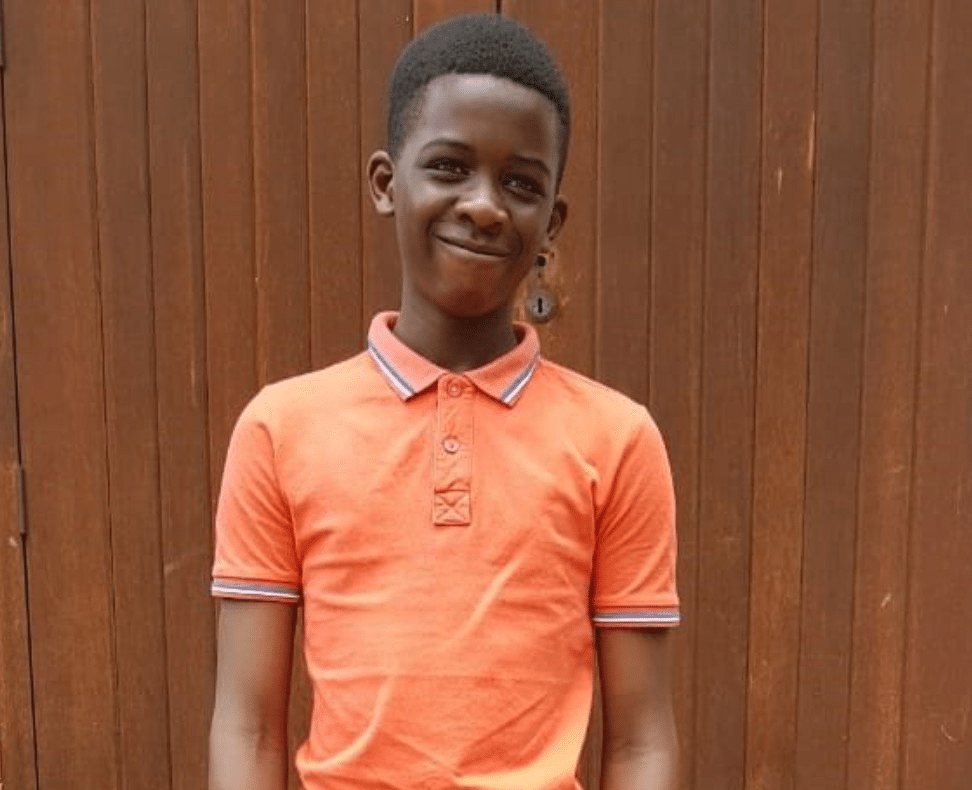

Enock Mpianzi, 13, Drowns in Crocodile River on School Outing at South African Orientation Camp

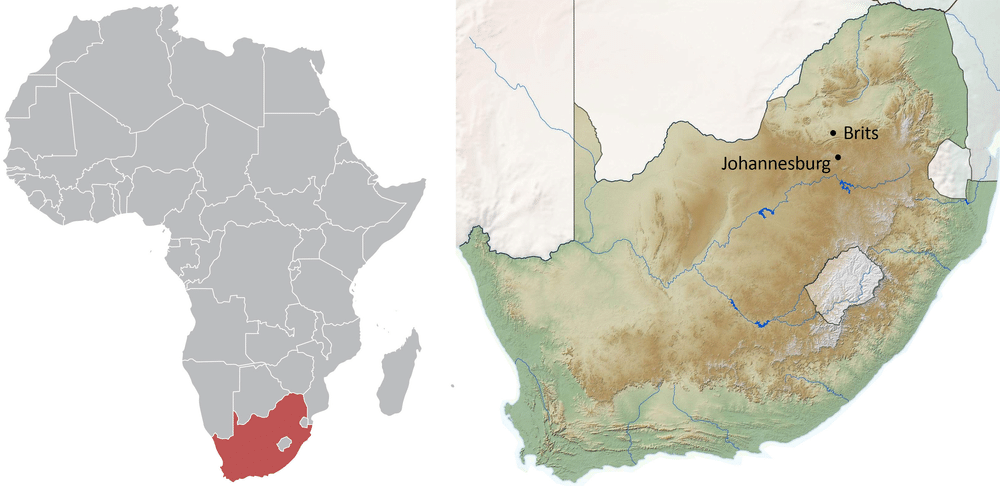

Enock Mpianzi’s father got a call from Parktown Boys’ High School in late November 2019, telling him that his son had been admitted to Grade 8 at the school. Staff at the elite boarding school, outside Johannesburg South Africa, informed him there would be a Grade 8 camp in January that his son would be expected to attend.

The three-day camp experience, at a lodge adjacent the Crocodile River, was to offer outdoor adventures to build cooperation and teamwork, and help ease the transition for new students to the school.

The outdoor education program started January 15, with a “river swim” on the agenda. The following day, Enock’s father received another call from the school. The school principal said Enock was missing. A search of the river was underway.

The next morning, police divers found Enock’s lifeless body.

Parktown Boys’ High School, one of the oldest schools in Johannesburg, had been organizing outdoor education experiences for years. The program provider, Nyati Bush and Riverbreak resort and lodge, had been operating for decades. How could this tragedy have occurred?

Day 1: Misadventure

The first day of the camp started early, with a student assembly at the school. A roll call was conducted of all 214 Grade 8 boys, and around 11 am, 202 of the students (those who had agreed to go to the camp and who had paid the fee) boarded a bus for the camp. Accompanied by seven educators and the school principal, they drove off to the venue, some three hours away near the town of Brits, in the North West Province. It was the first day of the school year.

On arrival at the camp, the learners had lunch, and were divided into 15 groups. Their first activity was at the rugby fields, where they were instructed to build a stretcher out of bamboo poles, and then race with them, role-playing an emergency drill, to the river.

Some of the bamboo poles broke, and students resorted to using their shoelaces to secure them together. Eventually, learners completed the stretcher-run adventure to the river.

Once there, the learners were told to strap their make-shift stretchers to black, doughnut-shaped inflated tubes to form a raft. One learner was to act as the injured patient, and the others would transport them down the river.

No personal flotation devices (PFDs) were issued. Nor could they have been for all 202 learners: the facility only had 12 PFDs on hand.

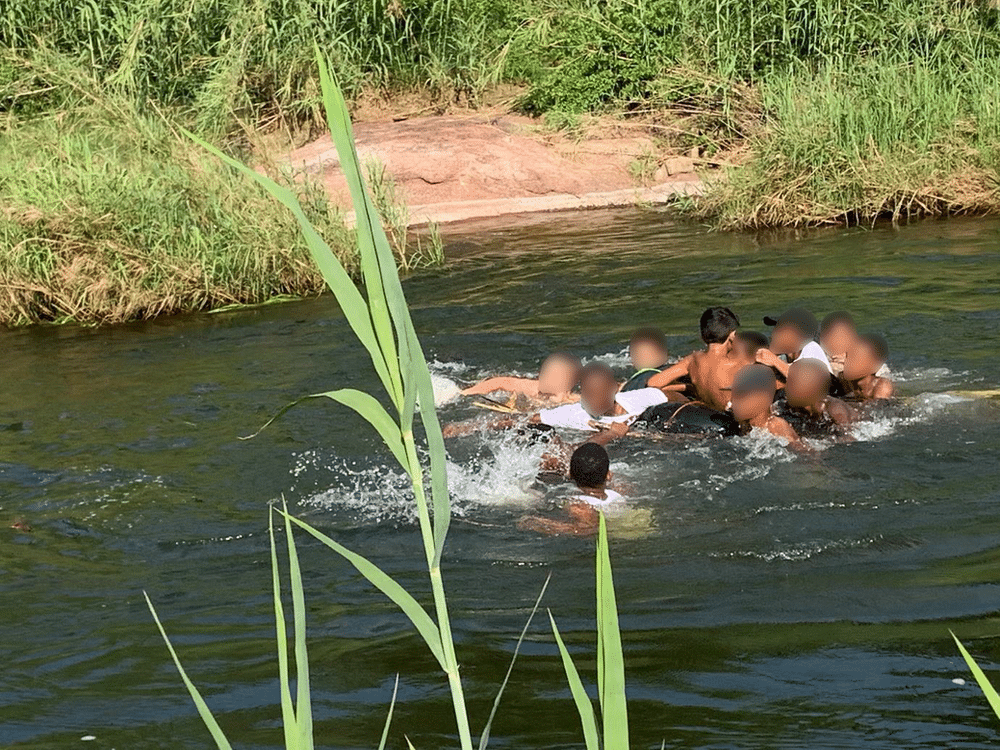

One of the learners in Enock’s group reportedly said their improvised stretcher capsized minutes after they got into the water. The boys scrambled to grab onto parts that came loose. Some were able to hang on to one of the inner tubes, using their free arm to paddle.

“At that moment, I felt like I was going to die,” he said.

“Enock did not manage to get to the rubber tube,” the learner continued. “He seemed stuck in one place, trying to keep his head above water. I grabbed a pole and tried to pass it to Enock. But…I couldn’t reach him…the river swept him away.”

The students reportedly called out for help, but no adults were in sight. School staff had stayed up by the rugby fields while the last learner groups were finishing up there, so weren’t at the river when learners entered the water. The Grade 8 head was extremely busy, off dealing with an issue of insufficient halal food being delivered.

Multiple rafts had broken apart. Learners, some of whom did not know how to swim, were scattered along the fast-flowing river. “The current was way too strong,” said one learner. “Everyone was panicking.”

“We tried to grab on the reeds on the side of the river,” a different learner stated. But the river was moving very fast, he continued, and “the current pushed us away.”

Another learner said, “The moment I got caught up in the current, I realized that the current was way too strong…I was so scared.”

“Everything was going wrong,” he said.

The boys clinging to the inner tube were swept along a bend in the river, and lost sight of Enock.

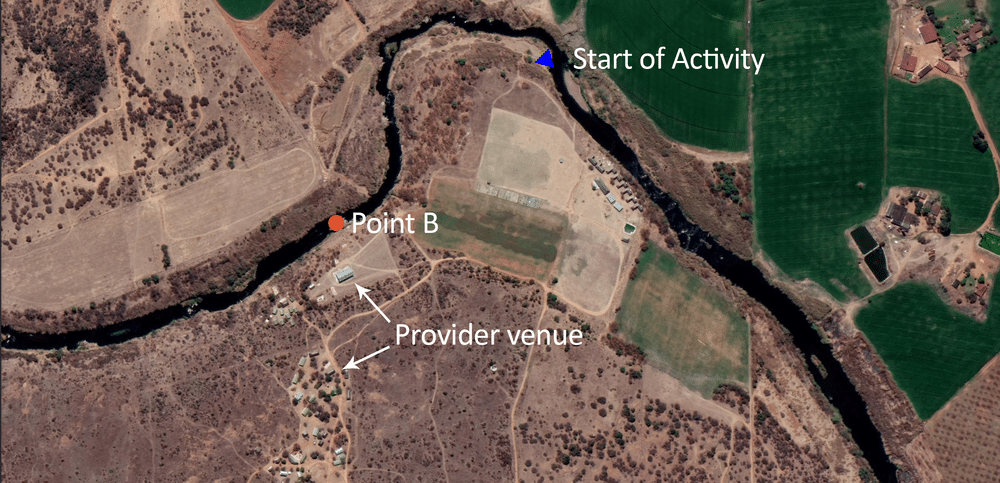

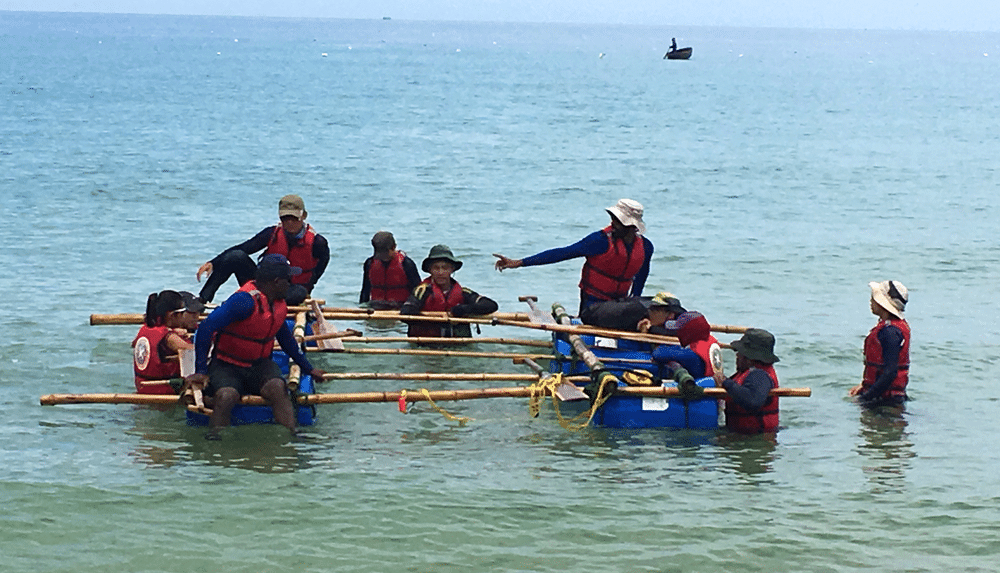

Learners in the Crocodile River with their raft, on the day of the incident.

One learner, who made it to shore, found a facilitator, and told her there were people struggling in the water. He asked her to help. She responded that she could not swim. She called another facilitator on her phone for help.

Eventually, adults helped pull learners, some swept far downstream, to shore. Other learners were stranded on an island in the river, and were rescued by facilitators. The boys returned to the camp, where the principal wanted to take a roll call. But the list of learners had been left on the bus, which, after dropping off the students, had immediately departed back to Johannesburg. And no rosters for individual small groups had ever been made.

One of the educators called the driver of the bus around 3:30 pm, to retrieve the list. The driver indicated they were not in a position to return to the camp to deliver the list.

The school was contacted directly, and emailed a list to the camp. From there, it was printed and provided to school staff on site. A roll call using this list was conducted around 5:30 pm.

But the roster that was sent by the school listed all incoming Grade 8 learners, not just the ones who had departed for the camp. When the names on the list were read out, 11 learners—including Enock—were not present.

School staff, recognizing their roster was not the list of those attending the camp, assumed that the missing learners were simply boys who were not participating in the outdoor education experience.

A learner reported Enock missing, it was alleged, but the report of Enock’s disappearance was allegedly dismissed.

The boys went on a hike. They had dinner, and then left for a sleepout in the veld.

Day 2: Enock’s Absence Noticed

The next morning, the learners continued with team activities, as per the program agenda.

School staff at camp took a photograph of the list of 11 missing learners and sent it to the school’s enrollment office. On the morning of day two of the camp, Thursday January 16, the enrollment office began calling the parents of those 11 learners, asking if their son was attending the camp.

Around 11:45 that morning, the enrollment office called school staff at the camp, and said that Enock’s parents confirmed he was an attendee of the camp.

Another roll call was held, around 2 pm that afternoon. Enock’s absence was confirmed. A search found that Enock’s bag, containing his personal items, was at the camp.

It was only then, some 24 hours or more after Enock was last seen, struggling to stay afloat in the Crocodile River, that it was clear that he was missing.

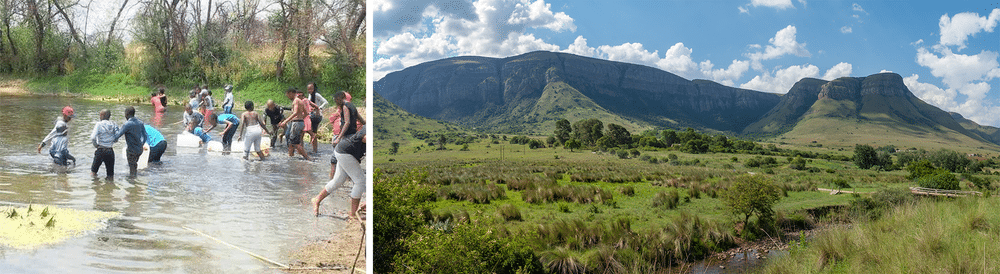

The provider’s venue. Image credits: Independent Online (UL), Travelground (LL, UR), News 365 (LR)

Once it was evident that Enock was missing, South African Police Service emergency personnel were notified. SAPS search and rescue teams began combing the river and surrounding areas.

Around 4 pm, Enock’s parents were called and were informed that he was missing. The school transported them and some accompanying relatives to the camp; they arrived around 9 pm.

It wasn’t clear exactly when or how Enock had disappeared—during the river activity or the campout in the bush. One of Enock’s relatives suggested a photo of Enock be posted on social media, and the school did so.

Enock’s father asked for his son’s bag. He found Enock’s pillow and blanket there, suggesting that he was not part of the campout in the veld.

The search, which had been ongoing throughout the afternoon, was eventually halted by darkness.

Day 3: Enock’s Body

The following morning, Friday the 17th, the search resumed. Around noon, SAPS Search and Rescue notified Enock’s parents and school staff that Enock’s body had been located.

His body was reportedly found 1.8 kilometers downstream.

Framed photo of Enock Mpianzi from his funeral service, February 1, 2020. Credit: Gallo Images/Daily Sun/Morapedi Mashashe

The Investigation

Parktown Boys’ High School is a public boarding school in the South African province of Gauteng. The Gauteng Department of Education, which oversees the school, commissioned a forensic investigation of the incident.

Investigators cited a number of failures that led to Enock’s drowning. They made a series of findings and recommendations regarding:

- The school, Parktown Boys’ High School;

- The provider, Nyati Bush and Riverbreak;

- The province’s Department of Education, and

- Federal school safety regulations.

Findings

The investigator’s report documented nine findings. These involved issues with participant rosters, staff-to-learner ratios, learner supervision, PFDs, missing student notification, permission to conduct the outdoor activity, GDE’s permission system, venue safety history, and the school’s safety history. Findings, in italics, are followed by commentary.

Finding 1: Improper roll call procedures

The investigation noted that an accurate participant roster was never made; instead, another list was used, and incorrect assumptions were made about missing participants.

Rosters were never made for the small groups of learners, and small group leaders never performed checks to see if their entire group was present.

Finding 2: Improper staff-to-learner ratios

Having only seven educators at the camp (plus the school principal)—about one educator for every 25 pupils—provided an insufficient supervision ratio for 202 learners.

In many outdoor education settings, a ratio of one chaperone for each group of 7-15 learners, in addition to the presence of trained facilitators/outdoor educators, is typical.

Finding 3: Inadequate learner supervision

The program provider supplied too few facilitators, at least one of whom couldn’t swim, and they provided poor safety management.

School staff should have been on site for the water activity, and actively supervising. They should have promptly stopped the water activity when the lack of facilitators and PFDs was evident.

Let’s look first at the finding of inadequate supervision from the provider, Nyati Bush and River Break—and their communications on this topic.

Seven days after the incident, the provider released a statement to the news media. The provider stated that “internal standard emergency procedures were immediately instituted by the camp management.” The statement faulted the school for lapses, and blamed students for creating “a dangerous situation.”

However, the investigation revealed that the provider was far from blameless. Not only did the provider fail to provide sufficient qualified staff and institute appropriate safety procedures, but the provider showed a lack of awareness about the activity site and the nature of the incident.

The provider stated to investigators that the entire water exercise took place in shallow water and on dry land. However, when it was pointed out by investigators that learners had been stranded on an island in the river and had to be rescued by facilitators, the provider’s representative responded, “I don’t know about islands.”

In addition, investigators faulted the provider for their responses to investigation queries.

Nine days after the incident, investigators conducted a site visit of the incident location. The provider told investigators that the river level on the day of the incident was about a meter lower than when observed during the site visit. However, photographic evidence contradicted this. Investigators wrote that the evidence given by the provider was incorrect and could “be viewed as an attempt to mislead” investigators.

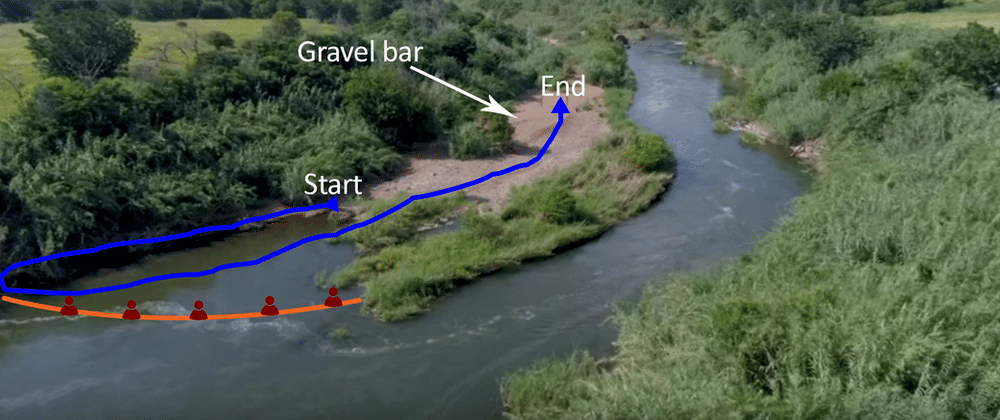

The provider also stated that the water activity consisted of learners taking their stretcher across dry land on the shore of the river to a promontory, then back through shallow water and over a gravel bar to an end point. Five facilitators, the provider stated, were situated between the shallow water and the main flow of the river, to keep learners out of deep water. No learners, the provider stated, went farther downstream than the gravel bar.

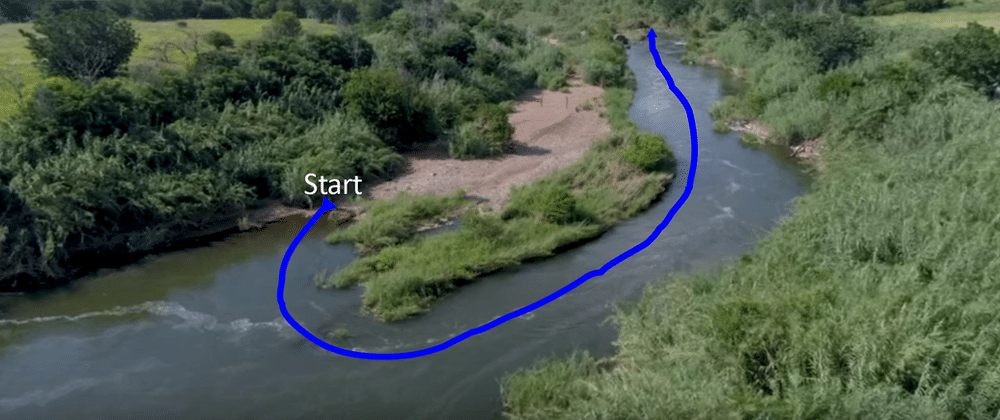

The provider’s description of the activity to investigators. The blue line indicates provider’s claimed route. Maroon icons indicate claimed facilitator locations. Photo credit: Carte Blanche

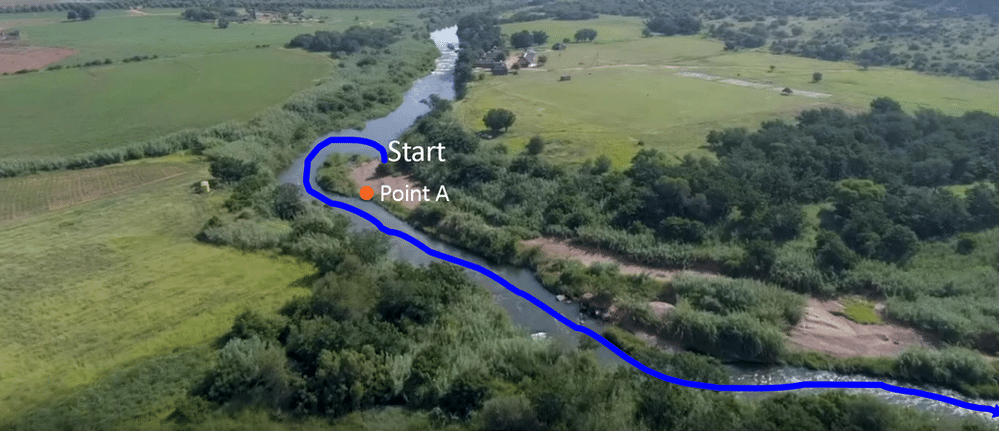

However, investigators determined that instead, learners were told to enter the river and go downstream, and that no facilitators were situated to stop learners from entering the deep, fast-moving water. Instead of stopping at the end of the gravel bar, investigators established that learners were swept downstream, and rescued all along the riverbank, much farther down the river from the gravel bar.

The actual activity, per investigator findings. Learners went downstream past the end of the blue line. Photo credit: Carte Blanche

The version of the incident put forward by the provider, investigators said, “is false.” The provider’s explanation that learners were supposed to stay in shallow water (and that life jackets were not issued for such shallow water activities) is “callous and false,” investigators stated.

The provider, investigators stated, “lied” to them repeatedly: the provider lied about the activity route, lied about facilitator placement, and lied about where learners ended up downstream.

The investigators found that the provider “attempted to mislead” investigators by putting forth a version of events that would minimize the liability of the provider and “would deceive” investigators.

The investigators wrote that they found the provider’s “misrepresentation and presentation of false evidence to be scandalous and offensive.”

One principle of risk management is to ask one’s self, when undertaking an activity: “How would I look if I were justifying this to legal authorities, newsmedia or investigators?” If the activity is hard to justify, then perhaps it should not be done. When providers engage in this kind of thinking, and groups retain only providers who do so, safety outcomes are improved.

Instead of stopping at point A, learners were swept far downriver, including all the way off the map at the bottom right corner. Photo credit: Carte Blanche

Learners were swept down to as far as Point B. Photo credit: Google Earth

Let’s also look at the finding of inadequate supervision from the school.

Investigators said that school staff should have been on site for the water activity; this is clearly best practice.

However, investigators also said that school staff should have been actively supervising, and should have stopped the activity when inadequate facilitator presence and PFD usage was seen.

This raises the question of the roles, duties, and qualifications of school staff, as opposed to those of the specialist provider.

One of the educators stated that the water activity “looked under control.” But they acknowledged, “I’m not clued up on river safety…at that moment, I [didn’t] know what you do and don’t do in a river.”

The decision to use PFDs in an outdoor education setting depends on a number of factors, including depth of water, current, obstacles, visibility (e.g. night vs. day), assessed maturity of group, and swimming ability assessment. And evaluating the hazards of moving water is a complex skill taking study and practice to do well; underestimating risks of swiftwater is notoriously easy.

Attending educators have an obligation to use common sense, and to take reasonably practicable steps to prevent reasonably foreseeable harms.

School staff knew not all learners knew how to swim. Shortly after arriving at the river, one of the educators asked another, “I wonder if they know that not all the boys can swim?” The other educator responded by saying that thought that this was a good point.

Given that, the need for at least some learners to use PFDs should have been plainly evident to even untrained observers.

But it can be a matter of discussion as to the extent to which educators without special training in outdoor activities should be able to determine appropriate activity-specific procedures based on specialist knowledge and skilled assessments.

Finding 4: PFDs not used or sufficiently available

Learners should have been issued PFDs. Not doing so was “reckless in the extreme.” Enock’s death by drowning was foreseeable.

Finding 5: Learner notification of Enock missing

A learner alleged that he approached a facilitator to tell them Enock was missing. The facilitator allegedly was rude and dismissed him.

This assertion was widely reported in the press following the incident. Investigators attempted to speak with learners to corroborate the allegation, but had limited success in arranging interviews. Therefore, investigators considered the allegation to be unconfirmed.

Finding 6: School conducted camp without permission

The school did not get permission from the Gauteng Department of Education for the Grade 8 Camp to take place.

The school was required to apply for permission three months in advance to the Gauteng Department of Education, in order to offer the outdoor education experience to its learners. School staff submitted an application late. As they did so, they cited as a contributing factor that the facility they had booked earlier had suddenly backed out of the agreement to host the school camp.

The school never heard back from the GDE. Yet school staff decided to go ahead with the trip anyway. This was a clear violation of Regulation 8A(1)(b) of the Regulations for Safety Measures at Public Schools, requiring approval for trips.

It also points to the possibility of a cultural issue at the school, where rules are knowingly broken.

Finding 7: GDE handled trip permission incompetently

Permission for the school to take the Grade 8 learners to the camp was incompetently handled.

GDE’s process for approving school trips starts with submitting an application in person at a district office. The school representative fills in their details in a book and signs; a GDE intern also signs the book, indicating receipt of the application.

Parktown’s application was filed on November 19. But it wasn’t signed by the school person, or by a GDE intern. And the application did not go through the normal process. During the investigation, the application was found in the desk in an office of one of the interns, who was on a temporary assignment and put the application in a desk drawer. The application never reached the district director’s office.

It was understood by school staff that applications sent to the GDE commonly were not processed correctly. This was perhaps a contributing factor in the decision to proceed with the camp, even without GDE authorization.

The evidence of multiple, systemic breakdowns—a previous provider suddenly cancelling, knowingly violating safety regulations, a dysfunctional authorization system—can be seen as contributing to an overall system where risks are steadily compounded, and the likelihood of a tragic incident is magnified.

Investigators recommended that persons responsible for handling application processes be subject to discipline for their negligence. Two GDE staff were reportedly suspended for three months. While this may incentivize those two persons to avoid similar circumstances in the future, it may not be sufficient to address the underlying causes of GDE’s shortcomings.

The press reported that Gauteng’s head of education “promised that heads would roll for Enock’s death.” While punishing individuals may have a superficial appearance of addressing issues, the idea of Just Culture reminds us to seek out and address the underlying causes of errors and accidents.

Finding 8: Previous deaths at provider venue

Enock was the fifth child to drown at the provider’s facility since 1999.

Investigators asked the provider if there had been any other incident at the venue in the past. The provider said that a child died in a swimming pool there in 2008.

Investigators soon learned, however, that this was not the complete story. Two days after the provider described one fatality, South Africa’s biggest Sunday newspaper, the Sunday Times, ran a report about other deaths at the venue.

These drownings include:

Portia Sowela. Portia, a student at Northview High School, drowned in the river at the venue in 1999, while on a sports camp.

Reportedly, she was swept away by river currents during a water activity, and no one realized she was missing. Her body was found the following day.

Thuso Moalusi. Thuso Moalusi, a student at Malvern High School, drowned in the river at the venue in 2002.

Thuso was reportedly taking part in a swim by the river’s dam. A learner noticed he was clearly struggling to swim. Another learner tried to assist him as he appeared to be drowning, but was unable to do so safely, and “was forced to leave Thuso Moalusi to drown.” The educator on the site had told Thuso, who had complained of struggling to swim, that he must continue, and reportedly did not enter the water to attempt to rescue him.

Reportedly, Thuso’s death was not formally communicated to parents of learners at the school: there was no parent’s meeting or newsletter to parents informing them about the death. No investigation of the incident is known to have been made.

Thumi Mokomane. Thumi Mokomane, a student at Laerskool Welgedag, drowned in the swimming pool at the venue in 2009. Allegedly, as with Enock, he was missing for hours before the alarm was raised about his disappearance.

A written report on the drowning was created but was allegedly stolen from the school’s ‘strong room.’

Mellony Sias. Mellony Sias, a student at Hoërskool Adamantia, drowned in the river at the venue in 2010, while attending a training camp there with her school’s hockey team. Allegedly, her tube capsized in the river, and she was swept away by the current. Her body was found by a farmer, 10 kilometers downstream.

Investigators found the provider’s attitude “extremely problematic,” expecting greater care would have been exercised in the light of these incidents.

Investigators found it “shocking and disgraceful” that Enock was the fifth child to have drowned at the venue.

Given the provider’s fatal history, investigators found the provider’s failure to appropriately manage risks with the water activity to be “outrageous and reckless.”

The school did not appear to conduct a systematic assessment of the venue’s incident history prior to booking the provider’s services. Evaluating providers prior to hire is clearly an area where improvement opportunities exist.

Water activities in the Crocodile River, and the river downstream in Mpumalanga. Credit: IOL/Facebook

Finding 9: School failed to learn from past safety issues

The school failed to give serious consideration to recommendations from an investigation into past safety issues at the school.

The provider is not the only institution with a history of safety problems.

In September 2018, the school’s former water polo coach pleaded guilty to 144 charges of sexual assault against multiple Parktown pupils. He was sentenced to 23 years in prison.

Following that, teachers at the school were accused of making light of the scandal, making inappropriate comments directly to victims, and fostering a “culture of silence” inhibiting other abused learners from coming forward.

A teacher resigned after reportedly giving a “racist, threatening rant” (reportedly calling learners who came forward about victimization “evil” and “snitches”). Another was charged with assaulting a learner.

The law firm hired by GDE to lead the investigation into the sexual assault scandal delivered a 2018 report making recommendations to improve the safety of learners at Parktown Boy’s High School. The same firm also conducted the investigation into Enock Mpianzi’s death.

The 2018 report raised serious concerns about lack of supervision of learners by educators on camps. The report noted approvingly that the school stated that they had discontinued their Grade 8 camp. And yet, two years later, the firm was yet again investigating the school, finding that the Grade 8 Camp had in fact not been discontinued, and that lack of supervision was again a serious problem.

“Every possible measure should have been put in place to ensure that the health, safety and security of every learner was not compromised in the way it had been in the past,” the investigators wrote. The school, however, failed to do this, they said.

Flowers placed at the entrance of Parktown Boys’ High School after Enock’s death. Credit: IOL/Nokuthula Mbatha/African News Agency

Recommendations

The investigating entity is a law firm; accordingly, their recommendations are of a legal nature. Investigators made six recommendations: disciplinary action for individuals at the school, the Department of Education, and the provider; further investigating other deaths at the venue, regulating venues, and strengthening public school safety regulations.

Recommendation 1: Enact disciplinary measures for individuals at the school

Investigators recommended the school’s principal and certain educators be subject to disciplinary action for negligence regarding rosters, overall safety of learners, and other issues.

The school was found negligent for allowing the water activity to proceed, and the school’s governing board found negligent for inadequate oversight at the camp.

The principal was dismissed, but later reinstated.

Recommendation 2: Enact disciplinary measures for relevant Gauteng Department of Education personnel

The GDE as a whole was found negligent with respect to the granting of authorization for the camp. Investigators recommended that those responsible for the faulty authorization process be subject to disciplinary action.

Recommendation 3: Hold provider responsible for negligence

The provider was found negligent and reckless with regards to overall safety and care of learners, the nature of the water activity, and for the issue of PFDs.

Recommendation 4: Investigate other deaths at provider venue

It was noted that investigations of the four other drownings at the site did not all appear to have been completed, with appropriate follow-up conducted.

Consequently, investigations of those fatalities at the location were recommended, “to ensure that the interests of justice are served.”

Recommendation 5: GDE to regulate provider facilities to enforce safety standards

Investigators recommend that the province’s Department of Education regulate providers of school camps and similar programs, so as to enforce minimum safety standards at the sites.

This is the first recommendation that involves a sweeping move to set and hold outdoor education providers to safety standards. Punishing teachers for failing to ensure PFDs were worn will have limited effect. But instituting a well-developed regulatory mechanism across all program providers can, if done well, dramatically improve safety outcomes—not just for learners overseen by certain educators, or at a certain school, or for water-based activities, but across all schools and all learners throughout the entire 16 million person province.

However: getting a governmental agency to agree to regulate an industry that it may know little about, and has limited funding to address, is not always an easy feat.

And crafting high-quality regulations that skillfully balance sufficient detail with avoiding overburdensome and over-prescriptive requirements requires expertise and skill.

And finally, effectively enforcing regulations must be done, if the regulations are to be effective.

Recommendation 6: Strengthen public school safety regulations regarding learner supervision and water safety

Investigators recommended that the Regulations for Safety Measures at Public Schools of 2006 be amended to ensure there are more prescriptive controls regarding learner supervision and water safety procedures.

These regulatory changes, were they to be effected, could also broadly improve safety outcomes across all Gauteng’s public schools, subject to the caveats described in Recommendation 5 above.

The current regulations, associated with the South African Schools Act (No. 84 of 1996), and most recently amended in 2006, require schools to:

- Carry insurance, “depending on the availability of funds”

- Maintain educator-learner ratios of at least 1:20 or 1:30

- Manage learner medications

- Inform parents of school activities, including transportation, accommodation and itinerary details

- Submit incident reports

- Inform learners about dangers and safety measures regarding water activities in pools, rivers, or the ocean

- Supervise learners during all water sports

(The original regulations in 1996, which, like the current regulations, focus heavily on addressing violence in schools, and did not have these requirements.)

These regulations are admirable, and an upgrade from the 1996 version. They do not, however, contain sufficient detail to reduce risks of water-based or other outdoor activities as far as is reasonably practicable.

Safety measures: outdoor education group using helmets while scrambling. Credit: Gery Lovasz

Other Actions

In addition to a forensic investigation being made, several other events occurred following the incident.

GDE institutes procedural changes

The Department of Education reportedly directed schools to not use the provider near Brits, and to ensure all water-related activities included the presence of life jackets as well as lifeguards on site. All water-related activities would need approval by the GDE’s head office, not district offices.

The Department reportedly promised that consent forms would be amended to state that schools had visited any venue to be used, and “found it to be safe.”

GDE warns of “culture of silence” at school

In the days after Enock’s drowning, the Department of Education reportedly said it was concerned about an ongoing “culture of silence” at Parktown.

The 2018 report commissioned by the Department on the sexual abuse scandal at the school described a culture of silence surrounding practices including “sexually predatory behavior” and “a culture of assault and sexual assault under the guise of initiation practices,” it was reported.

Following the scandal, the school’s code of conduct was changed to give learners the freedom to speak up.

But after Enock’s death, news reports suggested an unwillingness on the part of the school to permit learners to express their views. “The principal told him that he mustn’t speak to anyone,” a parent of one of the learners at camp was reported as saying.

The Education Department noted the discrepancy between the new written policy and the historic culture of silence. The GDE was reported as saying that this “simply means we changed it on paper, but the culture continued.”

Venue renamed

Just as the Sir Edmund Hillary Outdoor Pursuits Centre changed its name to Hillary Outdoors following drownings on a school trip in 2008, the venue where Enock—and four others—drowned changed its name. The facility is now Beestekraal Events & Accommodation. Water activities appear to continue to be offered.

The venue, with original signage. Credits: eTV, EWN

Analysis

Following the drowning, the provider near Brits said that Enock’s death “should be considered an unfortunate accident, for which no one was to blame.”

We know this not to be true.

An investigation found individual negligence. And larger-scale missed opportunities also played a role in this tragic and preventable death.

Let’s now consider some ideas about understanding the causes of the tragic drowning incident, and approaches to developing the conditions to minimize the likelihood and severity of potential future incidents.

It’s a wonderful thing that public school students in South Africa get to experience the benefits of outdoor adventure education, team-building activities, and experiential education. Many students around the world—even in high-income countries—don’t have this opportunity.

But offering these experiences brings with it the responsibility to manage the risks of these activities appropriately. In Enock’s case and others, this clearly did not occur.

Considering Causation from a Systems Thinking Perspective

Why do incidents occur? Safety theoreticians have come up with a variety of models</u>; leading contemporary models incorporate ideas around how complex sociotechnical systems behave.

AcciMap and its variants recognize that safety outcomes can be influenced on a variety of safety levels: government, industry associations, businesses and their management, line staff, and the design of work processes.

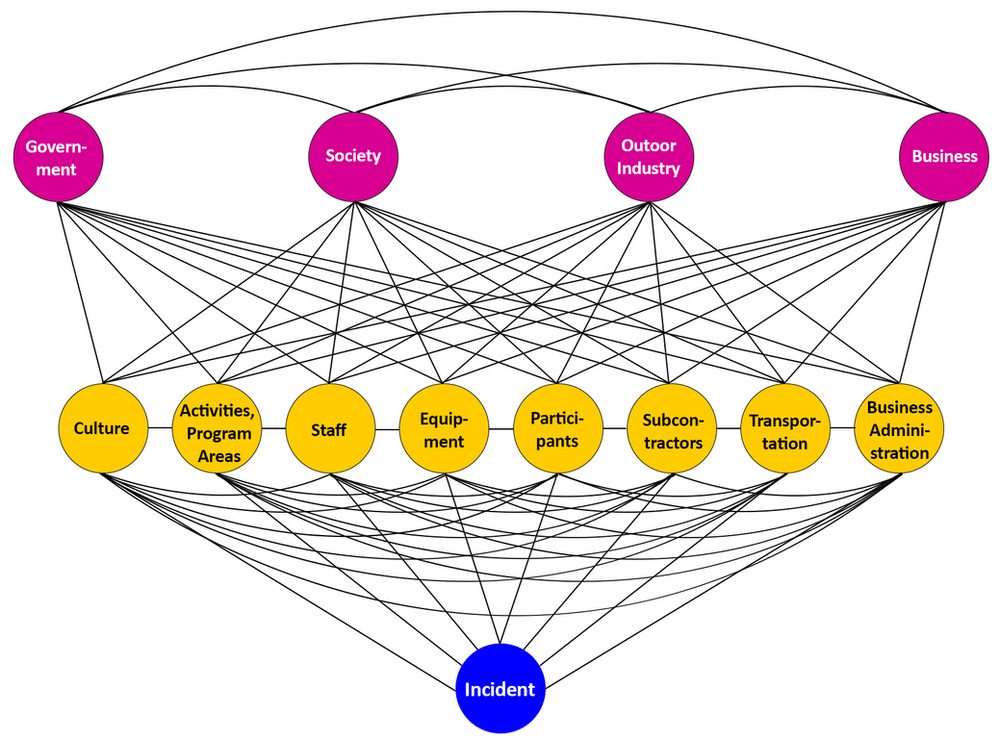

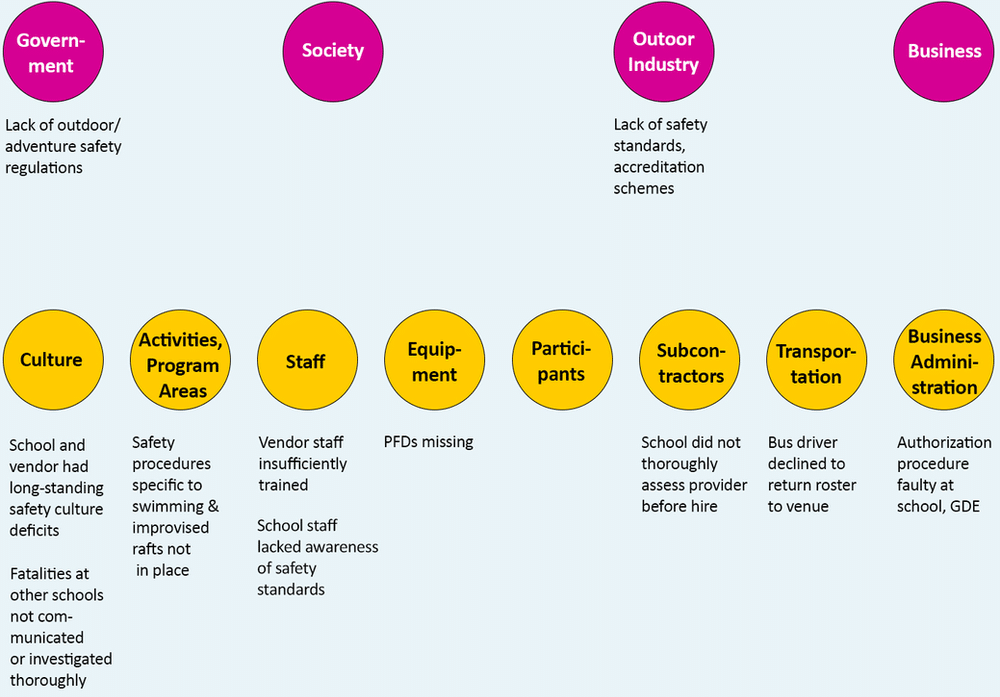

Another model designed specifically for the outdoor industry looks at a variety of ‘risk domains,’ where risks reside. The Risk Domains model involves identifying and managing discrete risks that may be present in any risk domain.

The eight direct risk domains, in yellow, indicate areas such as safety culture, risks inherent to certain activities, equipment management, and so on.

Underlying risks can indirectly influence safety outcomes. For example, government can set safety regulations. Societal risk tolerance influences incident response. The outdoor industry can set and maintain safety standards, and big corporations can support sensible safety regulation.

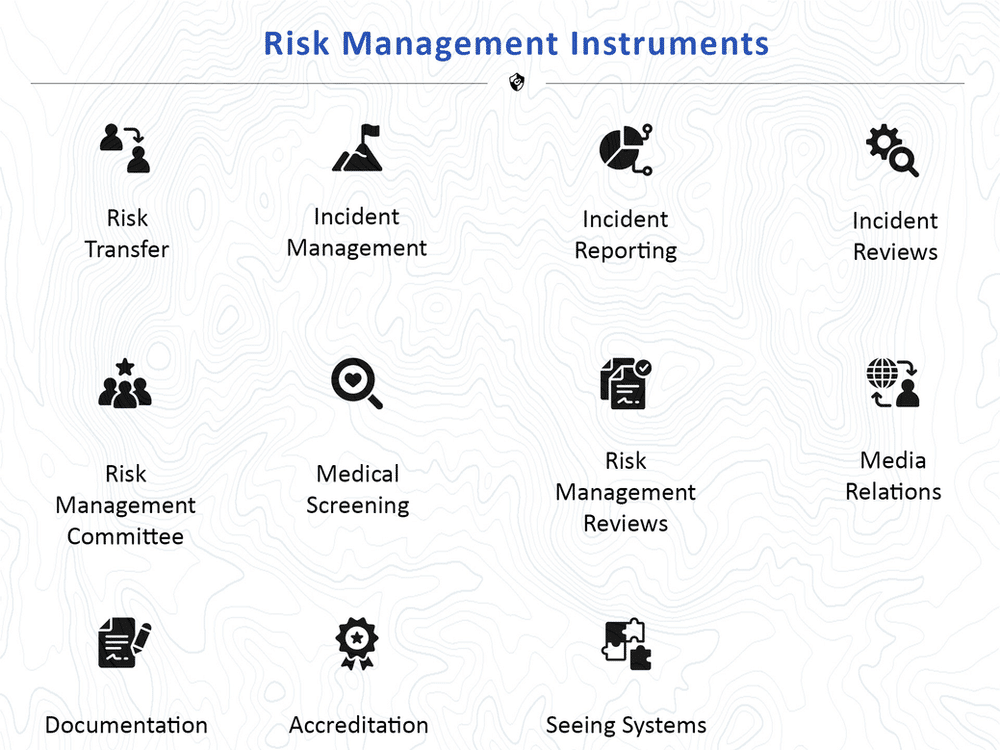

The Risk Domains model also involves using broad tools, or risk management instruments, to address risks across multiple or all risk domains at one time:

Risk Transfer refers to insurance coverage, subcontractor use, and liability waivers. Incident Management refers to emergency response plans. Incident Reporting means documenting safety issues and making changes accordingly. Incident Reviews means formally analyzing significant mishaps. Risk Management Committee indicates a group that provides outside perspectives and guidance. Medical Screening refers to evaluating staff and participant suitability for participation. Risk Management Reviews are periodic, proactive safety audits. Media Relations refers to being able to work effectively with news media. Documentation refers to recorded procedural information and records of action taken. Accreditation refers to recognition by relevant accrediting bodies, if applicable. Seeing Systems refers to using systems theory to help prevent and mitigate incidents.

Not all of these risk management instruments must be used by all program providers, but for many outdoor organizations, using at least most of them is appropriate.

No model is perfect. But any well-developed model can be useful in helping understand the causes of mishaps, and helping prevent or mitigate future incidents.

We can map certain opportunities for improvement regarding the incident at Nyati onto the illustration of risk domains:

We can also see that the provider did not employ most of the risk management instruments. There was no apparent emergency response plan, system for recording and learning from incidents, formal incident review procedure, risk management committee, medical screening process, proactive safety audit system, comprehensive set of documented safety procedures or records of actions taken, or systems-based approach to safety. However, the vendor did employ a media relations strategy, and there was no obvious accreditation system in place for them to fall under.

Examples of Systems-Informed Response

One example of a thoughtful and comprehensive response to an outdoor incident comes from Australia, where a 17 year old died after falling 10 meters from a “Rip Swing” ropes course element onto his head.

The investigation cited a number of causal factors from across the direct and indirect risk domains, including:

- Equipment: improper carabiner use

- Equipment: lack of required fail-safe systems

- Staff/Participant: participant improperly positioned (upside down)

- Government: health and safety agency inspected facility and failed to identify unsafe swing operation

- Government: deficient safety legislation (swing fell into unregulated loophole)

- Government: no inspection or certification of adventure facilities

- Outdoor industry: local camping association failed to comment on lack of fail-safe; voluntary system lacked authority to make changes

Inverted on a ropes course. Credit: NorthShore Zipline

In another Australian incident, in 2006 three teenage boys went hiking through summertime heat in Blue Mountains National Park. The creek where they expected to find water was dry. One boy ran ahead to find water, but veered off the trail. Seventeen hours elapsed from when he last had water. From deep in the bush, dying of thirst, he called the national emergency number from his phone—seven times—but dispatchers kept asking for his street address. His body was found eight days later.

The investigation recommended changes to emergency services operations, improvements to the safety procedures of the organization coordinating the trip, and a review by the Minister for Environment and Climate Change regarding how the climate crisis requires changes to information about safe water consumption.

Opportunities to Further Employ Systems Thinking

Systems thinking informs us that major incidents are often caused by a combination of factors from multiple risk domains that combine in unpredictable ways. We can recognize that our safety systems are likely to at some point break down—but how, and when, we can’t know in advance.

Therefore, we have to build in extra capacity, redundancy, and other elements of a resilient system, so that when there is equipment failure, or a person doesn’t follow procedures, or severe weather occurs, the overall safety system can withstand that breakdown without leading to a catastrophic incident.

This means that targeted safety interventions may have limited effectiveness, unless a comprehensive approach to safety is also applied.

For example, the GDE’s requirement that all water-related activities include the presence of PFDs may help prevent future drownings—but won’t stop a lightning strike, heat stroke, medication overdose, or any other incident not involving water-based activities. When we think creatively about potential future incidents, the need for broadly effective measures becomes clear.

The GDE decided to introduce a “risk classification tool” to identify risks. This is an important and useful tool for addressing discrete risks—like drowning, in the absence of PFDs and trained facilitators. But as major incidents frequently come about from combinations of risks that cannot be anticipated in advance, simple probabilistic risk assessments should be combined with systems-informed approaches to be most effective.

As a final example: the requirement that schools visit any venue to be use and “find it to be safe” will be most useful when it comes with:

- Detailed and well-developed standards for evaluating venue safety

- Training for providers on how to meet those standards

- Training for school-based assessors regarding how to evaluate venues to those standards

- Funding to support standards development and training

Further information on systems-based approaches to outdoor safety is available in the text Risk Management for Outdoor Programs: A Guide to Safety in Outdoor Education, Recreation and Adventure.

In addition, a 40-hour training course, Risk Management for Outdoor Programs, offers outdoor professionals an opportunity to more deeply explore the topic.

Improvised raft with abundant PFD use. Credit: Taiwan Discovery

Solutions

Resolving the issues brought to prominence by the Crocodile River incident requires interventions at multiple levels in the complex socio-technical system that is the outdoor activity sector in South Africa.

We’ll look here at two areas—or ‘indirect risk domains’—that can have a significant impact on safety outcomes for the outdoor industry in southern Africa.

One is government, specifically with regards to regulation, funding, and training.

The second is outdoor industry bodies, and their role in setting and enforcing standards.

The role of government regulation

Governments have the power to create regulations with which it is compulsory to comply.

These regulations differ from two other forms of regulation—self-regulation, for example when an outdoor program decides on its own to meet high safety standards, and third-party regulation, such as provided by an industry association setting standards and providing accreditation to those who meet them.

All three types of regulation have a role to play in influencing safety (or other) outcomes. However, government regulations tend to be the most influential, as conformance is obligatory, and there are penalties for those who do not follow them.

Government regulations are also perhaps the most difficult of the three to institute. This can be because crafting regulations in an inclusive and deliberative manner that balances the needs of all stakeholders is inherently challenging, and due to the fact that many governments face pressure to reduce tax-funded expense and regulatory burdens.

A word on terminology: government regulation, often crafted by a government’s executive branch, can be contrasted with legislation, typically written by a government’s legislative branch. Legislation is often broad and general in scope. Regulation fills in the details. Standards and detailed written guidance add even more definition to what’s described in regulations.

For example, New Zealand’s workplace health and safety law is the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, addressing broad topics like duty of care and safety committees.

Under that are the Health and Safety at Work (Adventure Activities) Regulations 2016, which specifically describe how adventure activity operators are required to pass safety audits, and how auditors are managed. The regulations also require the development of safety audit standards for adventure activities, which go into detail regarding staff training, equipment management, field communications, and other outdoor safety specifics.

Outdoor safety regulations: an international comparison

The report commissioned by the GDE recommended strengthening the Regulations for Safety Measures at Public Schools of 2006. These regulations offer highly general guidance, such as informing learners about safety measures, and supervising learners during water activities. But they don’t provide specific guidance, such as qualifications of supervising adults or staff-to-participant ratios, that can help ensure a high level of risk management.

Let’s take a look at outdoor safety regulations elsewhere, to see what strengthened safety measures for outdoor activities might look like.

Since the incident at Nyati was water-based, involving swimming and improvised rafts, we’ll start by reviewing safety regulations that cover those activities.

United Kingdom

After four students died on a 1993 kayaking trip in Lyme Bay on the south coast of England, the United Kingdom passed the Activity Centres (Young Persons’ Safety) Act 1995 and, the following year, Adventure Activities Licensing Regulations.

Lyme Bay on a calm day

The regulations cover improvised rafts and fast-flowing inland waters. They require “sufficient numbers of competent instructors.” Adventure providers must pass an inspection by a qualified auditor before a license to provide adventure activities will be granted.

New Zealand

New Zealand’s Adventure Activities regulations go into even greater detail.

The regulations require the government to develop safety audit standards, which cover water-based activities. A 52-page manual on “Requirements for bodies certifying adventure activity operators’ safety management systems” covers, in great detail, the accreditation of organizations that provide auditors that evaluate adventure activity providers.

The standards, although not covering water-based activities specifically, outline requirements to support good risk management of all kinds of adventure activities. These include that adventure activity operators:

- Pass a third-party safety audit by an accredited auditor before providing activities

- Have a written and up-to-date Safety Management System (SMS) informed by activity-specific safety best practices

- Ensure staff comply with the SMS

- Develop Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for each activity, in conformance with good practice, including staff-to-participant ratios and staff positioning

- Ensure staff are competent

- Ensure equipment is available in sufficient quantities

- Maintain an emergency response plan, incident reporting procedure, and incident review process

- Conduct regular internal reviews

Singapore

Singapore takes outdoor activities seriously, and takes safety seriously. As a result, the country has some of the most well-developed outdoor risk management systems anywhere. School-based water activities are no exception.

Singapore’s Ministry of Education publishes a 101-page Outdoor Adventure Learning Activity Guide for MOE Schools, which includes an eight-page chapter exclusively devoted to improvised rafting.

Improvised rafting in the South China Sea. Credit: Mariya Georgieva

The government agency’s requirements for improvised rafts include:

- Instructor must provide evidence of competency, and must demonstrate hitches, lashings, and raft manoeuvring skills

- 1:10 instructor to student ratio

- In addition to an instructor for every 10 students, a safety supervisor is required, who keeps all students in sight at all times, and sounds an alert immediately if any student requires assistance

- PFDs are required to be worn

- Safety briefings must be given to students before the activity

- Instructors must conduct a water confidence test in shallow waters prior to the first launch of the improvised raft

Numerous other requirements and details are also included.

One can imagine that if South Africa’s GDE had guidance in place anywhere remotely similar to the Singapore MOE’s requirements, it would have been inconceivable that the improvised rafting activity on the Crocodile River would have unfolded in the way it did.

The MOE’s guide also addresses walking, kayaking, white-water rafting, climbing, abseiling, challenge course and overnight camping.

In addition, the MOE also lists safety criteria in its Compliance Checklists for Procurement of OAL Activities.

On top of all that, Singapore is now working on a large-scale, multi-year effort to develop a national safety and quality standard for outdoor adventure education.

Outdoor safety regulations: resource constraints

The development and implementation of comprehensive outdoor safety regulations faces the challenge of limited resources available to invest in this effort.

Limitations arise from economic circumstances, population size, and competing safety priorities.

Financial resources and economic priorities

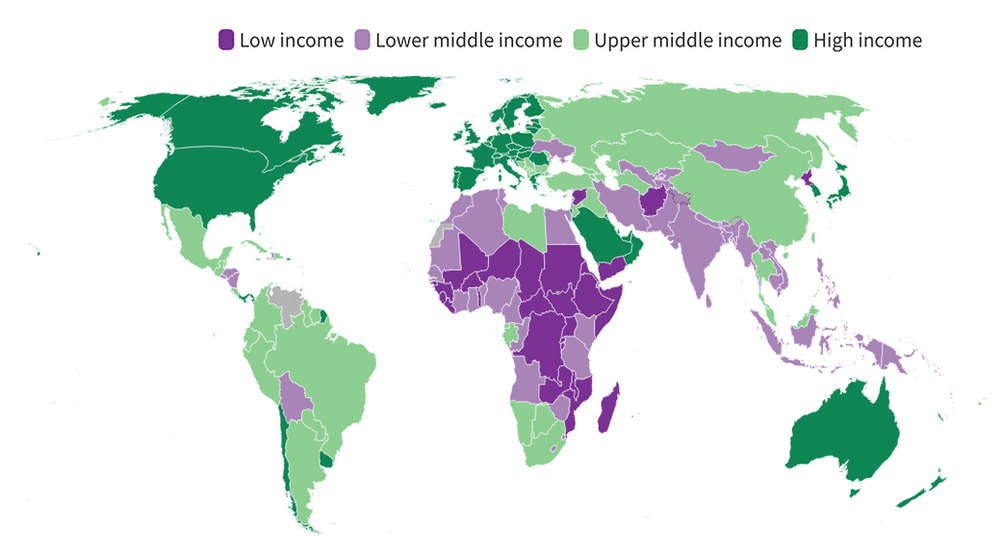

South Africa is not a high-income country, like the UK, Singapore, or New Zealand. Consequently, all players—government agencies, schools, and outdoor program providers—have limited capacity to invest in creating, implementing, and conforming to new regulatory requirements.

Over-burdensome regulations can have a significant impact on outdoor program providers. For instance, when the UK’s Adventure Activities regulations were introduced, even though they were thoughtfully developed and not excessively onerous, many outdoor activity providers went out of business. (The sector has since rebounded.)

Similarly, the increased costs of complying with the adventure activities regulations and safety audit standard in New Zealand put significant financial pressure on the sector. Ongoing financial support from the government has helped ameliorate this.

A major outdoor education provider in Singapore began building a new USD $185 million outdoor adventure education campus, complete with artificial abseiling waterfall, in recent years, and at the same time kept a staff of over 100 on the payroll for years throughout the COVID-19 pandemic even though the organization had no participants due to COVID-19 restrictions. For the vast majority of outdoor programs (in South Africa or anywhere), this isn’t a realistic option.

Any regulations imposed on the South African adventure activity sector should be developed with industry input and crafted to establish high safety standards without making the provision of organized outdoor activities financially unsustainable.

Global income by country. Credit: World Bank

South Africa also prioritizes economic development in its government policies. Supporting businesses to be financially successful, helping entrepreneurs succeed, providing employment opportunities for those without extensive academic qualifications, and creating pathways to reduce poverty are key national aims.

Regulations, then, must not make it unreasonably harder for people to start or maintain outdoor businesses.

Smaller-country constraints

The USA, with a population of some 330 million, has a relatively large number of universities generating thought leadership and highly-trained outdoor professionals, and a variety of industry associations that advance the outdoor education and outdoor recreation fields.

South Africa, with a population of some 60 million, simply doesn’t have the people resources to have a robust industry association for every type of outdoor activity, and which can come up with accreditation schemes and consensus standards for all manner of outdoor pursuits.

This issue is also reflected in eastern Europe, where the death of a Serbian mountaineer while climbing in the Albanian Alps may go without skilled investigation due to lack of a suitable government body (or mountaineering association) to do so.

Očnjak, or ‘Canine Tooth,’ in the Albanian Alps, where the Serbian mountaineer fell. Credit: SummitPost

However, outdoor adventure is a substantial part of South Africa’s culture and economy, and the country has an impressive array of outdoor associations, ranging from groups covering paddling and ropes courses to parachuting, kiteboarding, kitesurfing, and surfing, among others.

Hard choices about safety priorities

Safety is undeniably a priority for Gauteng schools. But schools face myriad, complex safety concerns.

Enock’s death was not the only fatality to befall a school pupil in Gauteng. The same day of Enock’s death by drowning, another Gauteng student drowned in a school swimming pool.

In just the first eight weeks of the year, the Gauteng school community dealt with 18 deaths. One student was fatally struck by lightning while walking home with fellow pupils. Another student was found in the bushes, reportedly having been raped, stabbed and burnt to death. In two separate incidents, two students died after drinking poison. Another died after jumping from a moving minibus after passengers allegedly assaulted her. Two pupils died in separate incidents after allegedly being stabbed by other students. One was swept away in a flash flood while crossing a makeshift wooden bridge over a stream; another fell from the third floor of a school. Several were killed in motor vehicle accidents.

This is horrific by any measure. Effectively addressing the underlying causes of these incidents—which go far beyond risks encountered in outdoor education programs—can strain the resources of any provincial education department or government.

Two examples—one in Singapore, one in the USA—illustrate differences in responses to school-based safety incidents.

In February 2021, a school learner died on a high ropes course at a school-sponsored event in Singapore. In response, the Singaporean government halted all high elements activities for all schools across the entire country. As of August 2022, the nation-wide prohibition continues to be in place, with a targeted re-opening of some time in 2023.

A 15-year old learner from a school in Connecticut, USA contracted tick-borne encephalitis on a school trip to China. An extensive, multi-year analysis and legal process followed, ending with a jury requiring the school to pay USD $41,500,000 to the student.

Panshan, Tianjin, China, where the encephalitis incident occurred

Loopholes

Safety regulations aren’t effective if they don’t cover a certain activity, population or sector. Many outdoor safety regulations exempt schools from their requirements, even though the activities and risks may be identical.

New Zealand outdoor safety regulations are an example. In 2008, Emily Jordan, a 21-year old British law graduate, drowned in a riverboarding accident in New Zealand, when she became trapped underwater for 20 minutes in the Kawarau River. Emily’s father pushed the New Zealand government to create safety regulations, which they did. But the regulations cover recreational outdoor adventures for tourists, and school programs are exempt.

This is the case, even though Emily’s drowning occurred just two weeks after the death of six learners and their teacher in a flooded river in the country’s Tongariro National Park.

Emily Jordan. Credit: Guardian/PA

Similarly, the adventure safety regulations established in the UK following the deaths of four students on the kayaking trip in Lyme Bay exempted schools from following their requirements.

Outdoor safety regulations in India also exempt schools.

And outdoor adventure regulations in Switzerland only apply to activities “offered on a professional basis,” and exempt nonprofit clubs and associations.

Regulations not a panacea

Well-developed government regulations are a powerful tool to drive improvements in outdoor safety. This is especially the case when they are thoughtfully written with outdoor industry input, come with funding for training and implementation by industry providers, are appropriately enforced, and are continually reviewed for updates and improvements.

However, no regulation can prevent all incidents, or even all tragedies.

New Zealand’s outdoor safety regulations are among the world’s best. And yet, following their issuance, the 2019 eruption of Whakaari/White Island killed 22 people who were exploring the island. The incident called into question the effectiveness of the country’s regulations and how they were enforced.

Outdoor adventure deaths also occurred in New Zealand involving climbing, quad biking, buggy touring and diving.

One of the stress points identified in the investigations following the Whakaari/White Island incident was the health of the third-party audit system, including the difficulty in retaining qualified auditors.

Whakaari/White Island, before and during the explosion

The issue of third-party auditors also arises in accreditation systems relying on a peer evaluation process, where staff from one provider perform site visits of another provider during the accreditation review process.

Particularly in smaller industry circles, where providers may depend on each other to borrow staff or other resources from time to time, individuals may feel pressure to provide passing marks during audits even if deficiencies are noted, so as to maintain professional relationships.

Auditing systems that take steps to insulate site visitors from these pressures will help ensure the integrity of the accreditation inspection process.

The role of government funding and training support

Government entities seeking to create an environment that sustainably supports improvements in outdoor safety often combine regulation—the ‘stick’—with multi-year funding and support for provider training—the ‘carrots.’

Australia

For example, the Australian government fully funds Outdoor Leadership certificate courses through the Technical And Further Education (TAFE) vocational training scheme. Students can complete 400-hour Certificate IV in Outdoor Leadership over 18 weeks, normally AUD $13,000 or more, for completely free or a nominal cost.

A 12-month Diploma of Outdoor Leadership is also offered through the TAFE system, with generous government subsidies covering most costs. Both courses provide extensive risk management training.

The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning in the Australian state of Victoria provided seed funding to develop an Adventure Activity Standard providing detailed outdoor safety guidance, and ten Offices of Recreation and Sport from states and territories across the country later pitched in to support nationwide outdoor safety standards.

New Zealand

Similarly, WorkSafe NZ and Sport New Zealand provided funding to outdoor program providers to help them understand and implement the country’s Adventure Activities Regulations. They also provided funding to establish detailed and high-quality training resources to provide ongoing support to the sector.

Costa Rica

When Costa Rica abolished its military, it invested the money from former military budgets into education. Costa Rica created the National Learning Institute, or INA, which provides free training for Costa Ricans in a variety of subjects, including in outdoor recreation and education.

INA’s one-year, 1,000-hour guide certification training focusing on outdoor adventure tourism includes training in whitewater rafting, kayak rescue, and bungee jumping, along with a 132-hour first aid course.

INA-certified guides and others completing safety training in Costa Rica

India

When the state of Maharashtra in India issued outdoor adventure regulations in 2021, the Government Resolution also required the state to provide a training center for adventure tourism; equipment, training and financial assistance for outdoor rescues, and a state-level committee to promote adventure tourism.

South Africa may not be able to marshal the resources to provide free year-long outdoor education training courses for outdoor educators and facilitators. Yet government investment in supporting funding and training opportunities for outdoor leaders has a clear precedent around the world, and can support safety and quality of outdoor programs, and the human development and economic benefits those programs can bring.

South Africa: Training for Adventure Tourism

South Africa does have a relatively well-developed training system for outdoor adventure tourism, although it doesn’t apply to outdoor adventure school camps or other school programs.

In South Africa, tourism guides—including adventure, nature and culture guides—must have a government-issued certificate of competency. Outdoor adventure guides must go through training and pass an assessment procedure by a government-accredited Assessor.

Certificates have been historically issued by the Culture, Arts, Tourism, Hospitality and Sport Sector Education Training Authority (CATHSSETA), who also accredits training providers and assessors. The Quality Council for Trades and Occupations (QCTO) will be the responsible entity starting in the near future.

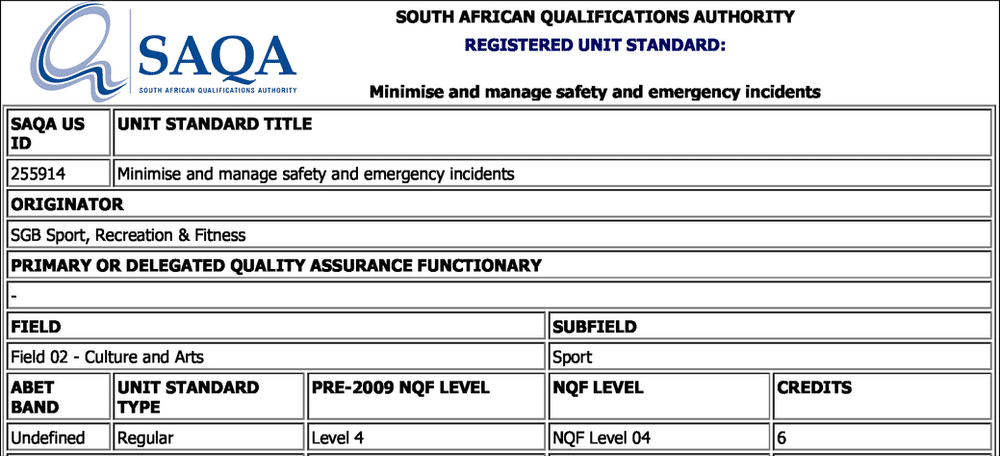

SAQA Unit Standard 255914, Minimise and manage safety and emergency incidents

Training units are specified in the National Qualifications Framework managed by the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA).

One unit standard in the Tourist Guiding qualification is 255914, “Minimise and manage safety and emergency incidents.” Learners completing this standard are able to implement incident prevention policy, and manage incidents which affect an individual or group.

This unit standard is also used in the SAQA Qualification 66190, Adventure Based Learning National Certificate, the development of which used Australia’s TAFE Certificate IV in Outdoor Recreation as a reference.

The role of industry bodies

Government agencies have the power to regulate, but they often don’t know the industry as well as do career professionals in the field. Industry associations can provide detailed standards and qualifications structures that help make broad regulatory requirements more useful on a practical level.

Many industry associations around the world have developed detailed best practices, and accreditation or certification schemes to help organizations and individuals conform to those practices.

These best practices cover everything from assessing providers (subcontractors) before hire to ensuring that participant rosters are sent to the provider weeks in advance, with participants divided into groups, and then provided to individual facilitators, who carry the rosters with them at all times.

Multi-Activity Associations

The Association for Experiential Education has developed an accreditation system that sets the gold standard for experiential adventure programs.

The Outdoor Learning and Adventure Education Association has also developed detailed outdoor safety standards.

The American Camp Association’s accreditation system uses a 208-page Accreditation Process Guide containing exquisitely detailed guidance on safety and quality, and which is used by thousands of summer and year-round camps. ACA’s accreditation standards for water-based activities, for instance, include criteria regarding lifeguard certification, aquatics supervisor qualifications, lifeguard positioning for observation and intervention, location-specific swim area rescue skills, aquatic supervision ratios, aquatic lookout training, written aquatic safety regulations, aquatic-specific emergency procedures, swimmer accounting systems, swim testing, aquatic equipment management, aquatic hazard management, aquatic site boundary establishment, and PFD use, in addition to general standards regarding risk management plans, safety briefings, missing person procedures, screening procedures, emergency response, and emergency plan rehearsal.

A broad coalition of state and national outdoor bodies across Australia came together to craft the Australian Adventure Activity Standard and associated Good Practice Guides. The voluntary standard crafted by these associations may be incorporated into accreditation criteria, and, eventually, Australian legislation may be passed to mandate conformance to the standard.

The Maha Adventure Council helped develop a 267-page set of voluntary good practice standards for outdoor activities to complement the 16-page Government Resolution passed by the Government of Maharashtra on adventure tourism safety.

Tourism bodies around the world, such as Ferðamálastofa (Icelandic Tourist Board), the Australian Tourism Industry Council, the Adventure Travel Trade Association, and the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India have all put together standards addressing outdoor adventure safety and quality, to varying levels of thoroughness and rigor.

Ferðamálastofa’s ‘Vakinn’ safety and quality system regulates outdoor adventures in Iceland. Credit: Gabriel Côté-Valiquette

South Africa’s set of adventure associations also provide guidance for their members. Two notable organizations focused on a wide range of outdoor and adventure activities are SATSA and SA AIA.

The Southern Africa Tourism Services Association (SATSA), a nonprofit association representing private sector tourism, is developing a voluntary self-accreditation process for adventure tourism operators covering the full spectrum of adventure activities. Overall and activity-specific safety and operational standards will be published, and site visits may be used to evaluate standards conformance.

The South African Adventure Industry Association (SA AIA) is the umbrella body for the Southern Africa outdoor and adventure industry. SA AIA, established in 2020, seeks to advance professionalism, safety, and inclusion in the adventure industry. The Association is working to create voluntary regulations and guidance which can support school camps, adventure tourism operations, and all other forms of outdoor adventure in southern Africa.

SA AIA seeks to provide support for individual adventure guides, operators and businesses, government agencies, and activity-specific associations. The organization aims to support job opportunities and economic development for young South African entrepreneurs.

Activity-Specific Bodies

Myriad activity-specific associations, peak bodies, or governing bodies exist for nearly all manner of outdoor activities. A sample follows:

The International Federation of Mountain Guide Associations (UIAGM/IFMGA) determines training standards used by its member associations (none of which are in Africa).

The Association for Challenge Course Technology is a leading association setting standards and providing certification and accreditation in the challenge course, canopy tour, and zip line industry, covering everything from foefie slides to massive aerial adventure parks.

The UK Canyoning Association is one of several canyoneering associations, and provides standards and certification for kloofing and gorge walking.

Standards and certification in sea kayaking are addressed by various associations around the world, from British Canoeing to the American Canoe Association and the Singapore Canoe Federation, among others.

Others activity-specific bodies providing good practice standards, certification or accreditation abound, with some countries having relatively few, and others, such as the UK, containing multitudes.

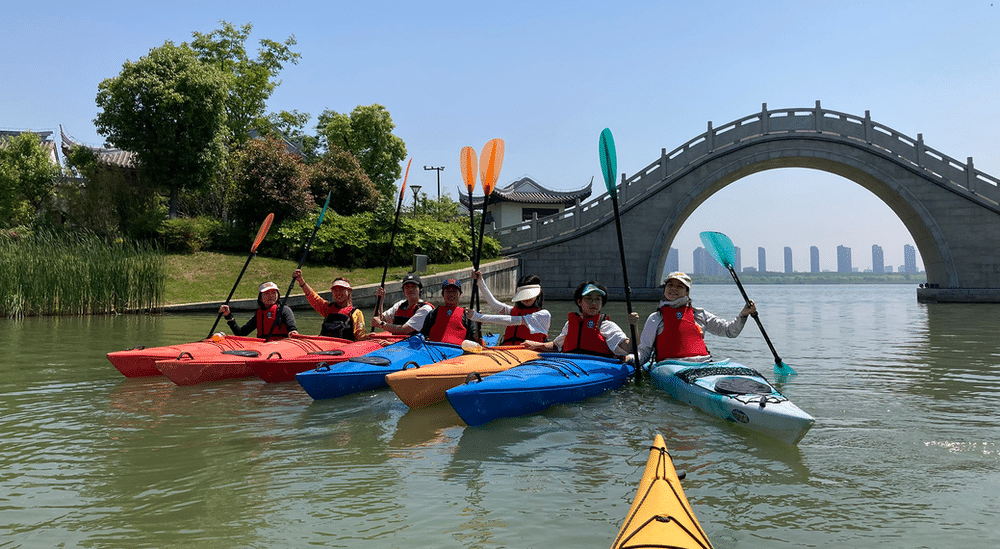

A school group going sea kayaking as part of an outdoor education program in China. Credit: Mariya Georgieva

Supporting systemic change

Industry associations, especially those that span the spectrum of activities that comprise the outdoor adventure sector, can be effective in significantly elevating the quality and safety of participants’ experiences.

When associations create high-quality accreditation schemes, comprehensive good practice guides, and rigorous practitioner certification systems, these can influence the complex socio-technical system of the outdoor adventure sector more fully than highly targeted interventions such as requiring PFD use—excellent for future water-based activities, but not effective for risks across the full set of activities and risk domains.

Organizational accreditation systems, qualification/certification schemes for individual practitioners, and good practice standards are most likely to be widely adopted when they are supported by sensible regulations and multi-year funding from government entities to encourage and enable their widespread use.

Conclusion

Enock Mpianzi, one of four children of Antoinette and Guy Intamba, was known as a humble and respectful person. His family described him as an intelligent child who would excel in tests and examinations.

The day before the camp began, Enock was so excited to attend, he was unable to sleep.

That Enock’s promising life was cut short, as he eagerly went to participate in outdoor adventures, trusting the adults around him to help keep him safe, is a terrible loss.

A path forward is clear. Thoughtful, systemic measures at the government, industry association, school and program provider level can create effective, durable changes in how outdoor adventures are organized and conducted.

Outdoor adventure programs have the potential to foster joy, life skills, environmental awareness, and increased well-being in participants. High-quality outdoor experiences can contribute to sustainable economic development and a vibrant civil society.

Outdoor adventures invite participants to overcome challenges, in order to encounter new experiences and discover previously unknown capacities.

Leaders in the outdoor education and recreation sector, too, can overcome obstacles to making advances in the profession, and find their efforts result in new heights of quality and safety in outdoor programs.

With diligent, thoughtful work, we can make the world of outdoor adventure safer and better.

Every adventurer, every child, will benefit.