Emily Jordan, 21, from had just graduated with first-class honors from her university law program.

She was known as a bright, fun-loving person who loved life.

In search of adventure, she traveled from her home in Worcestershire, England to New Zealand, for a gap year experience.

Fit, slender, and athletic, Emily was a keen scuba diver and a good swimmer, and she signed up for an April 2008 whitewater riverboarding excursion down New Zealand’s Kawarau River.

Emily became trapped underwater, against a large rock.

The guides leading the riverboard experience attempted to extricate her, but were unable to do so.

Eventually, a boat from another adventure provider passed by, and were able to provide a rescue rope to assist with the rescue. Guides from the other riverboarding company used the rescue rope and retrieved Emily’s body within minutes.

By that point, Emily had been underwater for 20 minutes, and she did not survive the incident.

Death by Misadventure

The owner of the riverboarding operator said his company had done nothing wrong, and that Emily’s death was not preventable. “There is nothing we could have done,” he said. “Accidents happen.”

But is that really the case?

The district court in Queenstown, New Zealand heard that the company’s safety plan fell short of national standards. The organization’s guides, the court heard, did not carry ropes, and Emily was trapped underwater until another boat carrying ropes arrived and freed her body.

The inquest investigation of Emily’s death found that:

- Information and instruction were not given to clients in a way that clearly represented the true risks of danger.

- Training received by the guides was inadequate for emergency rescue and entrapment.

- Guide training was not specific to the particular activity of riverboarding.

- Riverboarding is not regulated by an external body.

- Lack of essential lifesaving equipment at hand—such as a whistle, rope and knife—was a major factor in delaying the speed of rescue.

- The one-size-fits-all life jacket was clearly unsuitable for riverboarding with respect to buoyancy and lack of safety features, such as crotch strap, D-ring and whistle attachment.

- A rescue craft was not available.

The inquest jury’s foreperson stated, “We believe a combination of all these factors and events contributed to the death of Emily Jordan.”

The coroner overseeing the inquest agreed with the jury’s findings. He said, “There is the likelihood that Emily’s death could have been avoided.”

“The overall impression one gains on listening to the evidence is that the guides panicked; they did not know what to do, and they did not have the equipment with which to do it,” the coroner stated.

The jury returned a verdict: death by misadventure.

The Safety Role of the Hierarchy of Controls

A certain amount of risk is part of any adventure activity. And yet, there are well-established practices where the adventuresome nature of an activity can be maintained, while eliminating or minimizing certain risks.

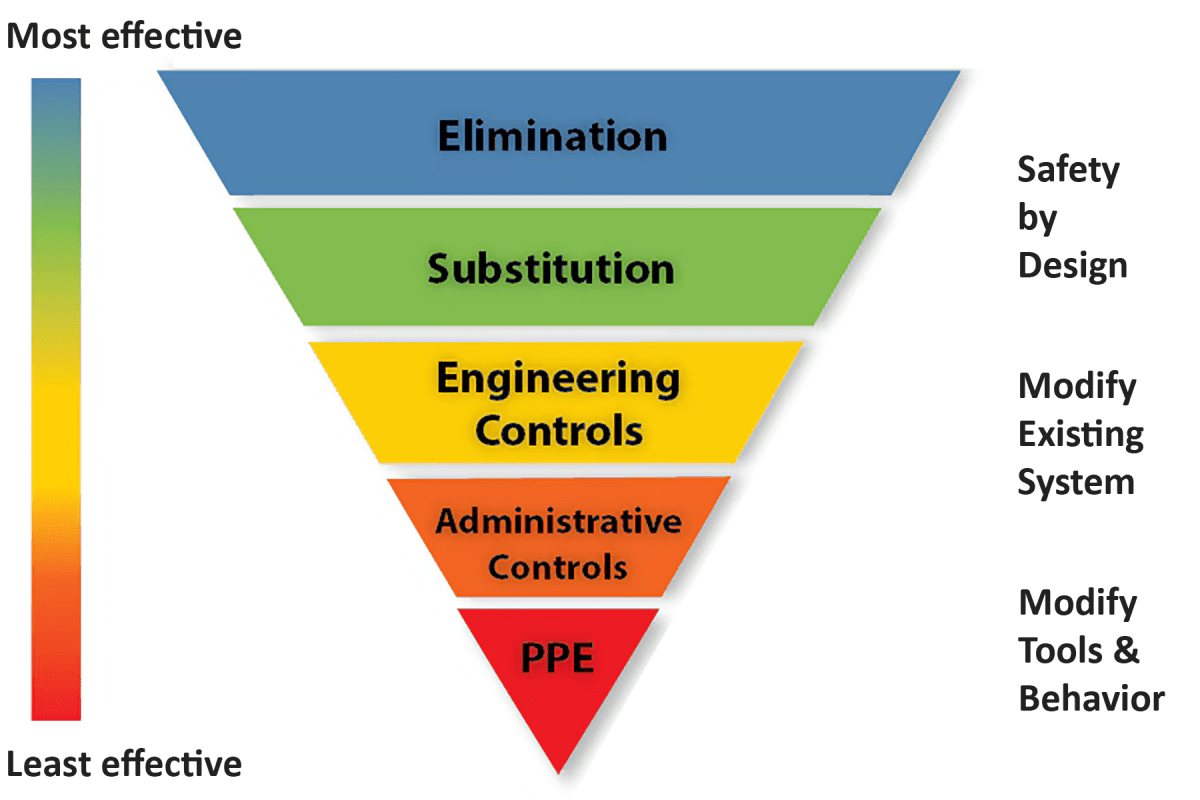

A classification of risk management measures, ordered from the most effective steps to the least effective, has been developed. This prioritized list is known as the “Hierarchy of Controls.”

The Hierarchy of Controls involves—in descending order of effectiveness—designing out risks in the first place, when establishing activities or processes; substituting lesser hazards in place of greater hazards; implementing engineering controls such as barrier devices to isolate people from hazards; implementing administrative controls such as training and safety procedures, and—last and least—using personal protective equipment.

Was the riverboarding operator aware of this hierarchy of controls? Did they take all reasonably practicable steps to implement all appropriate controls in the hierarchy, starting with the most effective measures?

If they did not: could having done so have prevented Emily Jordan’s death?

Regardless of how one answers these questions, it’s clear that outdoor, travel, and adventure operators can benefit from understanding and skillfully applying the Hierarchy of Controls to their programs and activities.

What is the Hierarchy of Controls?

The Hierarchy of Controls is a list of risk management measures a company can take, ordered from most effective to least effective. The Hierarchy of Controls (HoC) helps businesses effectively and efficiently reduce workplace risks.

The HoC also indicates the order in which risk management actions should be taken, when designing processes and products.

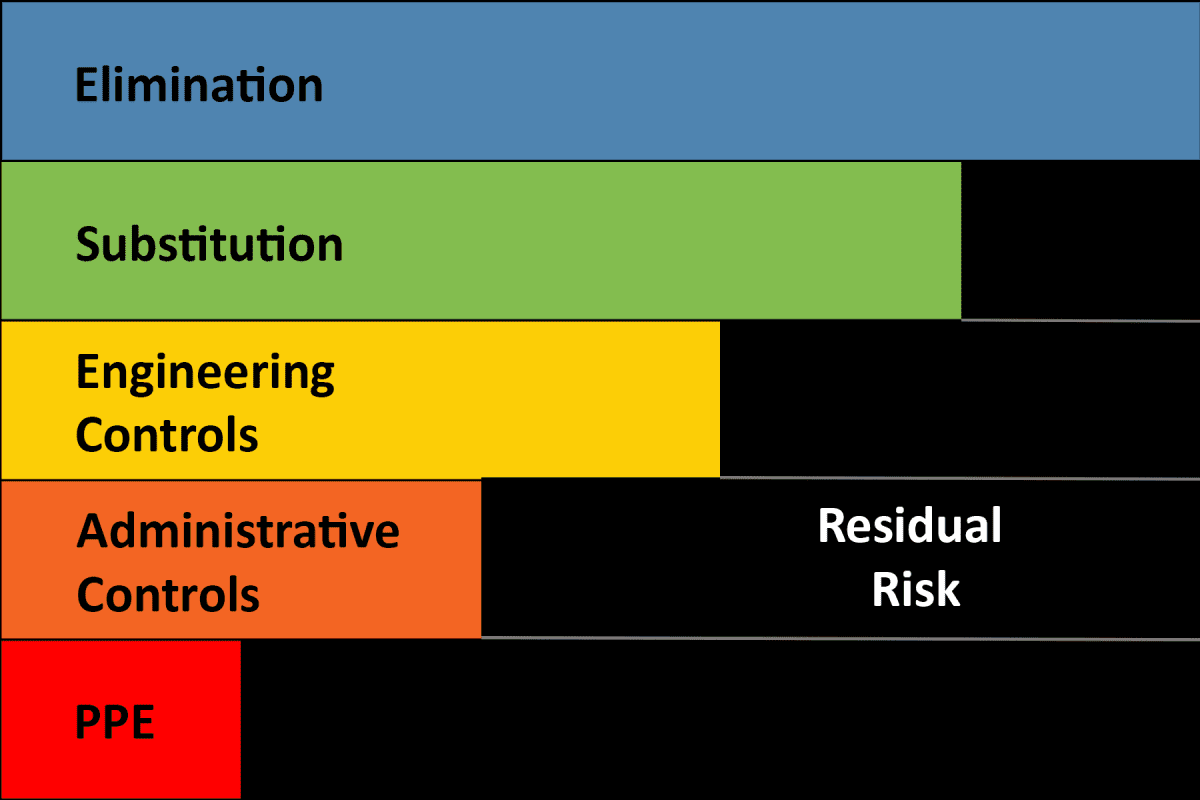

Control measures should be used in combination, in a layered approach, to reduce risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

Order of Actions: Top to Bottom

The Hierarchy of Controls specifies five different types of actions a company can take to reduce workplace risks. These are:

- Elimination: remove the hazard

- Substitution: replace the greater hazard with a lesser hazard

- Engineering controls: isolate people from the hazard

- Administrative controls: change the way people act

- PPE: protect people with personal protective equipment

The preferred order of actions for best control exposure to hazards is to first identify hazards, and then start at the top of the Hierarchy of Controls to address those hazards, and the risks that arise from interaction with those hazards.

Eliminate

Organizations should apply the Hierarchy of Controls beginning with the topmost control measure, Elimination. This means the organization should eliminate any hazards that are reasonably practicable to remove completely.

Because risks are designed out of the system and cannot cause harm, this is a highly effective control measure.

Using the top part of the Hierarchy of Controls is sometimes referred to as Safety by Design, or Prevention through Design—reducing risks by designing them out of the system in the first place.

Substitution and Engineering Controls

For any hazards that remain after the Elimination step, the organization should use substitution and engineering controls to:

- Replace a higher hazard with a lesser hazard

- Change the design or isolate people from the hazard

These steps elegantly reduce risk without requiring action on the part of workers or others. In this way, they are more effective than control measures that only work if people follow safety directions correctly.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is a body of the government of the USA under the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the Institute conducts research and makes recommendations regarding workplace health and safety. NIOSH notes, “Elimination, substitution, and engineering controls are more effective because they control exposures without significant human interaction.”

Administrative Controls

Administrative actions include training, the use of operating procedures, and warning indicators such as signage to minimize exposure to hazards.

However, people may or may not apply training guidance, follow operating procedures, or heed warnings.

Worksafe Victoria, the occupational health and safety regulator in the state of Victoria, Australia, reminds businesses that compared to elimination, substitution, and engineering controls, administrative controls have a “low level of protection and less reliable control.”

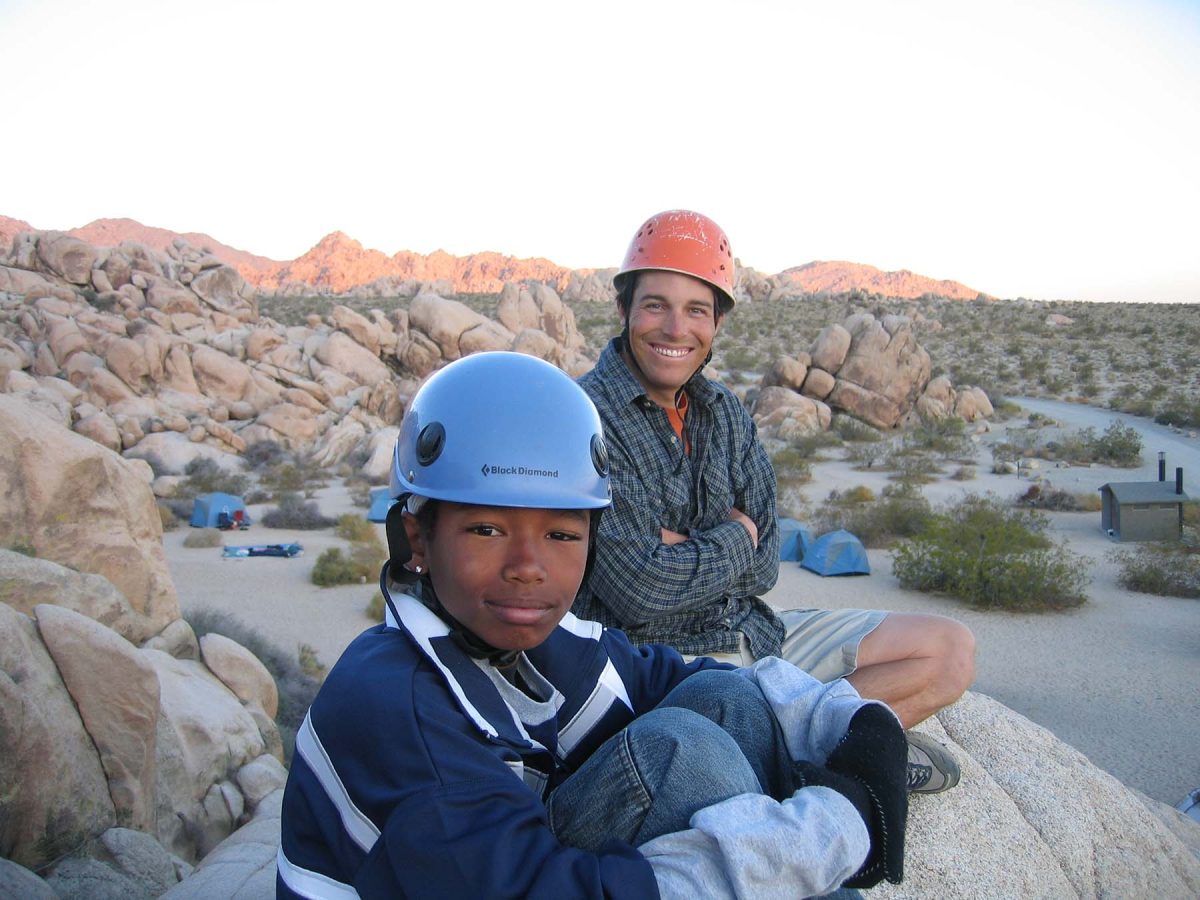

Personal Protective Equipment

Are any risks still remaining? If so, the operator should protect people with personal protective equipment.

This includes items such as helmets, gloves, boots, and protective clothing like warm jackets to guard against the cold, or broad-brimmed hats for protection from the sun.

This, Worksafe Victoria reminds us, has the “lowest level of protection, and least reliable control.”

Examples of Measures for Each Level of the Hierarchy

Following are examples of steps that outdoor, travel, experiential and adventure-based organizations can take to reduce risks at the five levels of the Hierarchy of Controls.

Remove the hazard

- Design trekking program itinerary to remove driving at night, when people are tired and visibility is reduced

- For international travel program, remove countries from destination list when government-issued travel advisories are at “do not travel” level

- Prohibit use of camp stoves in tents to eliminate asphyxiation risk

- Allow dogsledding expedition participants to create quinzhees (snow shelters) but do not allow sleeping inside them, to eliminate suffocation risk

- Paddle on rivers rated only Class III or lower

Replace the hazard

- When organizing international travel, give preference to airlines who have passed the IATA Operational Safety Audit (IOSA) and are listed on the IOSA registry of the International Air Transport Association (IATA)

- Adjust mountain travel itinerary to avoid slopes with moderate to high avalanche risk

- For a personal growth-focused wilderness expedition, choose backpacking over technical mountaineering

Isolate people from the hazard

Keep prescription medication and flammables such as stove fuel locked up at basecamp and away from youth participants on an excursion, unless youth are directly supervised

Require individuals who are not actively cooking to stay away from the camp kitchen, especially stoves, fires and knives

Change the way people act

- Incorporate measures such as training, SOPs, required rest breaks, safety labels, hand washing, weather checks, gear inspection, and debriefs

- Create an environment characterized by good psychological safety, where people are included, treated equitably, welcomed and accepted for who they are

- Establish a Just Culture where workers are appreciated for reporting safety incidents, and are not inappropriately punished for making errors or documenting mistakes

The American Industrial Hygiene Association, a non-governmental workplace safety body, reminds of the limitations of administrative measures: “With administrative controls, the hazard itself is not actually removed or reduced, and risk reduction for the worker is dependent on the worker following the required work practices.”

Protect people with PPE

- Ensure backpacking program participants have high-quality hiking boots with good traction and ankle support

- Ensure climbing helmets are intact and properly fitting

- Use parasols (sun umbrellas) to provide shade when hiking in hot and humid conditions

- Install hand lines in challenging terrain

- Ensure raingear is fit for purpose

When a safety concern arises, some organizations are quick to provide PPE to their employees, or add to a procedure or checklist, or include the safety concern in a training, and then proceed to assume that that’s enough.

Organizations may be tempted to take administrative and PPE-centric measures, as they are relatively easy to take, and have little upfront expense. However, these measures are less effective in the long run. In addition, quantitative research suggests that in some contexts a focus on managing risk by issuing PPE may be more expensive over the long term.

SafeWork NSW, the workplace health and safety regulatory authority in New South Wales, Australia, notes that using PPE is “the least effective way to manage risks.”

Similarly, the Department of Environment and Conservation of the Government of Western Australia calls the use of PPE “the last resort.” The agency says, “This is the least preferred option and should be considered only when other control measures are not practicable, or to increase protection.”

The reason that use of PPE is the least effective method for protecting an individual from hazards is that the risk is not eliminated, and the PPE may be inadequate or may fail.

PPE can even have negative effects. For example, during a “swim test” of a program participant at an outdoor education center in Minnesota USA, a participant sank. Rescue boaters attempted to rescue the participant by diving to the lake bed, but were hindered by the PFDs they were wearing. The participant drowned.

History and Evolution of the Hierarchy of Controls

People have been prioritizing risk management actions for thousands of years.

The Hierarchy of Controls model, however, was introduced by the National Safety Council in the USA in the 1950s.

In the following decades, the HoC has been adopted by workplace health and safety authorities around the world, and incorporated into health and safety regulations.

The HoC is used in many industries, from manufacturing to outdoor recreation, adventure tourism, and adventure-based learning.

For example, Outward Bound Australia has for many years included the Hierarchy of Controls in its safety practices; the familiar triangular HoC diagram is in the organization’s Operational Risk Management Policy document.

Variations of the Hierarchy of Controls

There are dozens of variations of the Hierarchy of Controls, and the concept and expression of the HoC is continually evolving.

Various health and safety entities, from Australia to the USA, have slightly different approaches to describing the Hierarchy of Controls.

While the HoC is often interpreted as focusing on reducing the risks of physical harms such as injury and illness, it has also been used to support psychological risk management.

The Hierarchy of Controls has been adapted into a “Total Worker Health” model by NIOSH. The Total Worker Health model addresses psychosocial safety and well-being, and includes components around designing environments for well-being, and education on health and well-being.

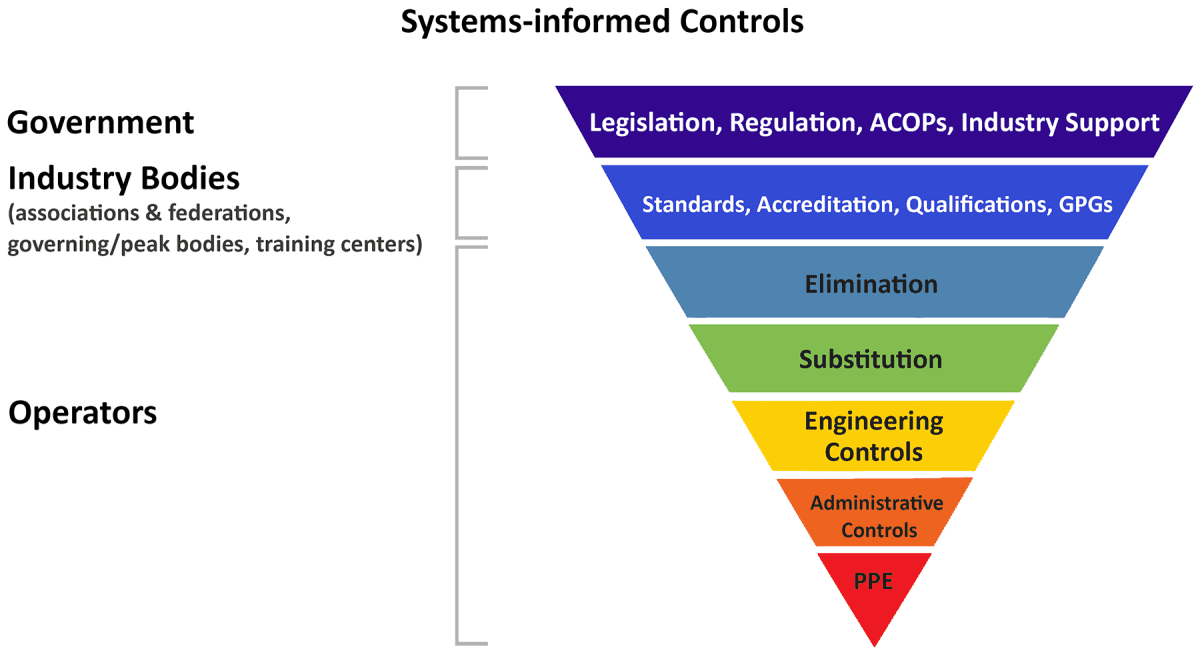

A Hierarchy of Controls Model Informed by Systems Thinking

The classic HoC is designed for use by companies, mostly to reduce risk to their workers. As such, it doesn’t fully consider the contributions of other entities outside of the company which can support good safety outcomes.

The AcciMap model and Risk Domains model of risk management, informed by the contributions of complex sociotechnical systems theory to understanding incident causation and prevention, recognize that government bodies and industry associations can contribute to the quality of risk management in any business or undertaking.

A risk management model that incorporates systems thinking recognizes that:

- Governments can support good safety outcomes by passing and appropriately enforcing safety law and regulations, developing activity-specific Approved Codes of Practices, and providing financial and logistical support for private industry to develop safety standards, training schemes, and other supports for good risk management.

- Industry bodies such as activity-specific associations, federations and unions of associations, National Governing Bodies (peak bodies) and training centres can develop safety and quality standards, organizational accreditation schemes, individual practitioner certification (qualification) schemes, and extensive Good Practice Guides providing detailed information about good safety procedures.

When outdoor and adventure operators, industry bodies and government entities cooperate, participants on trips, excursions and experiential adventures have the best probability of experiencing good safety outcomes.

Considerations Around the Hierarchy of Controls

HoC Is for Workers and Customers

The classic emphasis of the Hierarchy of Controls is reducing risk to workers in the occupational context. Outdoor adventure, recreation and experiential education organizations, however, have a heavy focus on safety of participants. In these contexts, the HoC can—and should—be applied to participant safety.

HoC and Approaches for Managing Risk

Some safety-minded professionals may recall that four general approaches to managing risk are recognized:

- Eliminate

- Reduce

- Transfer

- Accept

The Hierarchy of Controls is compatible with this four-part classification of risk management strategies. The two classification schemes, which partially overlap, each have a contribution to make to the design of comprehensive, effective risk management plans.

Is “Manage” More Appropriate than “Control?”

Some safety specialists who have an appreciation for managing risks in complex systems—such as led outdoor activities and adventurous excursions—recognize that it is not possible to identify, prioritize and completely control all hazards and risks that exist in a complex sociotechnical system.

In addition, it isn’t always possible to control sources of risk, such as human behavior, the function of equipment, whether or not safety procedures are followed, and environmental conditions.

In light of this, these risk management professionals may prefer to use the term “risk management” over “risk control.”

Nevertheless, “control” is commonly employed by health and safety authorities in describing the Hierarchy of Controls, and so, to support clarity, the term “control” is also used here.

Use the Hierarchy of Controls Before An Incident—Or After

Control measures can be used to prevent an incident from occurring in the first place. They can also be employed to minimize the harm from an incident that has already come to pass.

Examples of the use of Hierarchy of Controls measures to reduce the likelihood or severity of an incident include:

- Operational area selection

- Activity selection

- Route selection

- Medical screening

- Establishment of minimum staff qualifications/capacities

- Vendor (provider, supplier) selection

- Accreditation

- Equipment management

- Risk communication in promotional materials

Examples of the use of Hierarchy of Controls measures to mitigate the harms from an incident that has already occurred include:

- Emergency response planning

- First aid and rescue training

- Insurance

- Media relations strategy

A Tool Is Only Useful if Applied Properly

The Hierarchy of Controls is one tool that individuals can use to reduce the probability and magnitude of harms.

It is but one tool among many, however, and its effectiveness depends on how it is used, by whom, and when.

The HoC is most effective when used with other instruments for reducing risk.

Engineering Controls and Outdoor Safety: A Mountain Tragedy

In November of 2021, maintenance workers shut down an Austrian mountain hut for the winter. They sealed off the ventilation pipes from the hut’s stove for the season.

That winter, Dave Ayers, 36, a British ski instructor working in Brand, a municipality in Austria’s mountain region of Vorarlberg, entered the hut. Apparently unaware the stove’s flue was blocked, he lit a fire to get warm. The carbon monoxide fumes from the fire asphyxiated him, it is believed, and his frozen body was found in the hut that January.

What engineering controls could have been put in place by facility mangers so that Dave—remembered fondly as a warm-hearted, kind and humorous soul—might not have perished?

Avoiding Person-Centric Controls

A central lesson in the Hierarchy of Controls is that the most effective controls do not depend on the action or judgment of a person. Instead, the best safety controls are the ones that eliminate, reduce, or separate risks from people, without requiring decisions, vigilance or good decision-making.

The Hierarchy of Controls helps us understand the many entities that are involved in preventing harms—from government regulators who establish safety requirements, to industry associations who establish safety standards, to the administrators of outdoor and adventure experiences who design and manage travel, excursion, wilderness and experiential programs.

The Hierarchy of Controls makes clear that depending on the actions of workers is the least effective measure of control, and that other safety measures should instead be prioritized.

A popular mountaineering manual stated, “Climbers themselves are responsible for nearly all climbing accidents.” However, we can recognize that the best and most current thinking about incident prevention does not support this assertion.

Research on incident causation suggests that person-centric controls are considered weak.

Instead, serious incidents generally arise from a combination of risk factors in risk domains involving government, outdoor industry associations, and management decisions made by administrators of organizations that provide or coordinate outdoor experiences, as well as the actions of field leaders.

Blaming activity leaders and field personnel for causing an incident, when the most potent contributing factors are actually outside of their control, can lead to psychological harm, and is not optimally effective in identifying and addressing the underlying factors that led to a safety incident.

Where the Hierarchy of Controls is Required

In general, businesses have a duty to take reasonable precautions to prevent reasonably foreseeable harms. However, the Hierarchy of Controls is not explicitly written into many health and safety acts or regulations.

There are, however, in recognition of the power and value of the HoC, two cases in the outdoor and adventure sector where application of the Hierarchy of Controls is compulsory.

Use of the Hierarchy of Controls is required for adventure activity providers seeking to achieve accredited status through the Viristar Adventure Safety Accreditation scheme. Accreditation Standard SM.02 is “The safety management system employs a hierarchy of controls.” Additional requirements under that standard are specified by Elements of Performance under Standard SM.02.

In addition, use of the Hierarchy of Controls is required of adventure activity operators in New Zealand by sub-section 4.2 of the Safety Audit Standard, under the Health and Safety at Work (Adventure Activities) Regulations 2016, under New Zealand’s Health and Safety at Work Act.

The Safety Audit Standard language states:

The operator must eliminate serious risks arising from their activities, so far as is reasonably practicable.

When it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate serious risks, the operator must minimize the serious risks arising from their activities.

In minimizing risks, the operator must (if reasonably practicable) take one or more of the following actions that is most appropriate for the risk:

- Substituting the hazard giving rise to the risk with something that gives rise to a lesser risk

- Isolating the hazard giving rise to the risk to prevent anyone coming into contact with it

- Implementing engineering controls.

The operator must manage the remaining risk arising from their activities, by using the administrative controls and/or PPE that are most appropriate for the risk.

Conclusion

Emily Jordan was described as a talented and intelligent young person who enjoyed having fun, but who did not take unnecessary risks.

The adventure activities operator running the riverboarding excursion where Emily drowned pleaded guilty to two charges of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure the safety of their customers, employees and other clients, brought under the Health and Safety in Employment Act. The operator was fined $66,000 and ordered to pay $80,000 in reparations to Emily’s family.

After the riverboarding tragedy—and, two weeks later, the death of six students and their teacher in a flooded New Zealand canyon, Mangatepopo Gorge—the New Zealand government passed adventure safety regulations.

These regulations require certain adventure operators in New Zealand to use the Hierarchy of Controls to manage risk, implement Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for activities, ensure staff are competent, ensure that appropriate quantities of suitable equipment are followed, have an emergency response plan, review and follow up on incidents, and engage in continuous improvement, among other steps.

The dedication of Emily’s family to see that other adventure activity participants could safely enjoy fun and thrilling outdoor experiences led to a complete overhaul of New Zealand’s adventure sector, helping position it as one of the most well-managed and high-quality adventure destinations globally, and a role model for adventure travel and outdoor experience providers around the world.