lightning “storm is imminent” is too open to interpretation unless “imminent” is further defined.

A risk management model that does not rely on a probabilistic risk assessment as a primary tool for ensuring safety, but uses detailed SOPs—along with training and accountability measures to ensure they are appropriately communicated and used—may be a more effective model of activity-level, in-the-field risk management for outdoor, travel, experiential and adventure programs.

Boat design

Serious questions were raised about the boat’s design.

The University of Southampton’s Wolfson Unit for Marine Technology and Industrial Aerodynamics (Wolfson Unit) conducted a stability assessment of the boat, in a towing tank on the university’s campus.

The boat was assessed against the ISO 12217-3 standard in design category C, an inshore design rating for boats operating in coastal waters, large bays and lakes with winds to force 6 and a significant wave height up to and including 2 m.

The boat failed the load assessment, and was found to not comply with the ISO design category C stability and buoyancy requirement. The assessment indicated that when the heeling moment corresponding to a crew limit of eight people was applied, the stability model predicted that the vessel would heel to one side until the cockpit became swamped.

This, however, is not considered to be a significant contributing factor in the incident; the predominant immediate causal factor was the accumulated water in the bow area.

The university also conducted a computational fluid dynamics study. In this study the university noted that vessels fitted with bow ramps typically exhibit a pronounced bow wave, whose size is speed-dependent. The study concluded that the boat likely had a significant bow wave, which at a speed of six knots would exceed the height of the seal of the port ramp edge, “which would result in progressive flooding of the cockpit.”

The flooding of the cockpit led to an accumulation of water on the deck, which reduced the boat’s stability. The university concluded that “the capsize would not have occurred without the accumulated water on deck.”

4. Subcontractors

Risk management becomes more complex when there are multiple organizations involved in the planning and delivery of an outdoor or adventure program.

In this case, there were three organizations involved:

- The Wheelyboat Trust, which owned the boat

- Burdon Grange, which supplied the boat driver, and which had deep knowledge of the abilities and medical condition of participants

- Roadford Lake Activity Centre (and its parent company, South West Lakes Trust), which managed the lake and rented out the boat

Each of these organizations has a duty with respect to safety. But not only that, each organization has a responsibility to “consult, cooperate and coordinate” activities with the other organizations with whom they share overlapping safety duties.

The Wheelyboat Trust knew the regulatory requirements and good practice standards regarding wheelyboat use.

Burdon Grange knew the needs and abilities of its residents, for example their ability to assist themselves in case of falling overboard.

The Activity Centre knew the details of the outdoor recreation activity (a trip around the lake) and the activity area (the lake), such as boat driver training and site-specific emergency procedures.

Effective communication between the three entities is essential for good safety management.

The report found shortcomings in the organizations’ actions, individually and as a group, including:

- Activity Centre instructors did not discuss residents’ capabilities with care home staff.

- The Activity Centre lacked understanding of the needs of wheelchair users.

- The Wheelyboat Trust did not take steps to ensure boat recipients met WBT’s safety requirements, for example by ensuring recipients submitted required condition notes, or following up when their safety survey was not returned.

- Burdon Grange had no specific risk assessment for water-based excursions, and did not question the instructor regarding suitability of the boat trip for residents who needed to be strapped into wheelchairs.

- Burdon Grange staff lacked the competence to risk-assess water-based activities.

Investigators found that neither Burdon Grange nor the Activity Centre had properly considered the risks associated with taking residents on the boat ride. The investigators concluded:

“Staff at the activity centre made no effort to understand or consider the capabilities of the residents, and neither party had considered the overall suitability of the trip, or how to deal with an emergency.”

5. Government

Government bodies have an important role to play in supporting safety of outdoor, travel, experiential and adventure activities.

They can do this through financially and logistically supporting the work of governing bodies and industry associations, overseeing the quality of governing bodies, and developing Approved Codes of Practice. But a main way that government advances safety is through law and regulation.

National adventure safety regulation

In 1995, following the drowning of four children on a boating trip in Lyme Bay, the UK Parliament passed the world’s first national-level adventure activities safety legislation.

This law and its associated regulations require certain adventure activity providers to pass an audit demonstrating they meet safety standards such as:

- Positive safety culture

- Safety communications

- Sufficient numbers of competent instructors

- Competent safety advisors

- Appropriate instructor-participant ratios

- Availability of sufficient and well-maintained safety equipment

- A written emergency plan, including a plan for water activities “designed to allow the recovery of participants from the water before their life is threatened.”

Once the audit is passed, the organization can receive a license to provide adventure activities.

Roadford Lake Activity Centre held such a license. But the adventure activities regulations do not cover renting out an uncrewed motorboat. Consequently, the operation of the wheelchair-accessible boat was not audited as part of the adventure safety licensing scheme.

Regional and local boating regulation

Similarly, as a non-passenger vessel operated on a hire basis on an inland lake, no regional regulatory authority guidance or codes of practice governed the activities of the wheelchair-accessible boat. And no local authority licensing requirements applied.

Charity Commission

Both SWLT and WBT are registered charities in the UK. This means they are subject to the requirements of the Charity Commission for England and Wales, which regulates charities.

The Charity Commission is responsible for ensuring charities meet their legal requirements. However, the Commission does not exercise oversight of activities provided by charities. As a consequence, the Charity Commission is not positioned to effectively and proactively ensure good safety management of SWLT’s boating activities.

Investigators noted the Charity Commission has “no mechanism to ensure that SWLT was competent to safely deliver the charitable activity.”

6. Outdoor Industry

The outdoor and adventure sector has a role to play in safe management of outdoor excursions. National governing bodies (peak bodies) and industry associations can provide activity leader training and qualifications schemes, organizational accreditation, good practice guides and codes of practice, professional development opportunities, and other resources.

The United Kingdom has some of the world’s most well-developed outdoor sector bodies, including training organizations for myriad outdoor activities, activity leader certifications, written industry standards and an adventure activity Accepted Code of Practice.

Nevertheless, the incident brought forward gaps, particularly with respect to providing boat rental for adaptive boating activities for persons with disabilities.

Wheelchair-accessible boats

The Wheelyboat Trust provided a wheelchair-accessible boat to the Roadford Lake Activity Centre, with the requirement that the Centre send an annual condition note to WBT.

However:

- There was no evidence the Centre sent annual condition notes in the 10 years the boat was at the Centre.

- WBT took no action following the failure of the Centre to provide the updates.

The Trust also sent a survey in January 2021 to the Centre’s parent organization, South West Lakes Trust. The survey asked about the boat’s condition, including whether it was safe and seaworthy, whether the bow door seals were in working order, and if operators required a replacement manual.

However:

- The Trust did not respond to the survey.

- WBT took no action following the failure to provide a response.

The boat owner’s manual implied that WBT should be notified of boat modifications that changed safety characteristics of the boat. Multiple changes were made to the boat, with potential implications for safety. WBT did not prompt the Centre for information on modifications.

The report noted that WBT did not provide “any form of audit or inspection regime” to help ensure safe operation of its boats.

WBT is a small organization of just two staff, conceived as a passion project by a person who wanted his newly wheelchair-bound friend to be able to continue fishing. Staff have a focus on fundraising to cover the costs of boat manufacture, so boats can be provided at low or no cost to activity providers.

The work of WBT is honorable and admirable. However, the design, manufacture and provision of boats for outdoor recreational use comes with risks. WBT failed to enforce the safety requirements it established.

Boating

The RYA (Royal Yachting Association) is the UK’s national governing body for motor cruising, sportsboats and other forms of boating and sailing. The organization promotes safe boating practices through a network of more than 2,400 recognized training centres in over 58 countries.

The RYA has numerous safety resources, and a Safety Management Policy and System that includes a safety management policy statement, establishes safety objectives, and an accident and incident reporting system. This risk management infrastructure is designed to help its clubs and event organizers:

- Identify who is accountable for and responsibility for safety

- Record and publish policies and procedures

- Analyse hazards and risks

- Determine appropriate mitigation measures

- Review when conditions and circumstances change

Roadford Lake Activity Centre was an RYA accredited training centre for the provision of dinghy, keelboat, windsurfing and powerboat courses. However, the wheelchair-accessible boat was not covered by the RYA accreditation regime, and so was not included in audits or inspections.

The absence of any relevant government regulatory body or outdoor industry association providing effective oversight led investigators to conclude, “there was no external oversight of Roadford Lake Activity Centre’s management of the boat’s operation or condition.”

7. Incident Management

Dealing with mishaps involves, at the outset, taking reasonable and prudent steps to avoid an incident’s occurrence in the first place.

When an incident occurs, good management requires that:

- A plan to effectively mitigate loss and begin recovery is in place

- The plan is communicated

- The plan is rehearsed

Investigators found that the Activity Centre and Burdon Grange had not effectively planned to prevent emergencies, for example by considering alternatives to having a non-certified boat operator take passengers strapped into heavy motorized wheelchairs, from which, due to their disabilities, they would be unable to extricate themselves in an emergency, into the middle of a 730 acre (1.9 square mile) lake, in a poorly maintained and leaky boat.

Nor was there a well-developed plan, let alone an effective plan that had been communicated to those who might need to put it into place. Investigators stated:

“Neither the activity centre nor Burdon Grange understood the hazards present nor the risk that the boat trip posed to residents. There was no emergency plan, no consideration of what might happen if a resident were to enter the water, and no understanding of the actions the carers might be expected to take.”

The MAIB report described the boat flipping over, noting “the rapid capsize and inversion resulted in the immediate immersion of everyone on board.” Investigators concluded:

“Two of Wheelyboat 123’s six occupants were strapped into their motorised wheelchairs, which promptly sank to the bottom of the lake following the boat’s capsize, making any attempt at immediate rescue impossible, and resulting in their deaths.”

8. Risk Management Committee

A Risk Management Committee—sometimes called a Safety Committee, or Health and Safety Committee, or by other names—can provide an opportunity for an organization’s staff, or external persons, to pause from their day-to-day activities and deliberately, proactively consider how to improve safety outcomes at an organization.

South West Lakes Trust had a health and safety committee, which regularly met twice a year, and kept minutes, which were reviewed by the Board of Trustees. A regular agenda item was a report of recently completed safety audits.

The committee had the opportunity to uncover the numerous safety lapses that—if brought to light, and addressed—could have prevented a tragedy.

And yet, somehow, the committee did not design its activities to be sufficiently proactive, searching and vigilant to ask and answer the question: Are we the best we can be?

9. Medical Screening

Medical screening involves understanding the medical circumstances of potential activity participants, and taking steps to ensure they are medically well-suited for the activity.

This can involve insuring that special equipment (such as glucagon pens or spare insulin cartridges) or information (such as an Asthma Action Plan) comes with a participant.

It can involve ensuring that activity leaders and care attendants have the skills and knowledge to manage risks and provide care relevant to the participants’ medical needs, in the outdoor or adventure setting.

It can involve modifying activities, or in the most extreme cases, medically rejecting individuals from participating in activities.

In this case, Burdon Grange—who knew the medical condition of its residents—and the Activity Centre, which knew the risks of motorboat activities—appear to have had an overlapping, or shared, health and safety duty regarding the residents.

In day-to-day circumstances, Ali and Alex, who both had significant physical disabilities, were strapped into their heavy motorized wheelchairs for their personal safety.

However, neither of them had the capability to release themselves from their wheelchair.

Careful consideration of how to manage the risks of a person strapped to a heavy object, from which they could not detach themselves, while on a boat, is necessary.

However, the report found that:

“Neither the activity centre nor Burdon Grange had considered the risks that this introduced to their excursion on Wheelyboat 123. In addition, there had been no consideration given to what would happen in an emergency or if either of the residents entered the water.”

Could strapping be modified to allow quicker separation? Should staffing have been different? Should the activity have been restricted to closer to the shore, or to lower speeds or in lesser wave conditions? Should a different boat have been used? Should qualified boating professionals employed by the Centre have operated the boat?

There are no easy answers. And it’s important that persons of any level of ability have access to outdoor adventure and experiences in nature. These experiences carry inherent risk, which must be balanced against the benefits of the activity.

The report, however, concluded:

“Prior to the trip on Wheelyboat 123 no attempt had been made to evaluate this balance or reduce the risk to the residents.”

The issue of strapping persons down on watercraft previously arose, following the 2006 death by drowning of Virginia Yates in New Hampshire USA. The local rescue squad, called to assist Ms. Yates, strapped her onto a backboard and rescue litter, which in turn was strapped to a boat, in order to transport her from a private boat dock to a nearby public dock with vehicle access. The boat was swamped and sank a few seconds after leaving the dock, killing Ms. Yates. Rescue squad members had inadequate training on the boat, and were unfamiliar with the weight limits of the boat, which was overloaded, and there was a lack of standard operating procedures.

The reason Ms. Yates called for assistance? She had twisted her ankle.

Following this incident, emergency medical training curricula emphasized the need to avoid strapping patients to heavy metal objects while on boats.

10. Risk Management Reviews

Research in regulatory system design suggests that self-regulation is relatively ineffective in fostering positive safety outcomes. The incentives and the accountability are just too weak.

Having a third-party safety audit, however, comparing an organization’s safety practices against well-established standards, can propel a higher level of safety performance.

(Internally conducted risk management reviews, when performance is compared against rigorous, documented performance standards, by competent and impartial persons, can also be valuable.)

South West Lakes Trust did have an independent auditor assess the organization’s compliance with health and safety regulations, which was included in a report sent to the Charity Commission.

Regulatory requirements, however, are often fairly broad, and evaluation of regulatory compliance may lack the attention to detail of audits that specifically evaluate the practices of outdoor and adventure programs against industry-specific standards.

The auditors did not find any inconsistencies in their report for the year ending January 2023.

Certain adventure activities conducted on a commercial basis for young people in the UK are subject to adventure safety regulations, which involve passing a third-party audit as a condition of licensure. South West Lakes Trust underwent and passed this audit. However, wheelyboat operations fell outside the scope of the regulations, and so were not evaluated.

The Wheelyboat Trust sought to audit the safety performance of those with whom it had placed boats, but failed to follow up when audit information was not received.

Roadford Lake Activity Centre was an accredited RYA training centre. But, as with the Adventure Activities Licensing Authority, which oversees the UK’s statutory adventure activities audits and licensing scheme, the wheelyboat fell outside the scope of RYA’s audit activities.

Other options are available to adventure providers in the UK, such as the voluntary Adventuremark safety accreditation scheme for providers of adventurous activities that fall outside the scope of the Adventure Activity Licensing regulations.

And the UK is bristling with experienced outdoor professionals who offer skilled safety audit services to outdoor and adventure programs in the UK and beyond, for those willing and able to pay.

While the numerous audits South West Lakes Trust went through show a real attention to quality and care, the nature of the outdoor and adventure safety auditing structures required of—or even available to—the organization left a wheelyboat-sized gap.

11. Documentation

In the context of adventurous, excursion-based and outdoor recreation/education programs, documentation serves two core purposes: to identify what should be done, and to establish what has been done.

We’ll focus here on the former.

These documents—such as SOPs, owner’s manuals, risk assessments, inspection checklists, and training curricula—help individuals know what they are supposed to do, and how to do it.

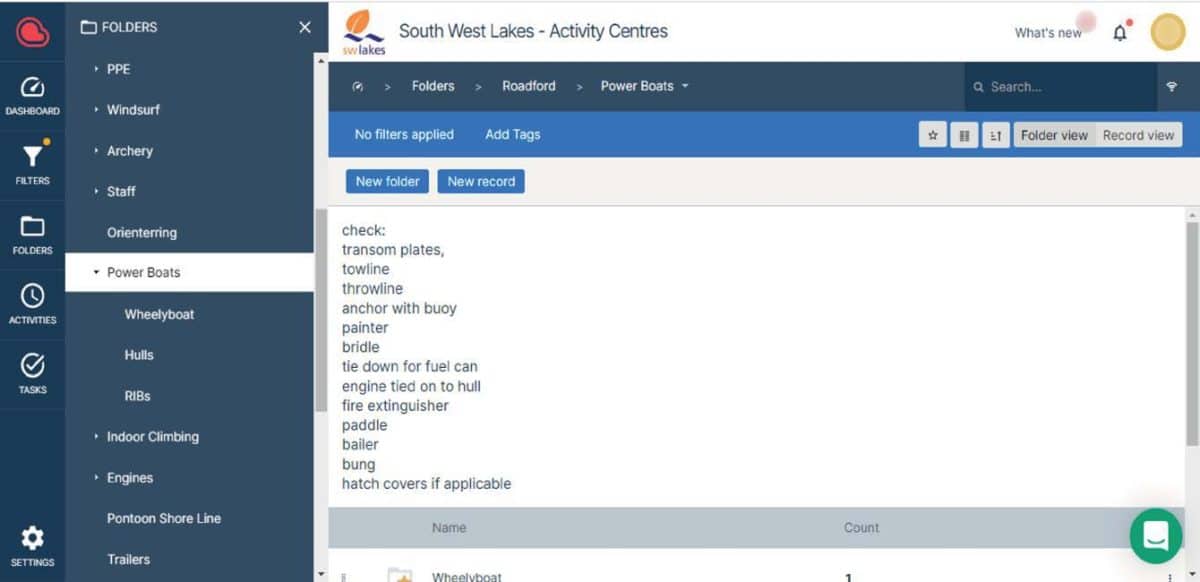

South West Lakes Trust had a set of documents, along with an electronic data management system recording maintenance information.

However, Marine Accident Investigation Branch personnel identified gaps in the organization’s documentation.

The boat owner, The Wheelyboat Trust, provided a copy of the boat owner’s manual to Roadford Lake Activity Centre—once when delivering the boat, and then again by email in 2016. At the time of the investigation, the Centre was unable to locate either copy of the manual.

Also in 2016, after an incident involving the capsize of another wheelyboat where water ingress into a buoyancy tank caused the boat to capsize, WBT sent instructions to evaluate buoyancy tanks each month for water leakage into the tanks. Maintenance documents were not updated with this requirement—and there was no evidence those checks were conducted.

The boat owner’s manual stated that lifejackets—not buoyancy aids—should be worn by everyone aboard the boat. This was not reflected in the Centre’s documentation, which implied that wearing buoyancy aids might be acceptable.

The boat was delivered to the Centre with safety notices and the boat builder’s plate in place. These documents, which contain important safety information, disappeared at some point, and were not replaced.

The boat was delivered to the Activity Centre, subject to a placement agreement between the Centre and WBT. A signed copy of the agreement could not be located at the Centre’s offices or SWLT’s headquarters.

The agreement required the operator to take responsibility for safe operation, maintenance and upkeep of the boat. The operator also agreed to submit annual condition notes to WBT and to:

- Regularly check and replace as necessary the bow door seals, winch rope and winch

- Regularly clean the exterior and interior of the wheelyboat

- Promptly repair damage

- Keep accurate records of repairs and servicing

- Regularly service the wheelyboat

SWLT did not submit the condition notes, or maintain repair and servicing records, as agreed.

WBT sent a questionnaire to SWLT in 2021, asking about the boat’s condition, including whether it was seaworthy and safe, whether the organization needed a replacement owner’s manual, and if the bow door seals were working properly. WBT never received a response.

Incident analysis indicated that as the boat tilted to the side, the two heavy motorized wheelchairs slid across the wet deck, further destabilizing the boat and hastening the capsize.

Brakes were applied to the wheelchair wheels, but the wheelchairs were not otherwise secured, and the brakes were insufficient to stop the wheelchairs’ slide across the deck and then overboard.

The owner’s manual identified opportunities for more secure attachment to handrails or solid strapping points, and encouraged operators to consult with WBT for advice about additional securing options.

But with the copies of the owner’s manual lost, this guidance was unavailable to Activity Centre staff.

Investigators concluded:

“The use of wheelchair brakes alone might have been appropriate for smaller manual wheelchairs…however, each of the motorised wheelchairs…exceeded 100kg. Staff and instructors at the activity centre had not recognised the risk and potential consequences of unexpected movement of such a weight, or considered whether additional securing was required. Without access to the wheelyboat owner’s manual, or awareness that the WBT could be contacted to discuss additional securing, there was nothing to prompt them to reconsider the arrangements.”

The owner’s manual also documented a maintenance routine, which included periodically inspecting the bow door seals for deterioration, and checking buoyancy chambers each month for water ingress.

The investigative report summarized documentation deficits this way:

“Over the years of operation at the activity centre, Wheelyboat 123’s owner’s manual, builder’s plate and safety notices had been lost, and the centre’s documentation did not capture the important safety considerations when operating the boat.”

12. Accreditation

Roadford Lake Activity Centre was accredited by RYA—and passed an inspection in 2021. However, the wheelyboat was not evaluated, as it was not used for RYA authorized activities.

As with Risk Management Reviews, above, there was not an accreditation scheme for the Activity Centre that would address wheelyboat safety, and where the value and benefits of such accreditation outweighed the cost and burden of gaining accredited status.

13. Seeing Systems

When a tiny, startup outdoor organization suffers a safety incident, it’s easy to find fault. There is often an absence of established safety procedures and well-developed documentation. Resources are tight, and safety systems are not elaborate.

The same is true for adventurous activity providers in low-income countries, where financial constraints and relaxed social norms around safety may lead to less rigorous practices.

But South West Lakes Trust is a 5 million pound organization, founded in 2000. It’s in a high-income country, stuffed with training bodies, qualifications schemes, and adventure safety specialists.

And it’s a charity, dedicated to serving people, not maximizing profit.

So a safety failure like the capsize of Wheelyboat 123 is harder to explain.

But managing risks is hard.

Incidents occur in the context of the complex sociotechnical system that is led outdoor activities. It’s extremely difficult—or impossible—to completely eliminate human error.

In a well-established and well-intentioned organization, such as South West Lakes Trust and its subsidiary Roadford Lake Activity Centre, serious incidents are often unanticipated.

They come as a terrible shock, to an organization’s staff, who may sincerely believe that they were doing all the right safety things.

This is where systems thinking can help us make further steps to reduce the likelihood and severity of incidents.

Basic tools like risk assessments have an important place in good risk management, when appropriately used. But additionally employing a safety infrastructure designed with the complex sociotechnical system of led outdoor activities in mind can lead to even better safety outcomes.

In a complex system, we may not be aware of all the risks—such as a person’s attitude towards safety, or a sudden change in weather, obscure symptoms of a serious medical condition, or an unknown defect in equipment.

And the risks may always be changing.

And the interventions we take in the safety system—stopping for a half-hour on the snowy trail to fix a hiker’s backpack—may lead to unanticipated outcomes, such as mild hypothermia in another group member.

Systems thinking teaches us to see breakdowns in the safety system as inevitable. We just don’t know when, or where.

And so systems-based risk management infrastructure will have redundancy in safety structures—so if one element fails, another is there to prevent calamity. Two competent instructors leading the wilderness trip. Double checks of the climbing harness. Internal risk management reviews, plus external risk management reviews, plus an accreditation-based safety audit.

And resilient safety systems are characterized by a having a reasonable amount of extra capacity on hand—physical, intellectual, or otherwise.

(Building in excessive amounts of additional capacity, however, increases costs, which can harm business sustainability, or make outdoor adventure only accessible to the privileged.)

Would having a permanent member of staff at South West Lakes Trust dedicated to the maintenance and condition monitoring of Activity Centre craft have made a difference on that breezy June day in 2022?

Would an additional investment of completing a recognized disability awareness training, on the part of SWLT instructors and support staff, help prevent future tragedies?

Marine Accident Investigation Branch officials thought so. They recommended these investments, among others, in their report.

Would a change in RYA’s audit scheme to cover motorboat hire, such as with the wheelyboat on Roadford Lake—or the advancement of some other accreditation and audit scheme—have caught the maintenance defects, opaque to Centre staff, but glaring in hindsight?

Perhaps.

Would a change in the regulatory context—with boaters required to meet safety standards—propel the additional skills, procedures or other capacities to help future boaters enjoy Devon’s beautiful, sparkling lakes without harm?

MAIB may believe so.

MAIB’s Chief Inspector of Marine Accidents said:

“As well as the catalogue of failings highlighted by the report, the investigation has also uncovered a worrying lack of oversight which must be seen as an impetus for urgent action. Charitable activities such as this seem to fall into a grey zone with no organisation or authority in a position of oversight. This meant that no-one stepped in to question what had become custom and practice. Addressing this is not simple and may only be possible with a change in the law; however, the current situation is not something that should be tolerated.”

Changes at all levels of the system—to the training of in-the-field personnel, to the administrative practices of the organization, to the certification and accreditation schemes of industry bodies like the RYA, to reasonable requirements put in place by government bodies—when combined, can match the complexity of the complex sociotechnical system in which incidents occur, and powerfully improve safety outcomes.

This is systems thinking, applied to safety.

Reflection

A long-standing organization with a suite of safety tools including procedures, documents and safety audits experienced a tragedy taking the lives of two care home residents out to explore the pleasures of Roadford Lake.

The organization specialized in water activities, and had layers of management and governance—from activity instructors and the Chief Instructor role, to visitor experience managers, Director-level administrators, and the CEO and Board—to support safety.

All this came crashing down on a late spring day in 2022.

In addition to the MAIB analysis, the incident is subject to a criminal investigation, and Devon and Cornwall Police, the Health and Safety Commission, and the Care Quality Commission have all launched investigations.

It’s reasonable to think that Roadford Lake Activity Centre staff felt their risk management practices were adequate, that they genuinely cared for the well-being of visitors, and that staff believed all reasonable steps were being taken to provide fun, safe trips on Roadford Lake.

If you are associated with an outdoor, adventure, experiential or travel program, how do you evaluate your organization’s safety practices? Are risks being reduced so far as is reasonably practicable? While incidents will inevitably occur, will they be simply due to the inherent risk that is part of outdoor adventure?

Conclusion

Alison Tilsley and Alex Wood were much-loved members of their community. Ali’s family said, “She was loved by everyone who ever met her.” Her family members remembered her quick-witted humor, the clever nicknames she created for her friends, and her enduring positivity.

Many people—the adaptive-sports advocates at The Wheelyboat Trust, the managers at Burdon Grange who believed in providing nature-based recreation opportunities for residents, and the outdoor activity professionals at Roadford Lake Activity Centre—worked hard to make fun and positive outdoor experiences possible. But more work remains to be done.

Outdoor experiences offer joy, wellness, appreciation for nature, health, life skills, and more. When we seek to improve the safety and quality of those experiences, and help more people have life-affirming and safe adventures in the out-of-doors, we are helping do that work—and in that way, we can honor the memory of Ali and Alex.